Aside from their massive populations and geographical proximity in Asia, the two nations also have deep cultural histories and traditions, growing amounts of influence on the world stage, and burgeoning middle classes. China and India combine to be home to one-third of the world’s megacities, and they even had identical real GDP growth rates of 6.1% in 2019, based on early estimates by the IMF.

Diverging Demographics

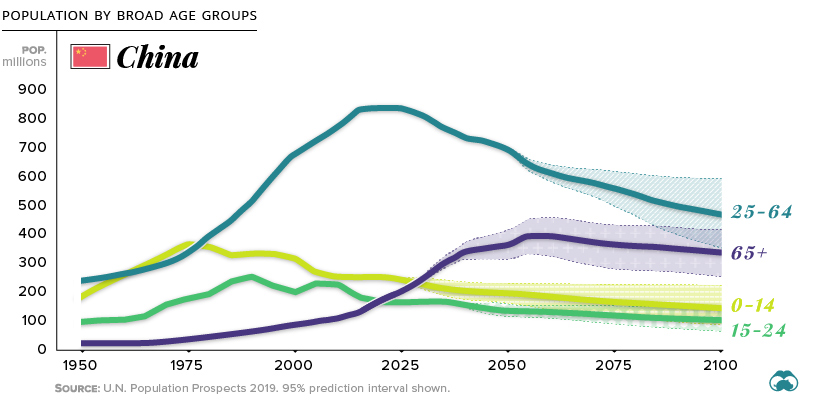

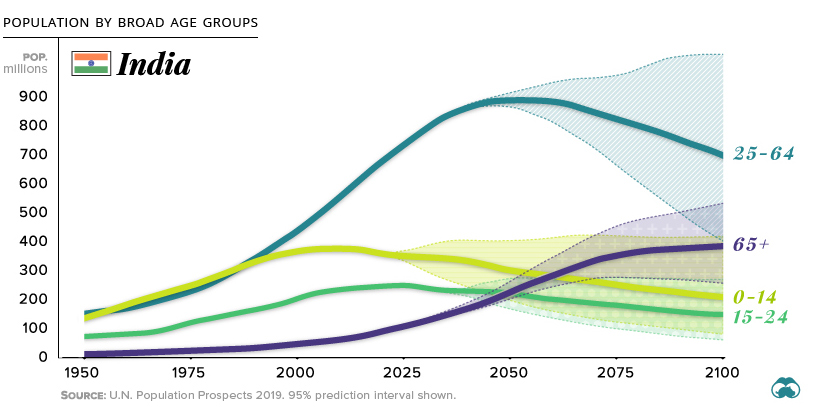

But aside from the obvious differences in their political regimes, the two populous nations have also diverged in another way: demographics. As seen in today’s animation, which comes from AnimateData and leverages data from the United Nations, the two countries are expected to have very different demographic compositions over time as their populations age. The easiest way to see this is through a macro lens: Populations of China and India (1950-2100) Although the countries have roughly the same populations today — by 2050, India will add roughly 270 million more citizens, and China’s total will actually decrease by 30 million people. Let’s look at the demographic profiles of these countries to break things down further. We’ll do this by charting populations of age groups (0-14 years, 15-24 years, 25-64 years, and 65+ years).

China: Aftermath of the One-Child Policy

China’s one-child policy was implemented in 1979 — and although it became no longer effective starting in 2016, there’s no doubt that the long-term demographic impacts of this drastic measure will be felt for generations:

The first thing you’ll notice in the above chart is that China’s main working age population cohort (25-64 years) has essentially already peaked in size. Further, you’ll notice that the populations of children (0-14 years) and young adults (15-24 years) have both been on the decline for decades.

