The economic situation, on the other hand, is unlikely to improve anytime soon. Falling revenues combined with costly pandemic relief measures have increased global debt by $20 trillion since the third quarter of 2019. By the end of 2020, economists expect global debt to reach $277 trillion, or 365% of world GDP. Today’s chart uses data from the Institute of International Finance (IIF) to provide an overview of where debt, relative to GDP, has increased the most.

Comparing Developed and Emerging Markets

Developed economies represent four of the five countries seeing the largest increases in debt-to-GDP, but looking from a more macro angle reveals that debt levels are rising at a similar pace around the world. Source: IIF, BIS, IMF, Haver, National Sources To put these figures into perspective, economists often use the debt-to-GDP metric, which compares a country’s debt to its economic output. As the name implies, it’s calculated by taking a country’s total debts and dividing them by its annual GDP. Having a low debt-to-GDP ratio suggests that a country will have little issues paying off its debts, while a high ratio can be interpreted as a sign of higher default risk. The actual definition of a “low” or “high” ratio is quite loose, though the World Bank believes there is a threshold for government debt at 77% of GDP. Every percentage point beyond this threshold has been found to detract 0.017 percentage points from annual growth.

Comparing Debt-to-GDP by Sector

To see how COVID-19 has affected the global economy since Q3 2019, let’s take a look at each sector’s debt as a percentage of GDP.

Within developed markets, government debt-to-GDP grew by 21 percentage points compared to 11 for non-financial corporates, and 6 for households. This is unsurprising as governments have supplied billions (or in some cases, trillions) of economic stimulus while also pulling in less tax revenue. The story in emerging markets is slightly different, with non-financial corporates experiencing the largest increase at 11 percentage points. The sector’s debt is now at 104% of GDP, making it the most highly-leveraged in the region.

