America’s wealthiest have made their fortunes in a wide variety of ways, but there is one thing many of these tycoons have in common: 80% of billionaires picked up a Bachelor’s degree at some point in their lives. Today’s chart visualizes data from Adview to show the educational paths and early working years of billionaires on the elite Forbes 400 list, a ranking of the 400 wealthiest people in the United States.

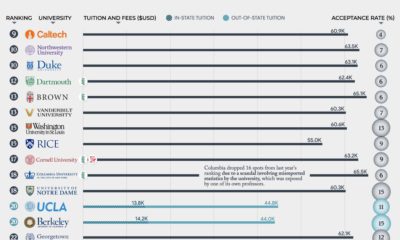

In a League of Its Own

Unsurprisingly, many U.S. billionaires got their start at Ivy League schools. Seven out of the top 10 billionaire-producing universities bear that prestigious designation. Here’s the full count of billionaire graduates from the top 10 universities: Billionaire graduates aren’t just limited to Ivy League institutions, however. California’s Stanford and USC also rank highly, having graduated 23 billionaires between them.

What Are the Most Popular Degrees?

Degrees in the fields of economics, finance, and business are obvious springboards into the Forbes 400 list, but it’s interesting to see that many went the arts and social sciences route. Politics, history, English, psychology, and philosophy are also among the ten most popular fields studied. It’s worth noting that degree classification can vary depending on the university and course in question. For example, a degree in mathematics could be considered a Bachelor of Sciences, or, Bachelor of Arts. Similarly, a Bachelor of Economics, or, a Bachelor of Social Sciences could be awarded to somebody who studied the subject of economics.

The Power of UPenn

While Harvard and Yale are highly coveted educational institutions, it’s the University of Pennsylvania that provides the most fertile breeding ground for billionaires. Here are some notable – and notorious – alumni, including those who attended its prestigious Wharton School: *In their sophomore years, Warren Buffett transferred out to the University of Nebraska, while Donald Trump transferred in from Fordham University.

What are the Most Common First Jobs?

Many billionaires started out as self-employed, or followed in their family’s footsteps:

11% of billionaires started at their own company 19% of them started at their family company