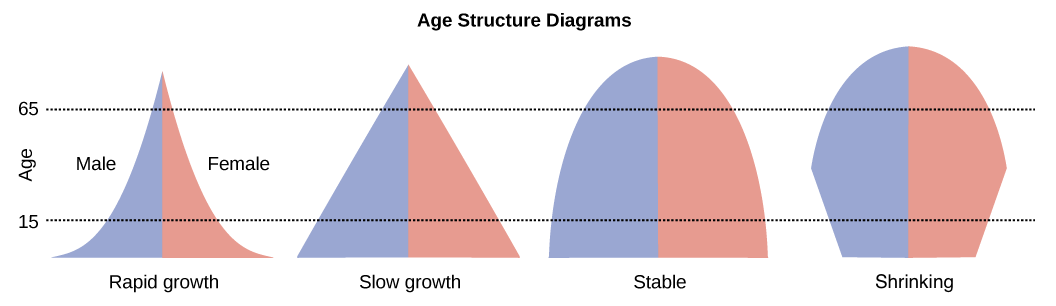

A reduction in births is something that happens naturally in a demographic transition. As an economy becomes more developed, it’s common for fertility rates to decrease — but in China’s case, it has happened prematurely through policy. As a result, the country’s age distribution doesn’t really fit a typical profile.

India: A Workforce Peaking in 2050

Meanwhile, projections have India reaching a peak workforce age population near the year 2050:

By the year 2050, it’s estimated that India’s workforce age population will be comparable in size to that of China’s today — over 800 million people strong. However, given that this is at least 30 years in the future, it raises all kinds of questions around the economic relevance of a “working age” population in a landscape potentially dominated by technologies such as artificial intelligence and automation.

