In the wake of countrywide protests surrounding the killing of George Floyd, questions around the militarization of police forces have taken center stage once again. How did so many police departments across the United States end up with bomb-proof trucks and night vision goggles? Where are departments acquiring this equipment, and at what cost? These questions and more are answered by data from the Defense Logistics Agency, which oversees the 1033 Program. The visualization above tracks the flow of military equipment to law enforcement over the past decade. A note on the data: Much of the equipment acquired through the program is already used – and often obsolete by military standards. As well, the 1033 dataset captures shipments of equipment. Over time, items can be transferred between departments, meaning these official records may be less reflective of specific police department inventories as time goes on. For these reasons, we decided to cap our analysis to looking at the last decade (2010-2020) of transfers.

Free Military Surplus for Law Enforcement

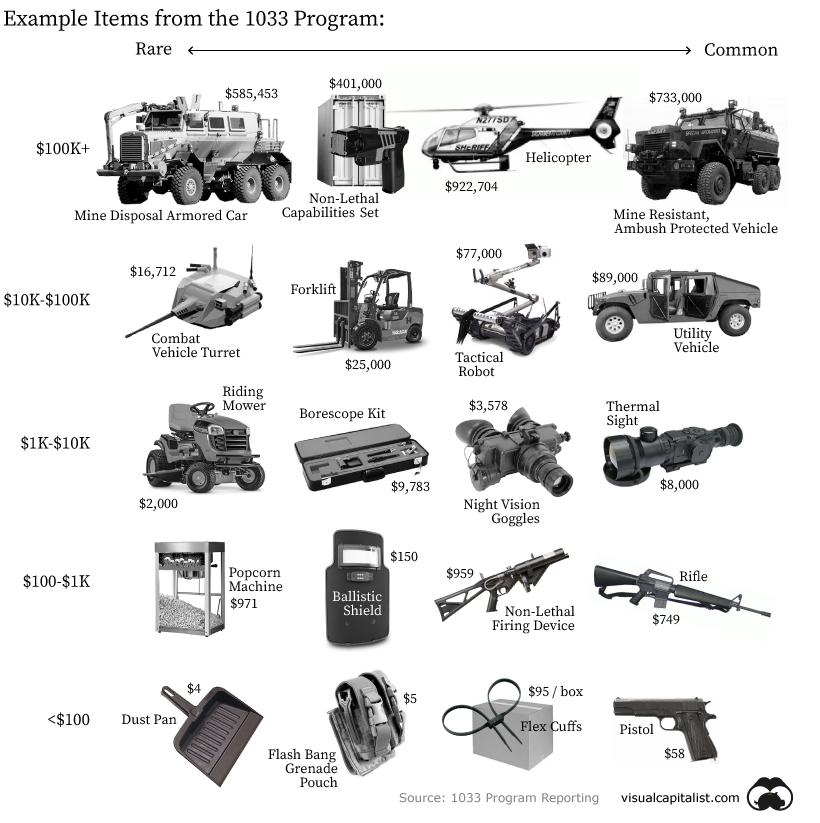

The 1033 Program was conceived in the years following Operation Desert Storm, just as America’s violent crime rate was hitting an all-time high. During this era, America’s “war on drugs” and tough-on-crime political platforms provided the impetus for the militarization of police forces around the country. The 1033 program has been likened to Craigslist’s “Free Stuff” section, and the comparison is apt. The mechanics of the program are relatively straightforward. Outdated military gear is transferred (at no cost) to state and local law enforcement agencies who go through the application process. The equipment is loaned to agencies, who are only responsible only for shipping and subsequent operating costs (e.g. fuel, spare parts). Law enforcement agencies gain access to a vast array of military surplus, from office supplies and thermal underwear up to armored vehicles and multi-million dollar communications systems. Also included in the mix are medical supplies and gear to aid in search and rescue operations. Since the program’s inception, over $7.4 billion worth of property has been transferred.

One of the most popular items acquired by police departments is the Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicle, or MRAP. Over the past decade, over 1,000 of these vehicles were transferred from the military to law enforcement agencies. This includes places like Monett, Missouri (population 9,000), which is on record as receiving two MRAP vehicles. Night vision equipment is extremely popular as well. Items like goggles, scopes, and surveillance equipment – which can run thousands of dollars per unit – have been shipped to police departments around the country. Of course, military surplus isn’t just about fancy vehicles and weaponry. The Meade County Sheriff’s Office in Kentucky is on record for ordering a single box of toilet paper just as COVID-19 was on the rise in that state.

Shipments at the State Level

Since the army is willing to part with excess equipment, cash-strapped police departments are happy to oblige. More than $1.7 billion of surplus has been transferred over to police around the country over the past decade. The two biggest spenders, California and Texas, combined to acquire a total of $271 million in equipment, but looking at things on a per capita basis helps to show the states that were most enthusiastic about the 1033 Program in more relative terms. Tennessee had by far the highest spending considering its population, with police departments in the state acquiring $20 worth of equipment per person. With the exception of Arizona, all the states that rank highly in that metric have per capita police spending that sits well below the U.S. average. On the flip side, New York came in at a fraction of that amount, acquiring only $1.74 worth of equipment for every person in the state. Of course, it’s worth noting that New York had the highest police expenditure in the country (after Washington DC).

Who got the Goods?