Highlights from Today’s Chart

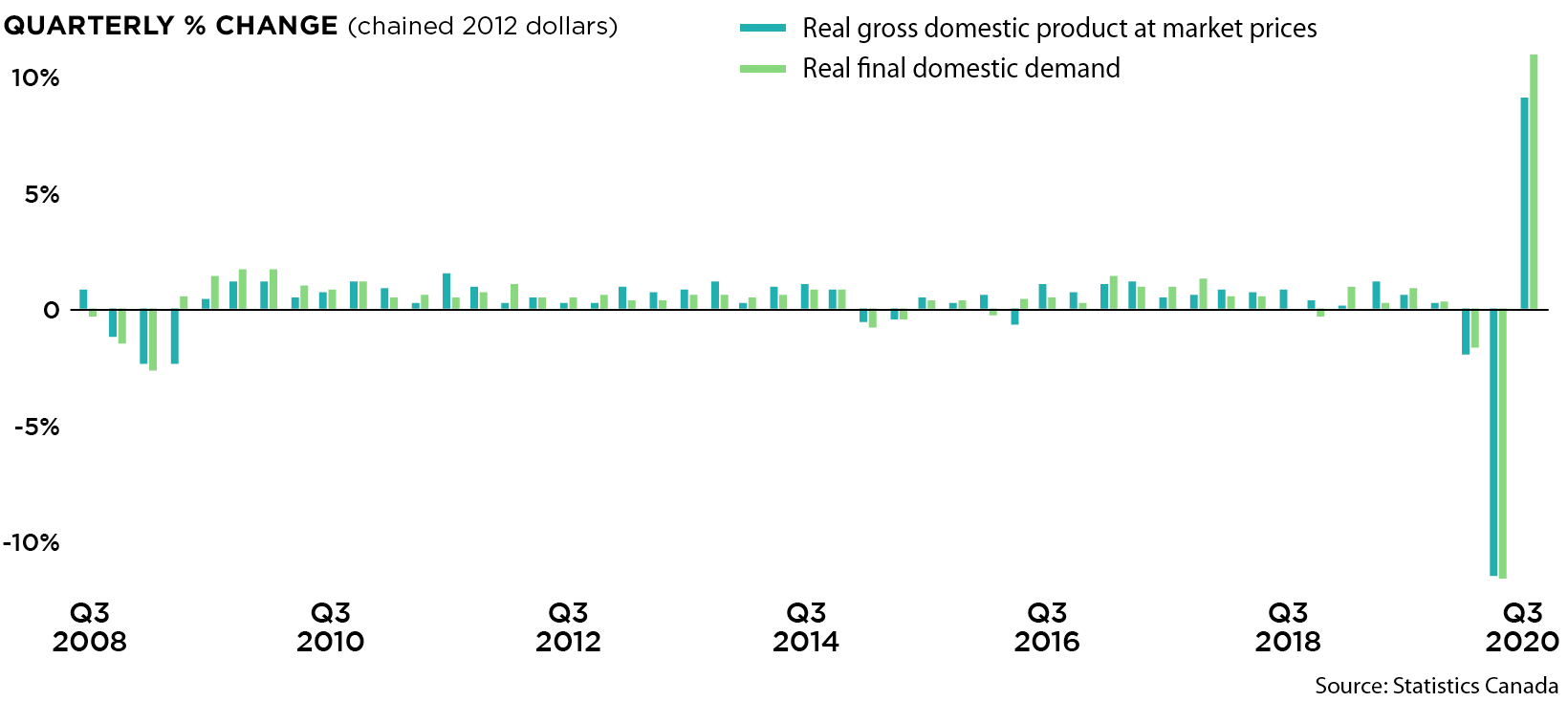

Today’s chart boils this data down to the individual country level, allowing us to identify two outliers: Canada and Australia. Excluding the financial sector, Canada’s debt-to-GDP ratio increased by nearly 80%, the highest of any developed country. Government borrowing surged as the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), which provided struggling Canadians with roughly $1,500 a month, rang up a bill of $60 billion over 7 months. An increase in debt wasn’t the only reason for the country’s worsening debt-to-GDP ratios. In Q2 2020, Canada’s GDP declined at an annualized rate of 38%, its worst three-month performance on record.

Australia was another outlier, but for a different reason; the country’s household debt decreased by almost 5% relative to GDP. This was likely due to an early-access scheme that allowed millions of Australians to make withdrawals from their superannuation, a social security fund similar to America’s 401(k). —Josh Frydenberg, Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Australia Officials have exercised caution around the prolonged use of these programs, as superannuation funds are meant to support people through retirement. Of the 2.6 million Australians that accessed their superannuations early, 500,000 are believed to have completely emptied their accounts.

Debt-to-GDP is Set to Fall…Or is it?