Different Paths

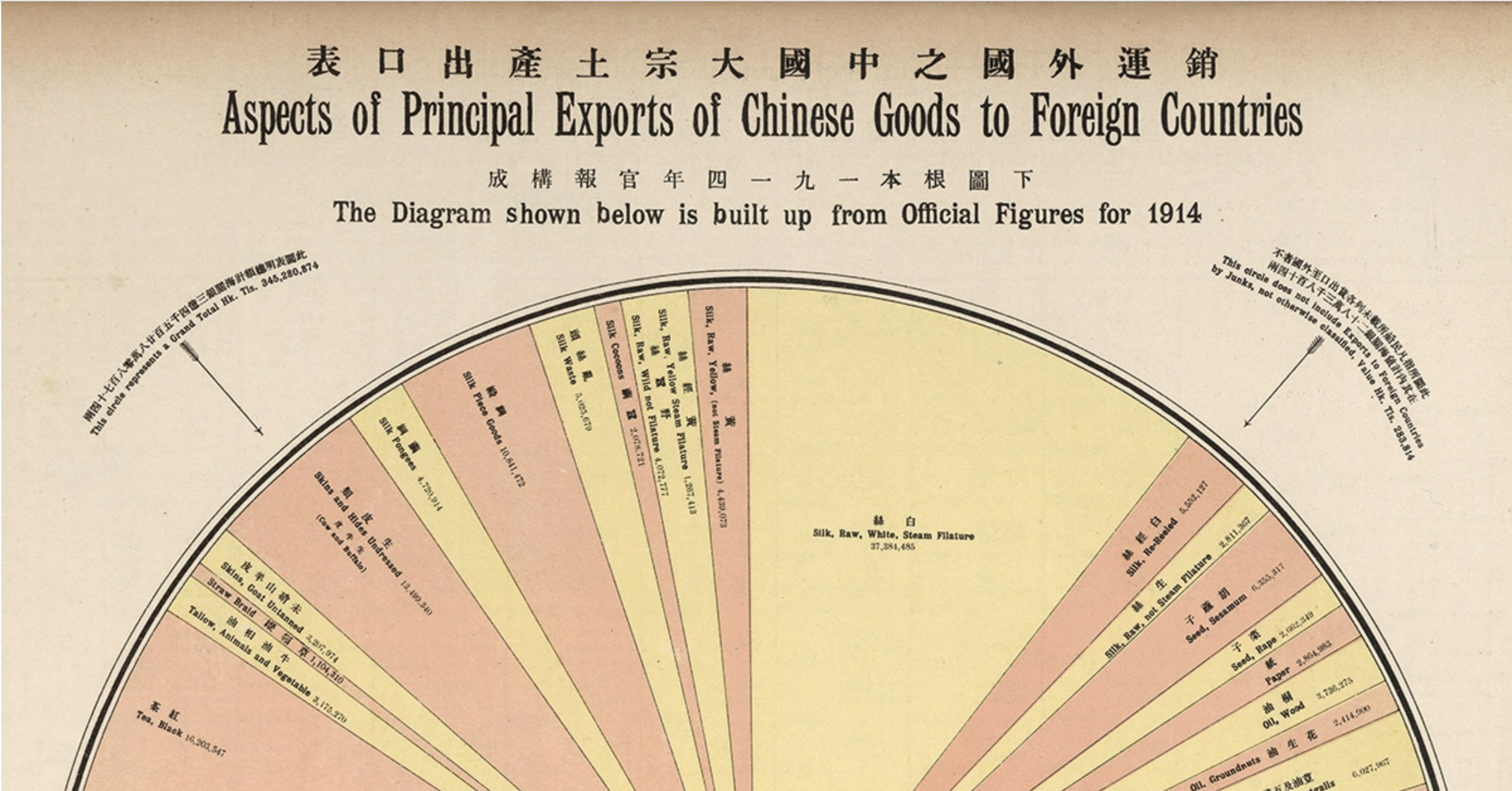

While it’s clear that the world’s two most populous countries have some key similarities, they are both on very different demographic paths at the moment. China’s population has plateaued, and will eventually decline over the remainder of the 21st century. There is plenty of room to grow economically, but the weight of an aging population will create additional social and economic pressures. By 2050, it’s estimated that over one-third of the country will be 60 years or older. On the other hand, India is following a more traditional demographic path, as long as it is uninterrupted by drastic policy decisions. The country will likely top out at 1.6-1.7 billion people, before it begins to experience the typical demographic transition already experienced by more developed economies in North America, Europe, and Japan. And by the time the Indian workforce age group hits 800+ million people, it will be interesting to see how things interplay with the world’s inevitable technological shift to automation and a changing role for labor. on A statement that is as profound as it is banal. In other words, when we do history, we’re a bit like tourists. If we really want to understand the past, we have to think like a local. The infographic above, Aspects of Principal Exports of Chinese Goods to Foreign Countries, is the first in a series that we’re calling Vintage Viz, which presents a historical visualization along with the background and analytical tools to make sense of it. Today, the People’s Republic of China is the second largest economy in the world, a permanent member of the UN Security Council, and a growing military power. But at the dawn of the 20th century, things were much, much different.

