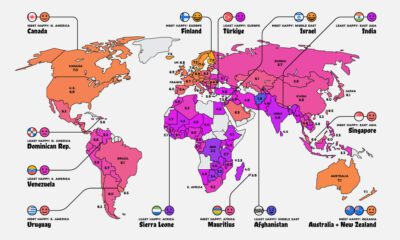

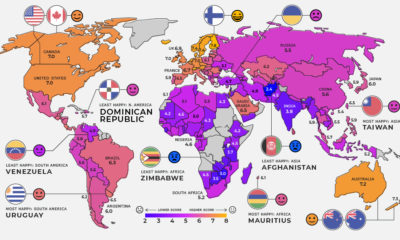

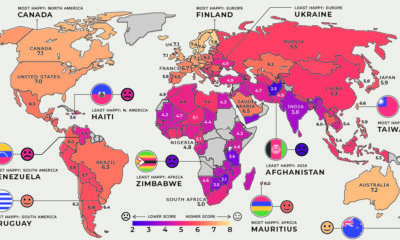

Is it reasonable then, in our quest for happiness, to begin working less? Advocates of a shorter workweek would agree, but these policies have yet to be widely-adopted. Today’s chart plots data from the World Happiness Report 2019 and the OECD to determine if there’s any correlation between a country’s happiness and average hours worked per person.

What Happens When We Work Too Much?

The unhealthy side effects of working long hours are well established. In extreme cases, however, symptoms can extend beyond the usual stress and fatigue. For example, the American Heart Association found that people under the age of 50 had a higher risk of stroke when working over 10 hours a day for a decade or more. Another study, conducted across 14 countries, concluded that people who worked long hours were 12% more likely to become excessive drinkers. If working longer days is so harmful to our well-being, what happens if we work fewer hours instead?

Comparing the Numbers

The tables below list the happiest countries as well as the unhappiest countries in the OECD; happiness scores range from 0 to 10, with a 10 representing the best life possible. Based on the data, there appears to be some degree of correlation between a person’s happiness and the amount of hours they work. Here’s how the five happiest countries stack up: The five happiest countries each work over 100 hours less than the OECD average. Compare this to the five least happiest countries:

Coincidentally, all five of the least happiest countries work more hours than the OECD average, up to over 264 hours in the case of Greece. Happiness is multifaceted, though, and we should avoid drawing conclusions from a single variable. For instance, the World Happiness Report 2019 calculates happiness scores based on eight distinct metrics: With these in mind, we can make a few additional observations. Four of the five happiest OECD countries are located in the Nordics, a region known for low corruption rates and robust social safety nets. On the other end of the scale, economic hardship is a recurring theme among the OECD’s least happiest countries. The falling Turkish lira and Greece’s debt crisis are two significant examples. To properly measure the happiness-boosting potential of a shortened workweek, it seems we need to isolate its effects.

Challenging the Status Quo

Employers are now experimenting with shorter work schedules to see if happier employees are in fact better employees.

Case 1: Successful Trial

Perpetual Guardian, a New Zealand-based estate planning firm, trialed a four-day workweek for two months with no changes to compensation. The trial was hailed as a success. Employee stress levels fell by 7 percentage points while overall life satisfaction rose by 5 percentage points. Perhaps most impressive is the fact that productivity remained the same. – Helen Delaney, University of Auckland Following the trial, the firm’s founder expressed interest in implementing the four-day workweek on a permanent basis.

Case 2: Successful Trial with Trade-offs

Filimundus, a Sweden-based software studio, trialed a six-hour workday in 2014. Staff reception was positive, and the company has since adopted it permanently. There were trade-offs, however. While staff enjoyed more time for their private lives, productivity across different departments saw mixed results. – Linus Feldt, CEO Interestingly, the studio also trialed a seven-hour workday, and saw no positive effects.

Case 3: An Unsustainable Solution

Public healthcare workers in Gothenburg, Sweden, trialed a six-hour workday for two years. Similar to the first case, compensation was unchanged. While the trial achieved good results—staff experienced lower stress levels and patients received a higher level of care—the policy was unsustainable. – Daniel Bernmar 17 additional staff were hired to compensate for the shorter workdays, increasing the local government’s payroll by $738,000. The city council did note, however, that lower unemployment costs offset this increase by approximately 10%.