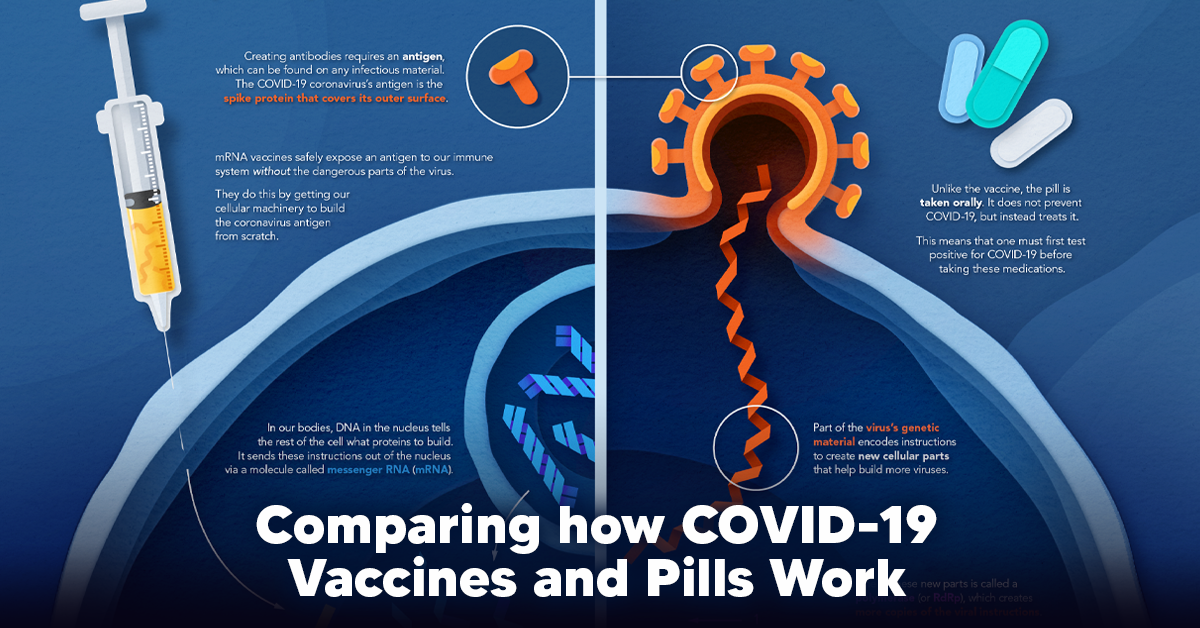

A global roll out of COVID-19 vaccines is likely to end the ongoing health crisis and allow the economy to return to pre-pandemic levels, though delays are to be expected. Regardless, this spells good news for governments and financial institutions around the world—economic output will recover, shrinking debt-to-GDP ratios. Whether or not borrowing will also slow down, however, is much harder to predict. Government borrowing has been relied on to stimulate growth since 2008, and with 75% of Americans in favor of a second COVID-19 relief bill, public debt is likely to accumulate further. Private sector debt is following a similar trend, with non-financial U.S. corporations owing $10.9 trillion as of Q2 2020, up from $6.4 trillion at the start of 2008. These growing debts have been manageable thanks to an extended period of low interest rates and loose monetary policy, but whether or not this is sustainable remains to be seen. on The leading options for preventing infection include social distancing, mask-wearing, and vaccination. They are still recommended during the upsurge of the coronavirus’s latest mutation, the Omicron variant. But in December 2021, The United States Food and Drug Administration (USDA) granted Emergency Use Authorization to two experimental pills for the treatment of new COVID-19 cases. These medications, one made by Pfizer and the other by Merck & Co., hope to contribute to the fight against the coronavirus and its variants. Alongside vaccinations, they may help to curb extreme cases of COVID-19 by reducing the need for hospitalization. Despite tackling the same disease, vaccines and pills work differently:

How a Vaccine Helps Prevent COVID-19

The main purpose of a vaccine is to prewarn the body of a potential COVID-19 infection by creating antibodies that target and destroy the coronavirus. In order to do this, the immune system needs an antigen. It’s difficult to do this risk-free since all antigens exist directly on a virus. Luckily, vaccines safely expose antigens to our immune systems without the dangerous parts of the virus. In the case of COVID-19, the coronavirus’s antigen is the spike protein that covers its outer surface. Vaccines inject antigen-building instructions* and use our own cellular machinery to build the coronavirus antigen from scratch. When exposed to the spike protein, the immune system begins to assemble antigen-specific antibodies. These antibodies wait for the opportunity to attack the real spike protein when a coronavirus enters the body. Since antibodies decrease over time, booster immunizations help to maintain a strong line of defense. *While different vaccine technologies exist, they all do a similar thing: introduce an antigen and build a stronger immune system.

How COVID Antiviral Pills Work

Antiviral pills, unlike vaccines, are not a preventative strategy. Instead, they treat an infected individual experiencing symptoms from the virus. Two drugs are now entering the market. Merck & Co.’s Lagevrio®, composed of one molecule, and Pfizer’s Paxlovid®, composed of two. These medications disrupt specific processes in the viral assembly line to choke the virus’s ability to replicate.

The Mechanism of Molnupiravir

RNA-dependent RNA Polymerase (RdRp) is a cellular component that works similar to a photocopying machine for the virus’s genetic instructions. An infected host cell is forced to produce RdRp, which starts generating more copies of the virus’s RNA. Molnupiravir, developed by Merck & Co., is a polymerase inhibitor. It inserts itself into the viral instructions that RdRp is copying, jumbling the contents. The RdRp then produces junk.

The Mechanism of Nirmatrelvir + Ritonavir

A replicating virus makes proteins necessary for its survival in a large, clumped mass called a polyprotein. A cellular component called a protease cuts a virus’s polyprotein into smaller, workable pieces. Pfizer’s antiviral medication is a protease inhibitor made of two pills: With a faulty polymerase or a large, unusable polyprotein, antiviral medications make it difficult for the coronavirus to replicate. If treated early enough, they can lessen the virus’s impact on the body.

The Future of COVID Antiviral Pills and Medications

Antiviral medications seem to have a bright future ahead of them. COVID-19 antivirals are based on early research done on coronaviruses from the 2002-04 SARS-CoV and the 2012 MERS-CoV outbreaks. Current breakthroughs in this technology may pave the way for better pharmaceuticals in the future. One half of Pfizer’s medication, ritonavir, currently treats many other viruses including HIV/AIDS. Gilead Science is currently developing oral derivatives of remdesivir, another polymerase inhibitor currently only offered to inpatients in the United States. More coronavirus antivirals are currently in the pipeline, offering a glimpse of control on the looming presence of COVID-19. Author’s Note: The medical information in this article is an information resource only, and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes. Please talk to your doctor before undergoing any treatment for COVID-19. If you become sick and believe you may have symptoms of COVID-19, please follow the CDC guidelines.