The Times They Are A-Changin’

The Numbers Behind the New York Times’ digital transition

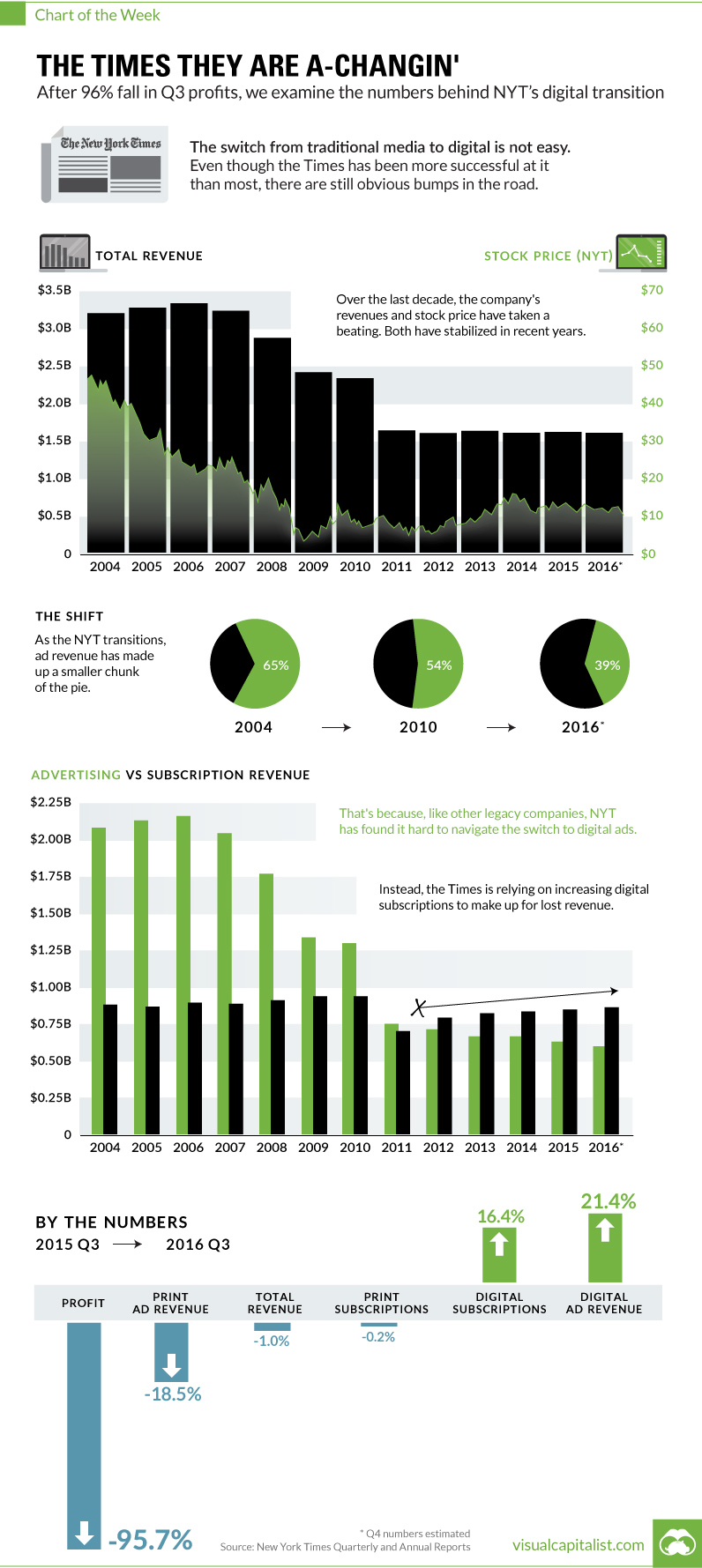

The Chart of the Week is a weekly Visual Capitalist feature on Fridays. For the most part, legacy print media stalwarts are dying a death by a thousand cuts. There are exceptions to this rule, and The New York Times is often touted as the best example of an old-school media company that is successfully navigating the challenging transition to digital. They’ve experimented with different types of content and tactics to get eyeballs, while also shifting their company-wide strategy and culture to take a digital-first approach. While pundits give credit to the Times for their latest efforts, this doesn’t mean it’s been an easy transition for the iconic newspaper. The path forward has been littered with roadbumps, and the most recent one is hard to ignore for shareholders. Earlier this week, The New York Times announced a 95.7% decrease in quarterly profit. We dug a little deeper in this week’s chart to provide some context behind the newspaper’s challenges in maintaining its relevance in the 21st century.

