Photosynthesis is quite the catalyst for life, yet it’s easy to overlook this humble chemical process. But what if you could see its results scaled across the globe?

The Pulse of Nature

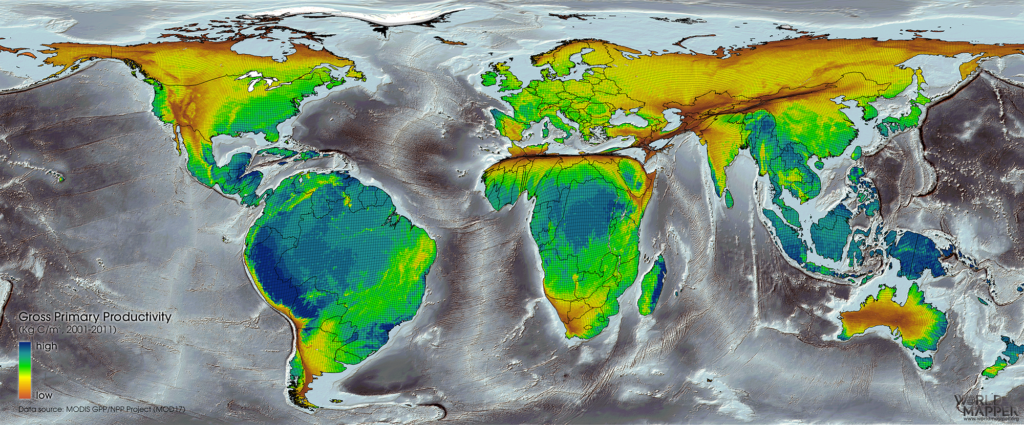

Today’s unique cartogram animation comes from geographer Benjamin Hennig at Worldmapper, and it depicts ongoing cycles in the productivity of ecological systems around the world. Created with Yadvinder Malhi from the University of Oxford, the researchers factored the daily net photosynthesis value over an 8-day interval of satellite observations, and extrapolated the trends for a year. The outcome? A pattern of gross primary productivity (GPP) – the net amount of energy produced by land plants during photosynthesis – resembling the rhythmic impression of a “heartbeat”. Here’s how a big-picture of average annual productivity ends up looking:

Location, Location, Location

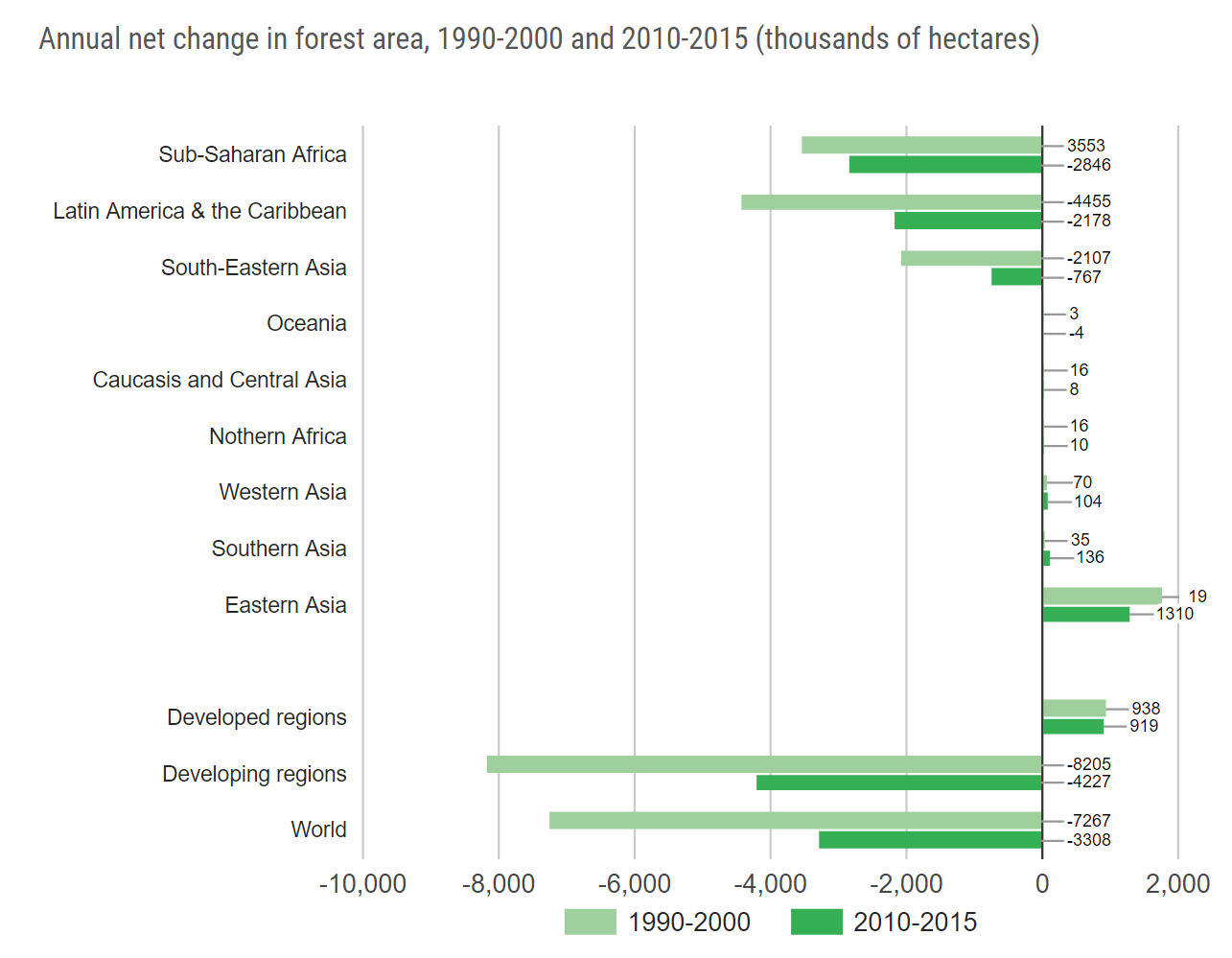

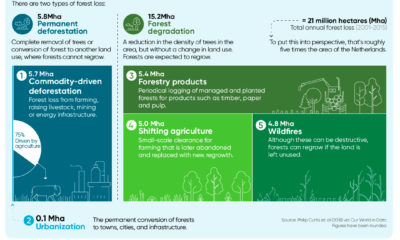

Although the entire biosphere harnesses the sun’s energy, it’s clear this varies greatly based on both region and season. For example, desert areas such as the Sahara or Australian Outback occupy relatively low productivity areas on the map. The taiga biome, a boreal forest made of coniferous trees such as pines, accounts for nearly a third of the world’s forest cover. Since the largest boreal areas are in Russia and Canada, it’s no wonder their productivity shrinks dramatically when it gets a bit cooler up north. When these areas slow down in sub-zero temperatures, their tropical neighbors to the south do the heavy lifting. It’s also why rapid deforestation of these areas is cause for alarm. Many environmental scientists suggest that our human impact on forests could intensify global warming. But there is good news – since the 1990s, the rate of net forest loss has declined by almost half. Progress fares differently across the regions: Image Source: United Nations on Aside from the obvious climate impact they bring, one other downside in particular is spills, which can lead to ecological and economic damage. These can happen due to pipeline leaks, train derailments, or other industrial disasters. This graphic from Preyash Shah provides a visual overview of every oil and gas spill in the contiguous U.S. since 2010. Data is tracked by the U.S. government’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA).