Opium and the Opening of China to the West

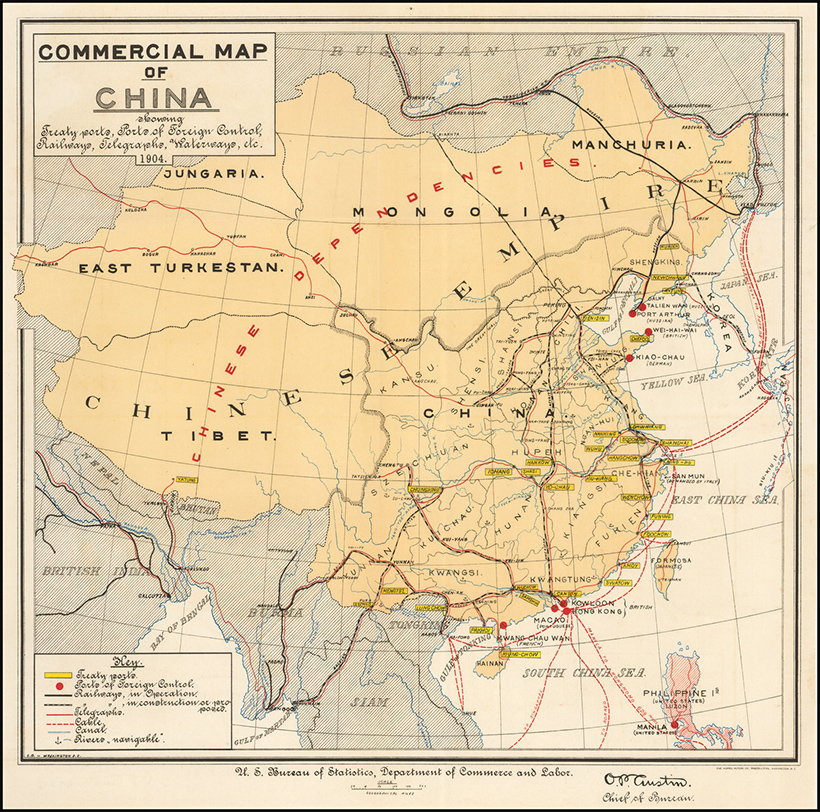

Early Sino-Western trade was restricted by the Qing emperors to three ports, and after 1757, just one, in what became known as the Canton System. This name came from the one remaining port city of the same name, present-day Guangzhou. Foreign trade was tightly monitored and subject to stiff tariffs, and Western traders chafed under these restrictions. So when in 1839, Chinese authorities moved to shut down opium smuggling—an important source of profit for foreign merchants—Western powers saw their chance and used the pretext to revise the terms of trade by force. In what became known as the Opium Wars, 1839-1842 and 1856-1860, first Great Britain and then an Anglo-French alliance defeated imperial China and imposed punitive treaties that included indemnities and lowered tariffs, but also expanded the number of ports open to foreign traders, first to five and by 1911, to more than 50.

Westerners were exempted from local laws, Christian missionaries were allowed to proselytize freely, and the opium trade was legalized. Hong Kong was also ceded to Great Britain at this time. The Treaty Port Era, also known as the Century of Humiliation, was perhaps too much for the country to bear. The weakened central government was beset by popular unrest, including the Taiping Rebellion (1850–64), which killed 20 million people, and the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901), so-named for the secret society that led the movement, the Righteous and Harmonious Fists. Eventually, the last Chinese emperor was deposed and a republic declared in 1911. Nevertheless, the government was too weak to impose its will, and was repeatedly challenged by warlords. So as we approach the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, and the period covered by our visualization, we find China weakened internally by civil strife, and externally by Western powers.

The History of this Century-Old Pie Chart

Aspects of Principal Exports of Chinese Goods to Foreign Countries captures Chinese exports for 1914, and comes from The New Atlas and Commercial Gazetteer of China: A Work Devoted to Its Geography & Resources and Economic & Commercial Development. Originally published in 1917 and edited by Edwin J. Dingle for the Far Eastern Geographical Establishment, the volume contains a wealth of data for the period. According to the book’s Preface, it “seeks to give all the information that is essential to the business-man in regard to a country… about which less is known than in regard to any similar area in the world.” The visualization breaks down total Chinese exports for 1914 in haikwan taels (hk. tls.), a unit of silver currency used to collect tariffs. In 1907, one haikwan tael was worth $0.79 U.S. dollars. Official figures come from the Chinese Maritime Customs Service. This was set up by foreign consuls after the First Opium War to collect tariffs to guarantee the payment of treaty indemnities. Exports in 1914 represented 345 million hk. tls., a 14.4% decrease from 1913, likely owing to the outbreak of the First World War that same year. Apart from “Other Metals and Minerals, Sundries, etc,” which served as a catch-all category, the largest categories were silks and teas of various types, representing 22.6% and 10.4% of total exports respectively. Below are some more details that emerge from this visualization.

All the Tea in China

The Chinese tea trade was the subject of another visualization in the Atlas. It shows that China had been steadily losing ground to British India. Between 1888-1892 Chinese exports to Great Britain were 242 million pounds against India’s 105 million pounds. By 1912-1913, India had surpassed China to export 279 million pounds against 198 million pounds. In 1914, the majority of Chinese exports went to Russia, 902,716 piculs in all. A picul is equal to “as much as a man can carry on a shoulder-pole” or about 133 pounds.