Goodbye, Ad Dollars

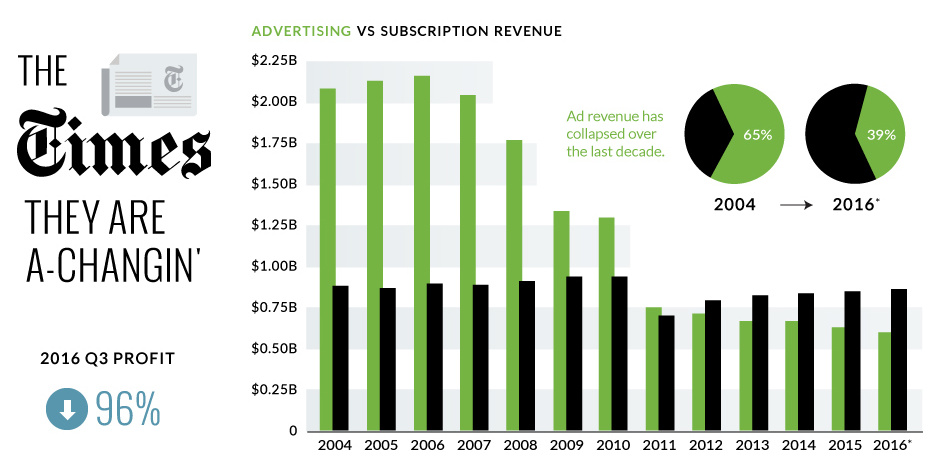

The primary challenge faced by the Times is pretty obvious. In the early 2000s, the company easily made over $2 billion in advertising revenue per year. Today, they make about $600 million from ads. Why has the transition to digital hurt ad revenues so much? There are a bunch of reasons, but here’s a few of them:

Physical circulation of The New York Times and other newspapers is dropping rapidly. Traditional display ads aren’t particularly effective, and are part of the “old-school” of digital thought. Programmatic bidding drives down prices for these ads, bringing in even less revenue. Digital lends itself to long-term, results-driven campaigns. It takes time to set these up and measure them properly, especially at scale. Ads need to match the editorial stream to be effective. Quality over quantity. There’s more competition in the digital space, which is a stark contrast to the distribution oligopolies enjoyed by big newspapers in the legacy era. Madison Avenue is also slow at switching to digital, which only adds to the lag time.

These are just some of the reasons why advertising was able to make up 65% of the Times’ revenues in 2004, but only 39% in 2016.