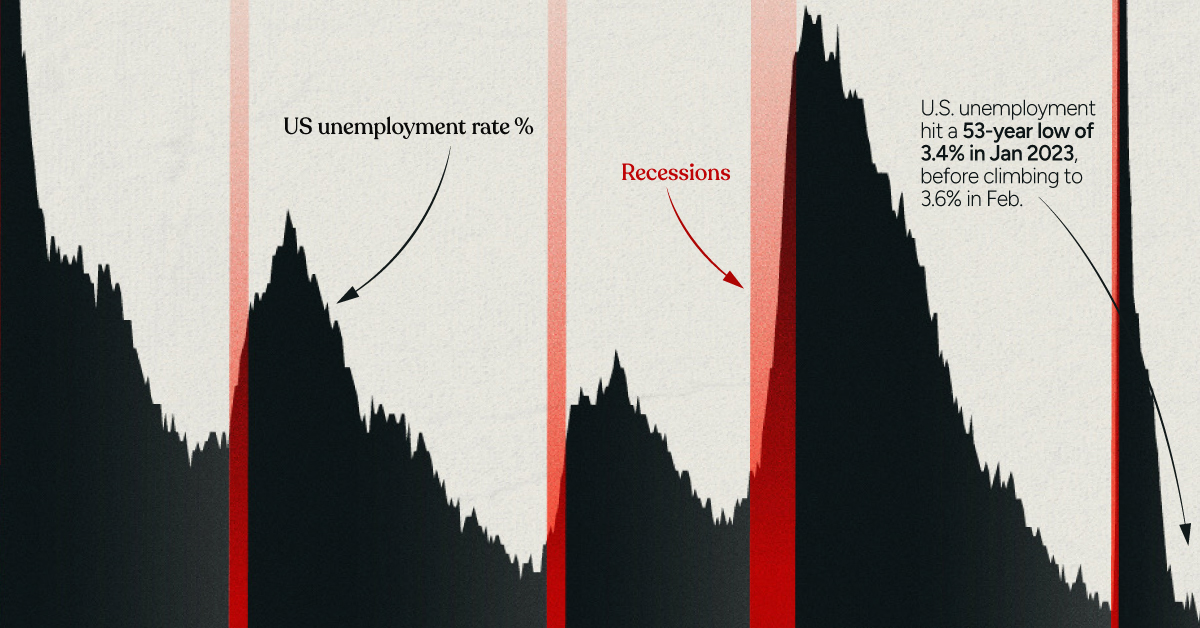

Not surprisingly, state-level law enforcement agencies topped the list. For example, the Arizona Department of Public Safety received multiple airplanes valued at $17 million per unit. California’s highway patrol received the most expensive single item on the list – a $22 million aircraft. For a more local perspective, here’s a look at the top 20 police departments by value of military equipment acquired: On its own, Houston police department received as much as the bottom five states combined. Nearly 400 other police departments also broke the $1 million barrier, and over 2,026 departments around the country received over $100,000 in goods. on Both figures surpassed analyst expectations by a wide margin, and in January, the unemployment rate hit a 53-year low of 3.4%. With the recent release of February’s numbers, unemployment is now reported at a slightly higher 3.6%. A low unemployment rate is a classic sign of a strong economy. However, as this visualization shows, unemployment often reaches a cyclical low point right before a recession materializes.

Reasons for the Trend

In an interview regarding the January jobs data, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made a bold statement: While there’s nothing wrong with this assessment, the trend we’ve highlighted suggests that Yellen may need to backtrack in the near future. So why do recessions tend to begin after unemployment bottoms out?

The Economic Cycle

The economic cycle refers to the economy’s natural tendency to fluctuate between periods of growth and recession. This can be thought of similarly to the four seasons in a year. An economy expands (spring), reaches a peak (summer), begins to contract (fall), then hits a trough (winter). With this in mind, it’s reasonable to assume that a cyclical low in the unemployment rate (peak employment) is simply a sign that the economy has reached a high point.

Monetary Policy

During periods of low unemployment, employers may have a harder time finding workers. This forces them to offer higher wages, which can contribute to inflation. For context, consider the labor shortage that emerged following the COVID-19 pandemic. We can see that U.S. wage growth (represented by a three-month moving average) has climbed substantially, and has held above 6% since March 2022. The Federal Reserve, whose mandate is to ensure price stability, will take measures to prevent inflation from climbing too far. In practice, this involves raising interest rates, which makes borrowing more expensive and dampens economic activity. Companies are less likely to expand, reducing investment and cutting jobs. Consumers, on the other hand, reduce the amount of large purchases they make. Because of these reactions, some believe that aggressive rate hikes by the Fed can either cause a recession, or make them worse. This is supported by recent research, which found that since 1950, central banks have been unable to slow inflation without a recession occurring shortly after.

Politicians Clash With Economists

The Fed has raised interest rates at an unprecedented pace since March 2022 to combat high inflation. More recently, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell warned that interest rates could be raised even higher than originally expected if inflation continues above target. Senator Elizabeth Warren expressed concern that this would cost Americans their jobs, and ultimately, cause a recession. Powell remains committed to bringing down inflation, but with the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, some analysts believe there could be a pause coming in interest rate hikes. Editor’s note: just after publication of this article, it was confirmed that U.S. interest rates were hiked by 25 basis points (bps) by the Federal Reserve.