The Silk Road to Profits

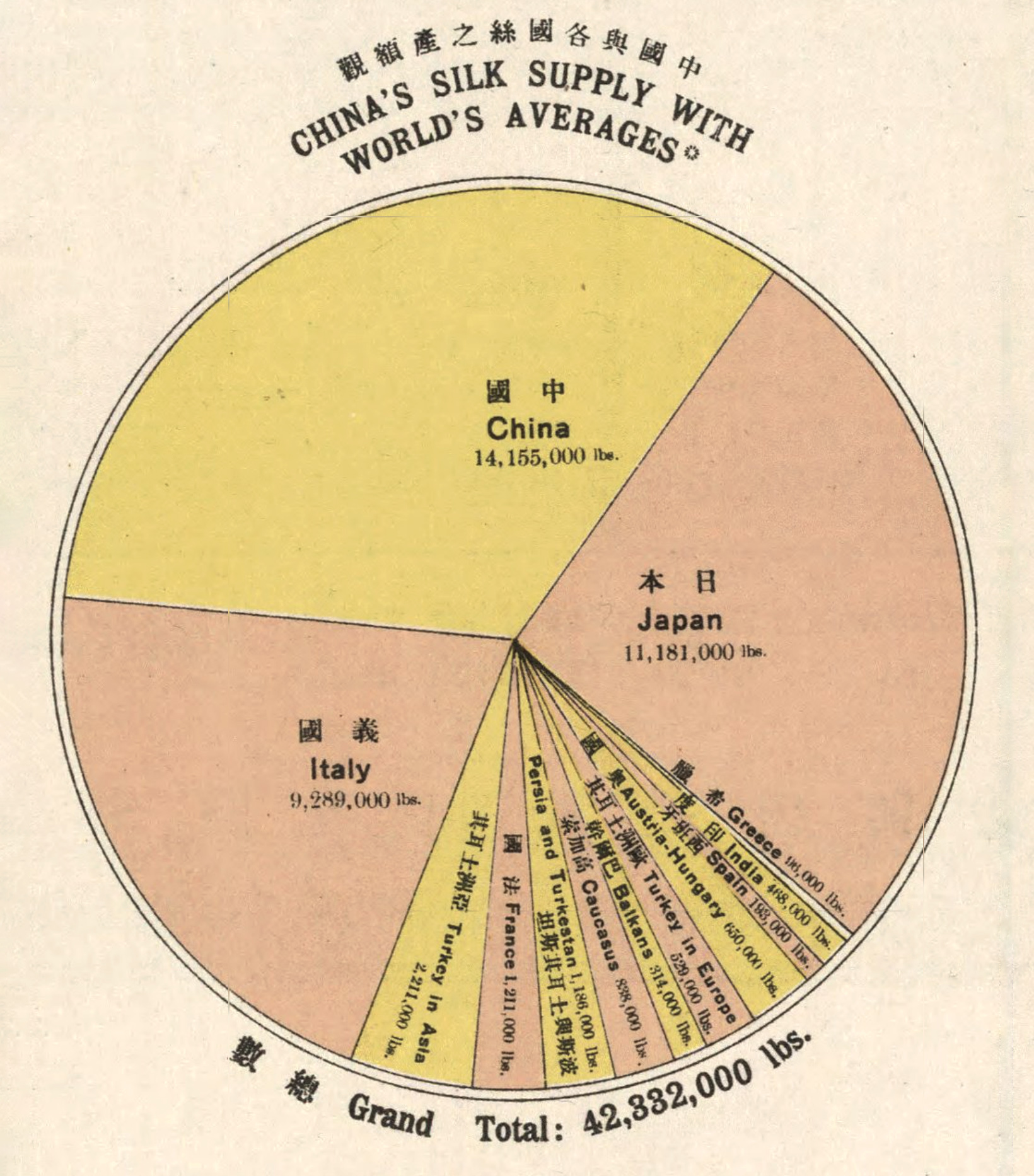

Silk has long been in demand in the West as a luxury good, giving its name to the overland trade route that connected East and West for centuries: the Silk Road. In 1914, China was the largest producer and exporter of silks in the world. On an annual basis, China averaged 14 million pounds, compared to the number two spot, Japan, at 11 million pounds, and number three, Italy, at 9 million pounds. Together, these three controlled 81.7% of the global silk trade.

The Opium of the Masses?