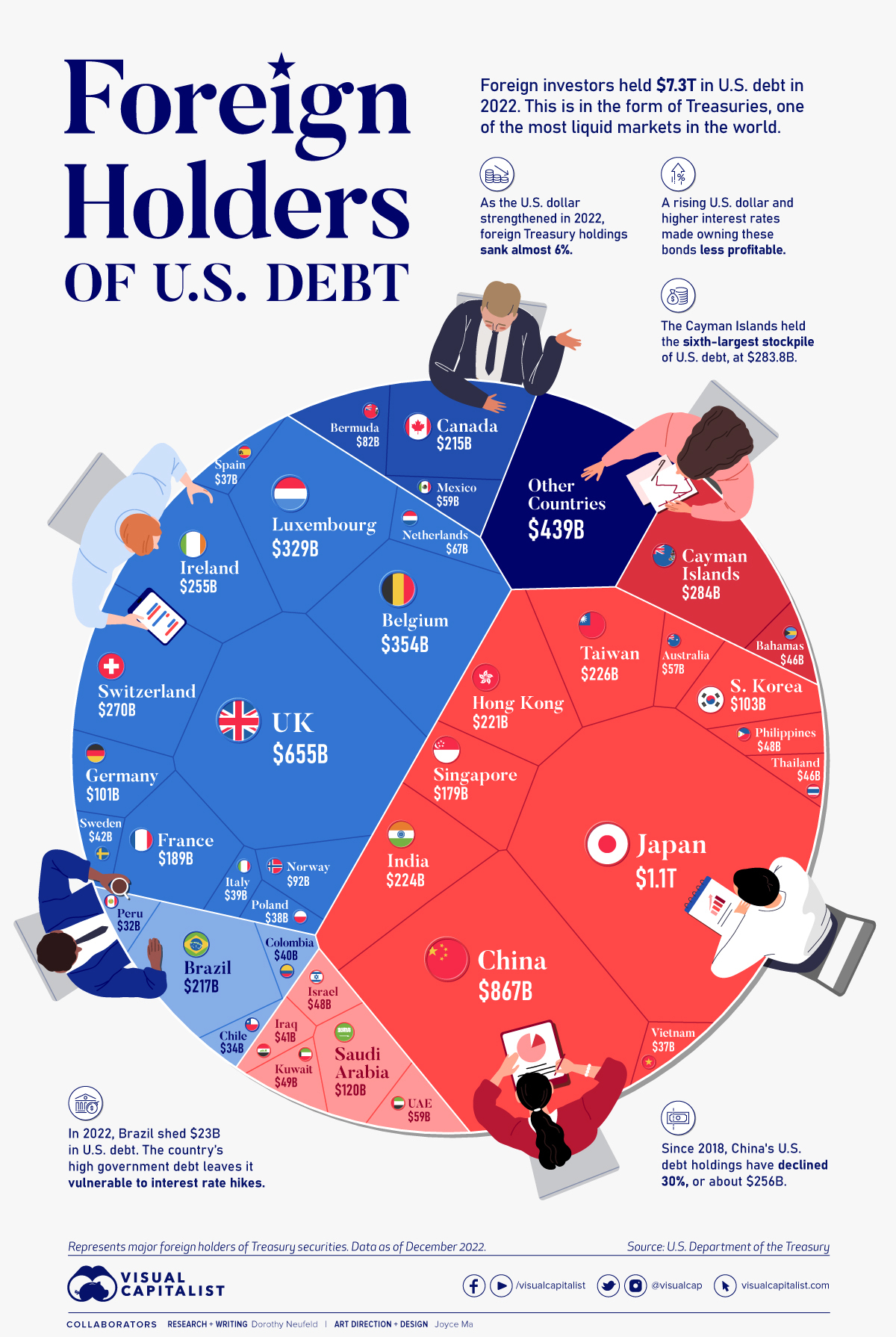

Hello, Digital Subscriptions

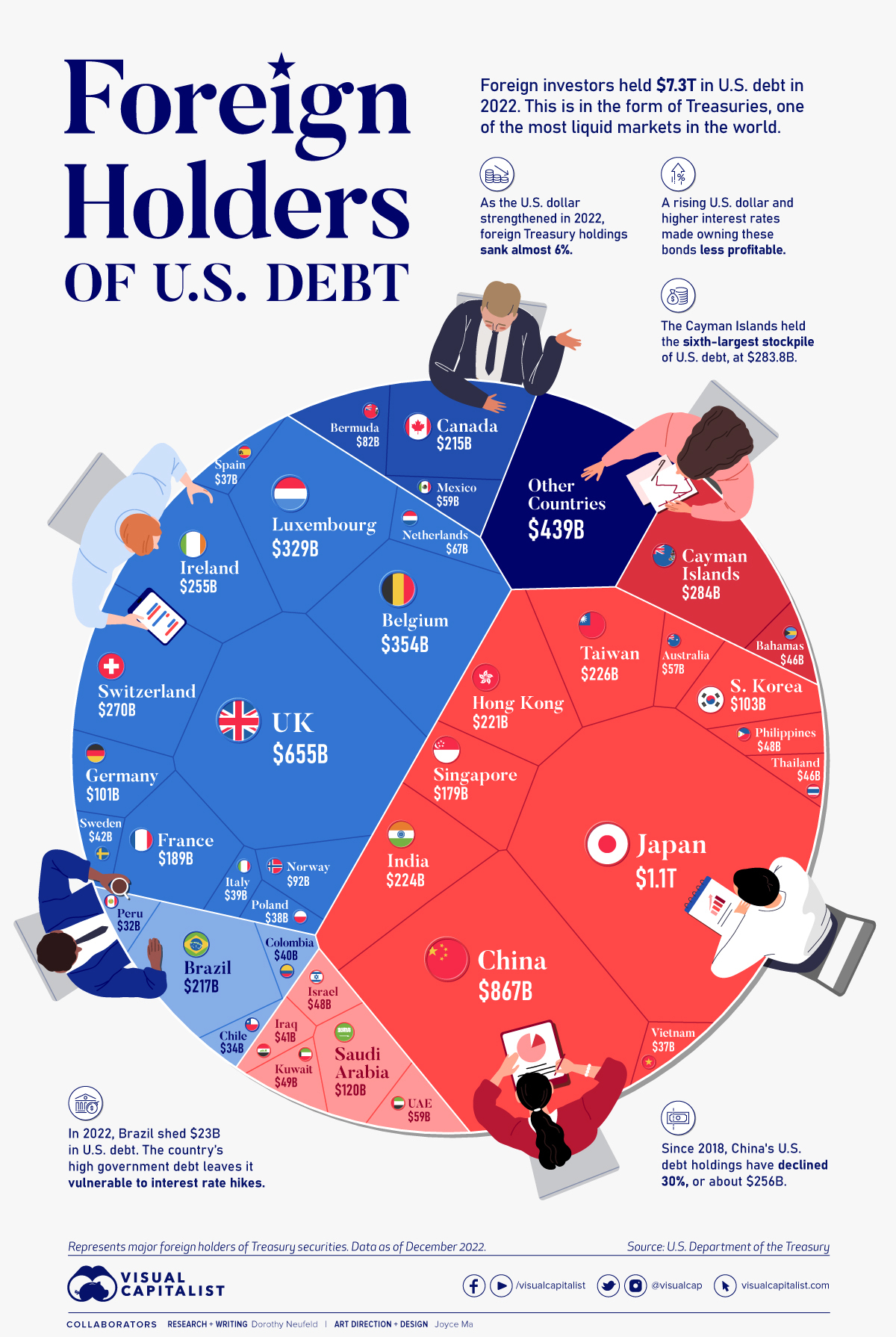

While I don’t personally agree that a paywall is a long-term answer to any of their problems, it is true that the New York Times has used this as a temporary crutch to at least counter lost ad dollars. In Q3 2016, revenue from digital-only subscriptions increased 16.4%, and money coming in from subscriptions has increased year-on-year since 2011. Sometime between 2011 and 2012, subscription revenue (powered by digital-only subscriptions) passed ad revenues as the most important source of incoming cash for the company. The ramp-up has been impressive, and The New York Times now has 1.6 million digital subscribers. My personal take? Digital subscriptions will plateau in the next five years or maybe sooner. Further, I think that content that isn’t industry or niche-specific will generally drift towards being free for users over time. The New York Times will have to solve their ad problem, but the paywall will buy them a bit of time to do so. on These are in the form of Treasury securities, some of the most liquid assets worldwide. Central banks use them for foreign exchange reserves and private investors flock to them during flights to safety thanks to their perceived low default risk. Beyond these reasons, foreign investors may buy Treasuries as a store of value. They are often used as collateral during certain international trade transactions, or countries can use them to help manage exchange rate policy. For example, countries may buy Treasuries to protect their currency’s exchange rate from speculation. In the above graphic, we show the foreign holders of the U.S. national debt using data from the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