Picking Up Momentum

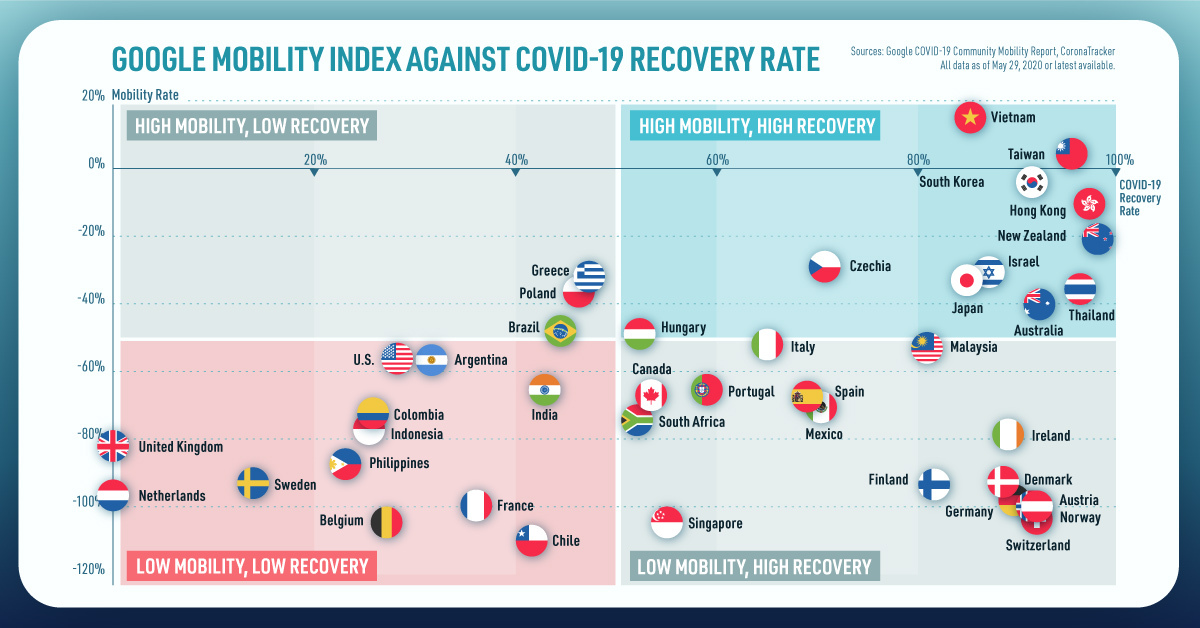

These experiments are garnering attention from around the world. Even Japan, a country known for its “overtime culture”, is getting in on the action. Microsoft offices in the East Asian country tested a four-day workweek in August 2019, and reported happier staff, as well as an impressive 40% boost in productivity. While the results of these early experiments are indeed promising, they’ve exposed the nuances that exist between industries and job types, and the need for further trials. One thing is certain though—shorter workweek policies should not be interpreted as a “one size fits all” solution for happier lives. on Today’s chart measures the extent to which 41 major economies are reopening, by plotting two metrics for each country: the mobility rate and the COVID-19 recovery rate: Data for the first measure comes from Google’s COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports, which relies on aggregated, anonymous location history data from individuals. Note that China does not show up in the graphic as the government bans Google services. COVID-19 recovery rates rely on values from CoronaTracker, using aggregated information from multiple global and governmental databases such as WHO and CDC.

Reopening Economies, One Step at a Time

In general, the higher the mobility rate, the more economic activity this signifies. In most cases, mobility rate also correlates with a higher rate of recovered people in the population. Here’s how these countries fare based on the above metrics. Mobility data as of May 21, 2020 (Latest available). COVID-19 case data as of May 29, 2020. In the main scatterplot visualization, we’ve taken things a step further, assigning these countries into four distinct quadrants:

1. High Mobility, High Recovery

High recovery rates are resulting in lifted restrictions for countries in this quadrant, and people are steadily returning to work. New Zealand has earned praise for its early and effective pandemic response, allowing it to curtail the total number of cases. This has resulted in a 98% recovery rate, the highest of all countries. After almost 50 days of lockdown, the government is recommending a flexible four-day work week to boost the economy back up.

2. High Mobility, Low Recovery

Despite low COVID-19 related recoveries, mobility rates of countries in this quadrant remain higher than average. Some countries have loosened lockdown measures, while others did not have strict measures in place to begin with. Brazil is an interesting case study to consider here. After deferring lockdown decisions to state and local levels, the country is now averaging the highest number of daily cases out of any country. On May 28th, for example, the country had 24,151 new cases and 1,067 new deaths.

3. Low Mobility, High Recovery

Countries in this quadrant are playing it safe, and holding off on reopening their economies until the population has fully recovered. Italy, the once-epicenter for the crisis in Europe is understandably wary of cases rising back up to critical levels. As a result, it has opted to keep its activity to a minimum to try and boost the 65% recovery rate, even as it slowly emerges from over 10 weeks of lockdown.

4. Low Mobility, Low Recovery

Last but not least, people in these countries are cautiously remaining indoors as their governments continue to work on crisis response. With a low 0.05% recovery rate, the United Kingdom has no immediate plans to reopen. A two-week lag time in reporting discharged patients from NHS services may also be contributing to this low number. Although new cases are leveling off, the country has the highest coronavirus-caused death toll across Europe. The U.S. also sits in this quadrant with over 1.7 million cases and counting. Recently, some states have opted to ease restrictions on social and business activity, which could potentially result in case numbers climbing back up. Over in Sweden, a controversial herd immunity strategy meant that the country continued business as usual amid the rest of Europe’s heightened regulations. Sweden’s COVID-19 recovery rate sits at only 13.9%, and the country’s -93% mobility rate implies that people have been taking their own precautions.

COVID-19’s Impact on the Future

It’s important to note that a “second wave” of new cases could upend plans to reopen economies. As countries reckon with these competing risks of health and economic activity, there is no clear answer around the right path to take. COVID-19 is a catalyst for an entirely different future, but interestingly, it’s one that has been in the works for a while. —Carmen Reinhart, incoming Chief Economist for the World Bank Will there be any chance of returning to “normal” as we know it?