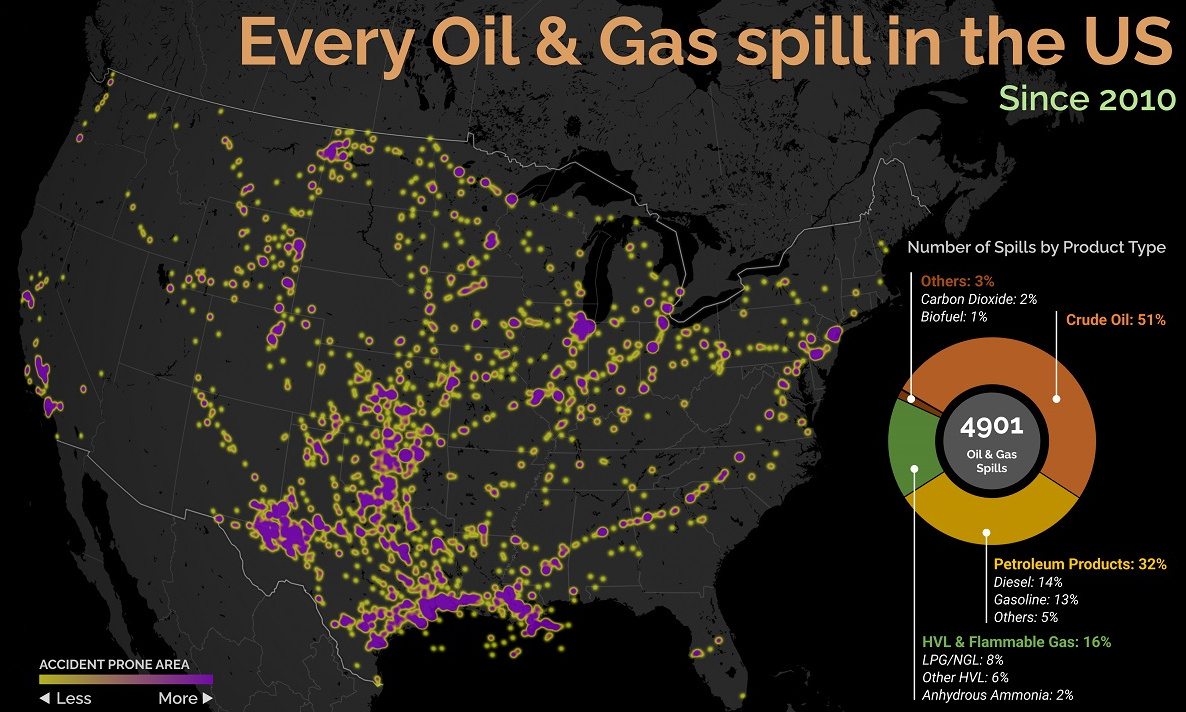

U.S. Oil and Gas Spills (2010‒2022)

The majority of spills that have occurred come mostly from crude oil, followed by petroleum products and gas. Note that this data covers the quantity of spills and not damages or volume.

Crude oil, which makes up just over half of documented spills, is also one of the most costly. Contaminations can persist for years after a spill, and its impact on local mammals and waterfowl is particularly harsh. This has been the case with the Deepwater Horizon spill (also known as the “BP oil spill”), which experts say is still causing harm in the Gulf of Mexico. Other products with lots of spills include petroleum products such as diesel or gasoline, as well as liquefied natural gas or other volatile liquids. Interestingly, liquefied carbon dioxide can also be transported in pipelines, commonly used for carbon capture storage, but requires high pressure to maintain its state. When looking at the location of spills, it’s clear that the South Central states have experienced the highest number of disasters. In contrast, the West Coast has had substantially less activity. However, this makes much more sense when looking at the dominant oil producing states, where Texas and surrounding neighbors reign supreme. Of the 4,901 spills during this period, Texas accounts for 1,936 or roughly 40% of all oil and gas spills. This is followed by Oklahoma, which has had 407 spills and is one of the largest net exporters of oil and gas in the country.

What Causes Spills?

Oil and gas spills actually have a surprisingly long history, with one of the earliest dating back to 1889, when a spill was reported on the coast between Los Angeles and San Diego. Causes have consisted primarily of weather, natural disasters, equipment and technological malfunction, as well as human error. However, they only became a widespread problem around the halfway mark of the 20th century, when petroleum extraction and production really began to take off. This era also saw the emergence of supertankers, which can transport half a million tons of oil but therefore make the risk of spills even costlier. In fact, the biggest spill off U.S. waters after the Deepwater Horizon disaster is the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska, when a tanker crashed into a reef and 11 million gallons of oil spilled into the Pacific Ocean.