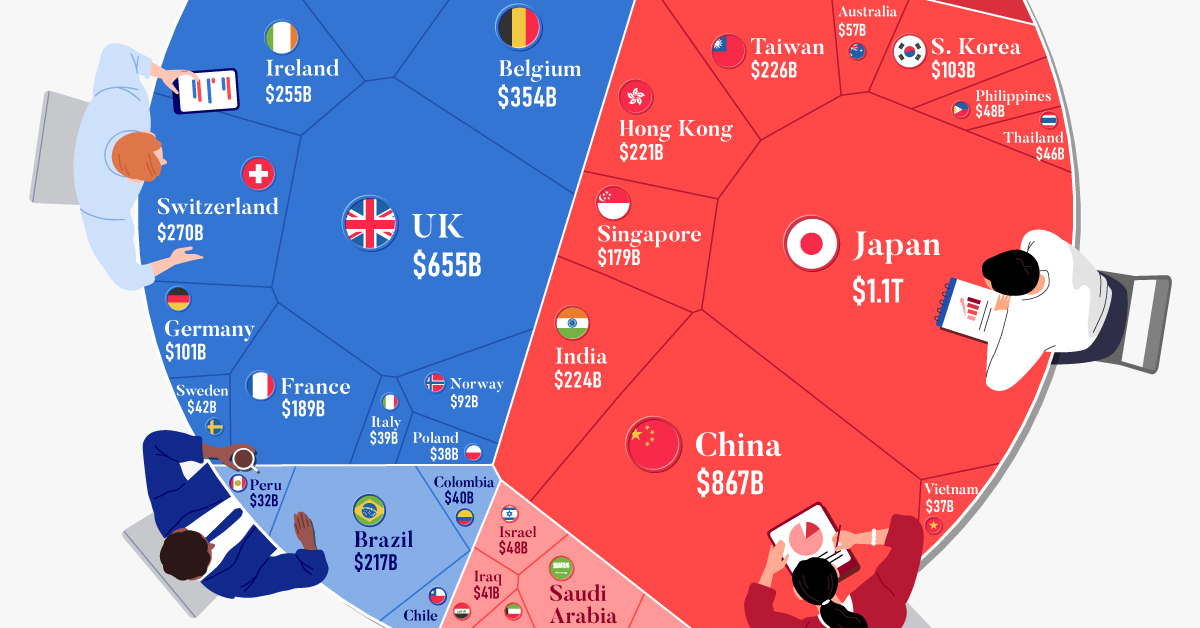

Top Foreign Holders of U.S. Debt

With $1.1 trillion in Treasury holdings, Japan is the largest foreign holder of U.S. debt. Japan surpassed China as the top holder in 2019 as China shed over $250 billion, or 30% of its holdings in four years. This bond offloading by China is the one way the country can manage the yuan’s exchange rate. This is because if it sells dollars, it can buy the yuan when the currency falls. At the same time, China doesn’t solely use the dollar to manage its currency—it now uses a basket of currencies. Here are the countries that hold the most U.S. debt: As the above table shows, the United Kingdom is the third highest holder, at over $655 billion in Treasuries. Across Europe, 13 countries are notable holders of these securities, the highest in any region, followed by Asia-Pacific at 11 different holders. A handful of small nations own a surprising amount of U.S. debt. With a population of 70,000, the Cayman Islands own a towering amount of Treasury bonds to the tune of $284 billion. There are more hedge funds domiciled in the Cayman Islands per capita than any other nation worldwide. In fact, the four smallest nations in the visualization above—Cayman Islands, Bermuda, Bahamas, and Luxembourg—have a combined population of just 1.2 million people, but own a staggering $741 billion in Treasuries.

Interest Rates and Treasury Market Dynamics

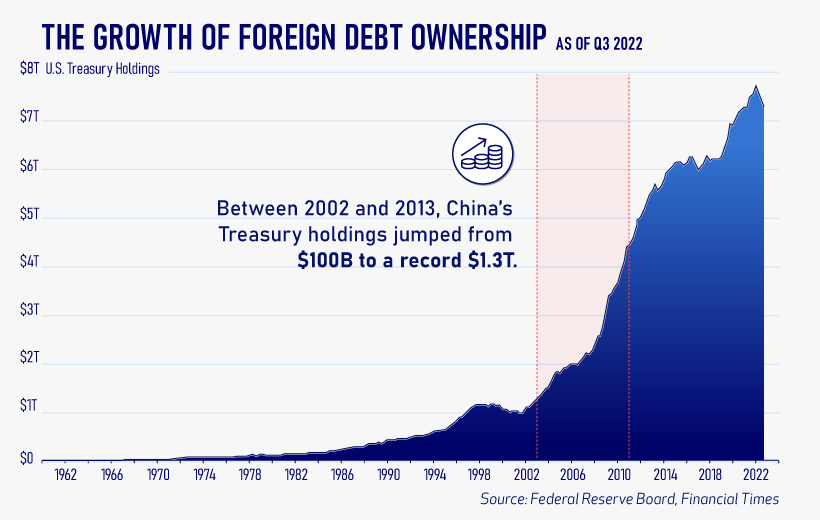

Over 2022, foreign demand for Treasuries sank 6% as higher interest rates and a strong U.S. dollar made owning these bonds less profitable. This is because rising interest rates on U.S. debt makes the present value of their future income payments lower. Meanwhile, their prices also fall. As the chart below shows, this drop in demand is a sharp reversal from 2018-2020, when demand jumped as interest rates hovered at historic lows. A similar trend took place in the decade after the 2008-09 financial crisis when U.S. debt holdings effectively tripled from $2 to $6 trillion.

Driving this trend was China’s rapid purchase of Treasuries, which ballooned from $100 billion in 2002 to a peak of $1.3 trillion in 2013. As the country’s exports and output expanded, it sold yuan and bought dollars to help alleviate exchange rate pressure on its currency. Fast-forward to today, and global interest-rate uncertainty—which in turn can impact national currency valuations and therefore demand for Treasuries—continues to be a factor impacting the future direction of foreign U.S. debt holdings.