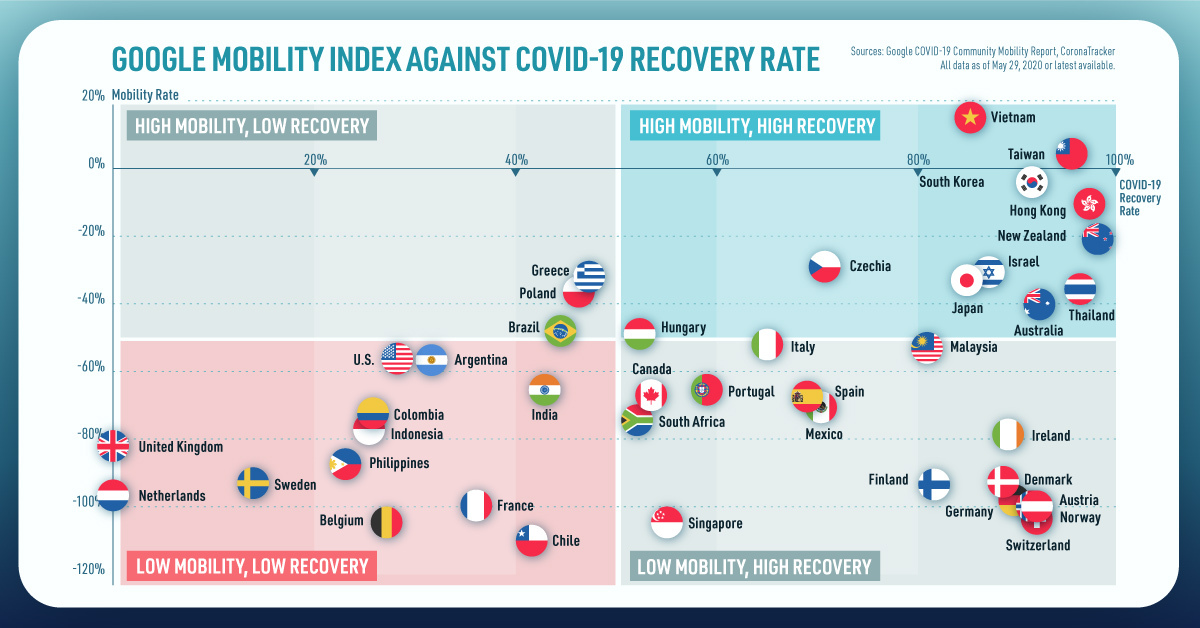

However, these individuals were excluded from Adview’s analysis. Out of the remaining 330 billionaires, salesperson tops the list of first jobs, narrowly edging out the military category. While there are many possible paths to financial success in the U.S., only a minority of Americans are likely to reach billionaire status in their lifetimes. That said, studying economics at Wharton certainly wouldn’t hurt their chances. on Today’s chart measures the extent to which 41 major economies are reopening, by plotting two metrics for each country: the mobility rate and the COVID-19 recovery rate: Data for the first measure comes from Google’s COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports, which relies on aggregated, anonymous location history data from individuals. Note that China does not show up in the graphic as the government bans Google services. COVID-19 recovery rates rely on values from CoronaTracker, using aggregated information from multiple global and governmental databases such as WHO and CDC.

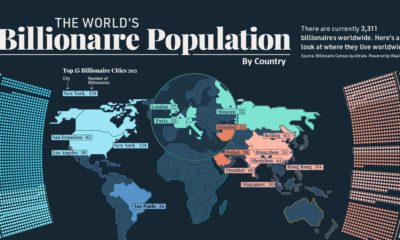

Reopening Economies, One Step at a Time

In general, the higher the mobility rate, the more economic activity this signifies. In most cases, mobility rate also correlates with a higher rate of recovered people in the population. Here’s how these countries fare based on the above metrics. Mobility data as of May 21, 2020 (Latest available). COVID-19 case data as of May 29, 2020. In the main scatterplot visualization, we’ve taken things a step further, assigning these countries into four distinct quadrants:

1. High Mobility, High Recovery

High recovery rates are resulting in lifted restrictions for countries in this quadrant, and people are steadily returning to work. New Zealand has earned praise for its early and effective pandemic response, allowing it to curtail the total number of cases. This has resulted in a 98% recovery rate, the highest of all countries. After almost 50 days of lockdown, the government is recommending a flexible four-day work week to boost the economy back up.

2. High Mobility, Low Recovery

Despite low COVID-19 related recoveries, mobility rates of countries in this quadrant remain higher than average. Some countries have loosened lockdown measures, while others did not have strict measures in place to begin with. Brazil is an interesting case study to consider here. After deferring lockdown decisions to state and local levels, the country is now averaging the highest number of daily cases out of any country. On May 28th, for example, the country had 24,151 new cases and 1,067 new deaths.

3. Low Mobility, High Recovery

Countries in this quadrant are playing it safe, and holding off on reopening their economies until the population has fully recovered. Italy, the once-epicenter for the crisis in Europe is understandably wary of cases rising back up to critical levels. As a result, it has opted to keep its activity to a minimum to try and boost the 65% recovery rate, even as it slowly emerges from over 10 weeks of lockdown.

4. Low Mobility, Low Recovery

Last but not least, people in these countries are cautiously remaining indoors as their governments continue to work on crisis response. With a low 0.05% recovery rate, the United Kingdom has no immediate plans to reopen. A two-week lag time in reporting discharged patients from NHS services may also be contributing to this low number. Although new cases are leveling off, the country has the highest coronavirus-caused death toll across Europe. The U.S. also sits in this quadrant with over 1.7 million cases and counting. Recently, some states have opted to ease restrictions on social and business activity, which could potentially result in case numbers climbing back up. Over in Sweden, a controversial herd immunity strategy meant that the country continued business as usual amid the rest of Europe’s heightened regulations. Sweden’s COVID-19 recovery rate sits at only 13.9%, and the country’s -93% mobility rate implies that people have been taking their own precautions.

COVID-19’s Impact on the Future

It’s important to note that a “second wave” of new cases could upend plans to reopen economies. As countries reckon with these competing risks of health and economic activity, there is no clear answer around the right path to take. COVID-19 is a catalyst for an entirely different future, but interestingly, it’s one that has been in the works for a while. —Carmen Reinhart, incoming Chief Economist for the World Bank Will there be any chance of returning to “normal” as we know it?