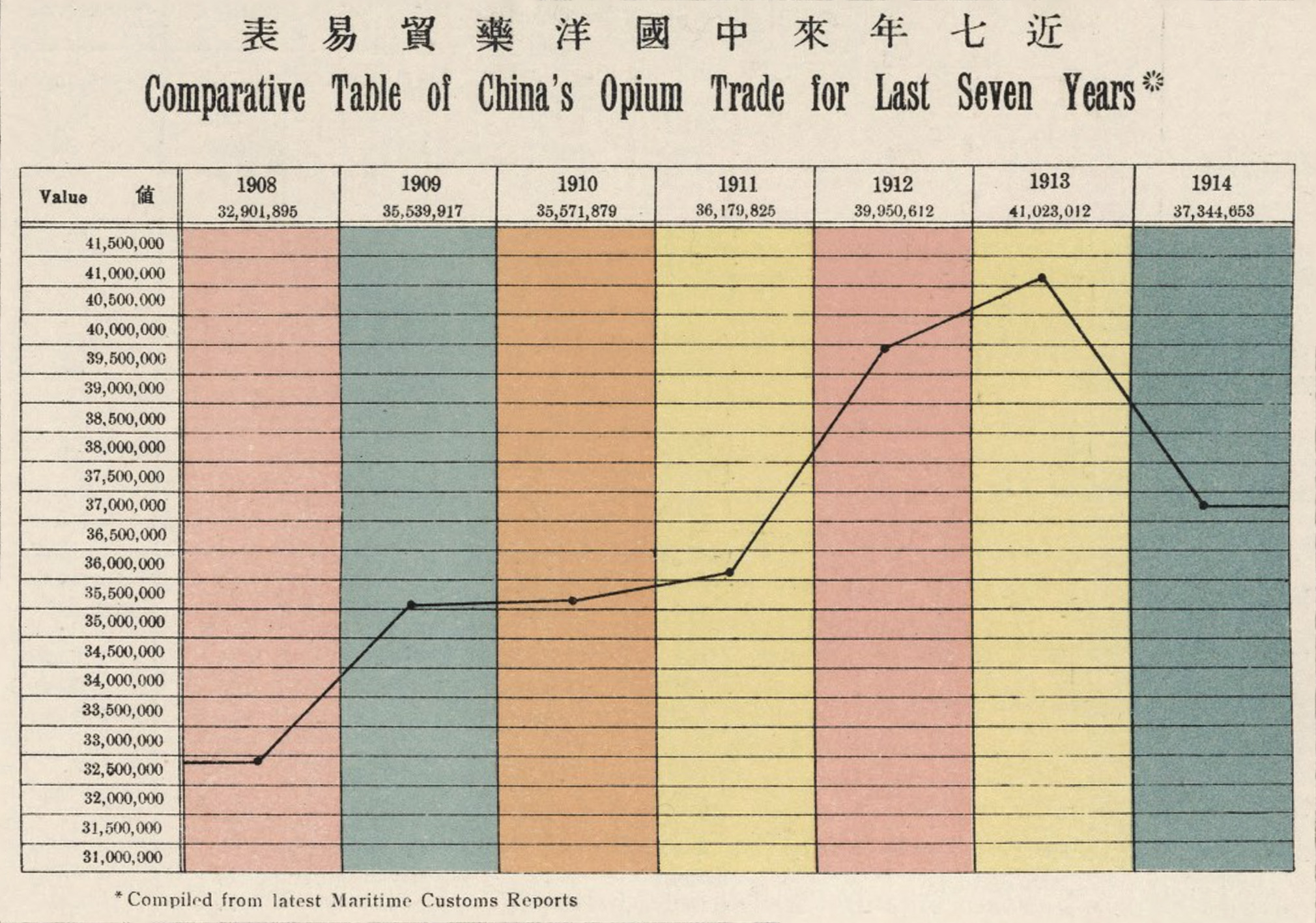

The opium trade, the pretext that opened China to foreign trade, was still big money in 1914. A total of 37 million hk. tls. were imported in 1914 from India, up 11.9% from 1908. This is actually down from a peak of 41 million hk. tls. in 1913.

In 1907, China signed the Ten Year Agreement with India, which ultimately phased out the opium trade. By 1917 the trade was all but extinguished.

Back to the Future

The Aspects of Principal Exports of Chinese Goods to Foreign Countries is a far cry from the contemporary trade picture. China’s top export in 2021 was in the category “telephones for cellular networks or other wireless networks,” and was worth $147.1 billion. But it’s worth noting that China today is a direct result of this period. The resentment created during the Century of Humiliation would eventually help lead to Mao Zedong, the Long March, and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. And in 1979, the Chinese central government would set up the first of their own “treaty ports,” in the form of special economic zones, places where foreign companies could set up shop. But this time, it wasn’t foreign powers who were making the rules.