Today, around 6,000 officially classified products pass through the world’s ports, and digital products and services zip across country lines creating an extra layer of difficulty in measuring economic activity. To try to understand this enormous level of economic complexity, the team at Harvard’s Growth Lab have created the Country Complexity Ranking. Here’s a look at the top 50 countries in the ranking: Source Japan, Switzerland, and South Korea sit at the top of the ranking. Czech Republic – which was recently ranked as the most attractive manufacturing destination in Europe – has a strong showing, ranking 6th in the world. The United States slipped out of the top 10 into 12th position.

The Power of Productive Knowledge

Highly ranked countries tend to have the following attributes:

• A high diversity of exported products • Sophisticated and unique exported products (i.e. few other countries produce similar products)

In short, the ranking hinges on the concept of “productive knowledge” – or the tacit ability to produce a product. Muhammed Yildirim, of Harvard University, has thought up a useful analogy for thinking about the role of productive knowledge in the complexity of an economy: “Suppose that each type of productive knowledge is a letter and each product is a word composed of these letters. Like the game of Scrabble, each country holds a set of letters with plenty of copies of each letter and tries to make words out of these letters. For instance, with letters like A, C and T, one can construct words like CAT or ACT. Then our problem of measuring economic complexity resembles interpreting how many different letters there are in each country’s portfolio. Some letters, like A and E, go in many words, whereas other letters, like X and Q, are used in very few. Extending this analogy to the countries and products, only those with a larger diversity of letters will be able to make more and more unique products. On the other hand, words that require more letters will be made only in the countries that have all the requisite pieces.”

Not All Exports are Created Equal

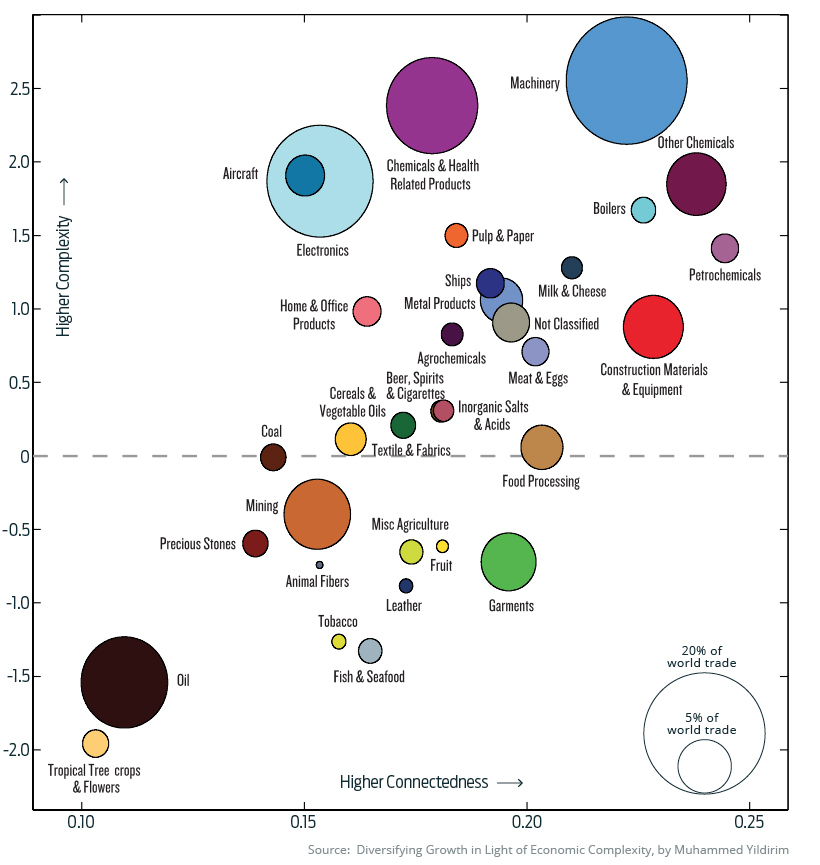

Much like the rack of letters in a Scrabble game, the elements of every export-driven economy can be broken down and quantified. The resulting categories encompass everything from rendered pig fat to integrated circuits, each contributing to the country’s overall score.

Agricultural and extractive industries tend to score lower on the complexity scale. Machinery can be highly complex to produce and is connected to many facets of the global economy. Visualizing this overall mix of categories can provide a unique perspective beyond big picture numbers like GDP. Below are a few real world examples of export markets on both ends of the complexity spectrum.

Japan

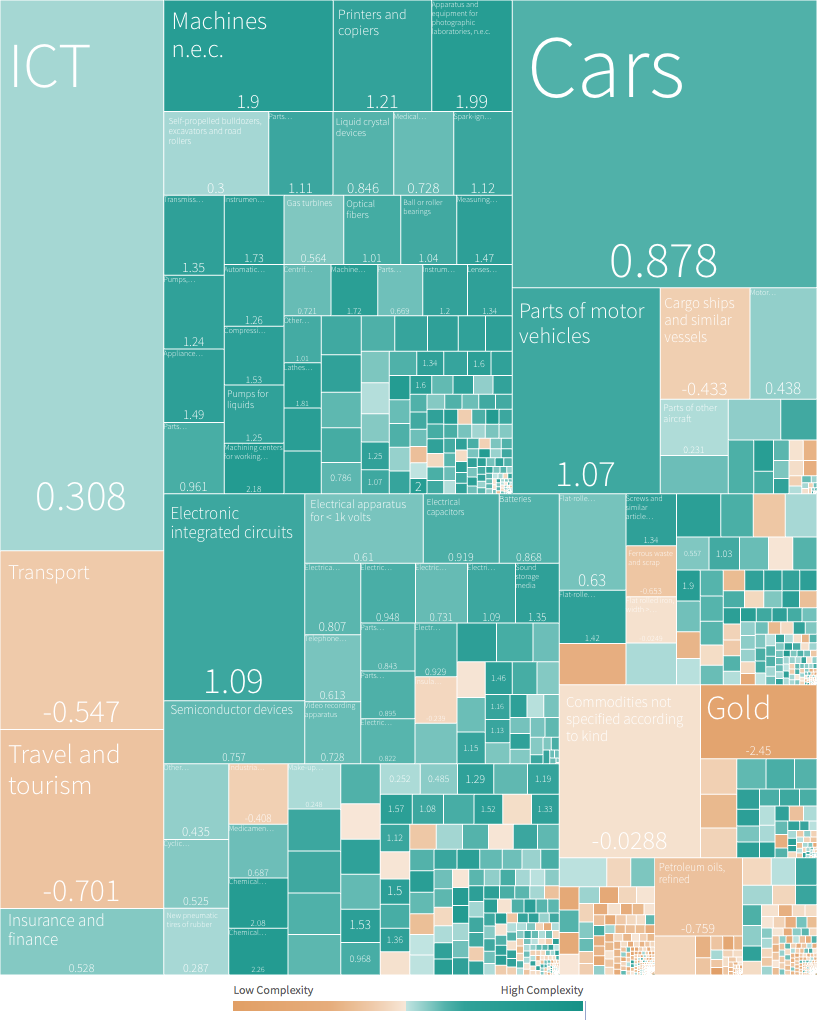

Since this ranking began in the mid-1990s, Japan has never been bumped from the top spot. Due to a restricted land mass and some ingenuity, Japan has become the prototypical example of a low-ubiquity, high-sophistication export economy.

Interactive breakdown Cars and electronics are obvious standouts, but there numerous other high-value product categories in the mix as well. The country also has a wide variety of high value exports and trading partners, lowering the risk of a trade war or industry downturn crippling the country’s economy.

Australia

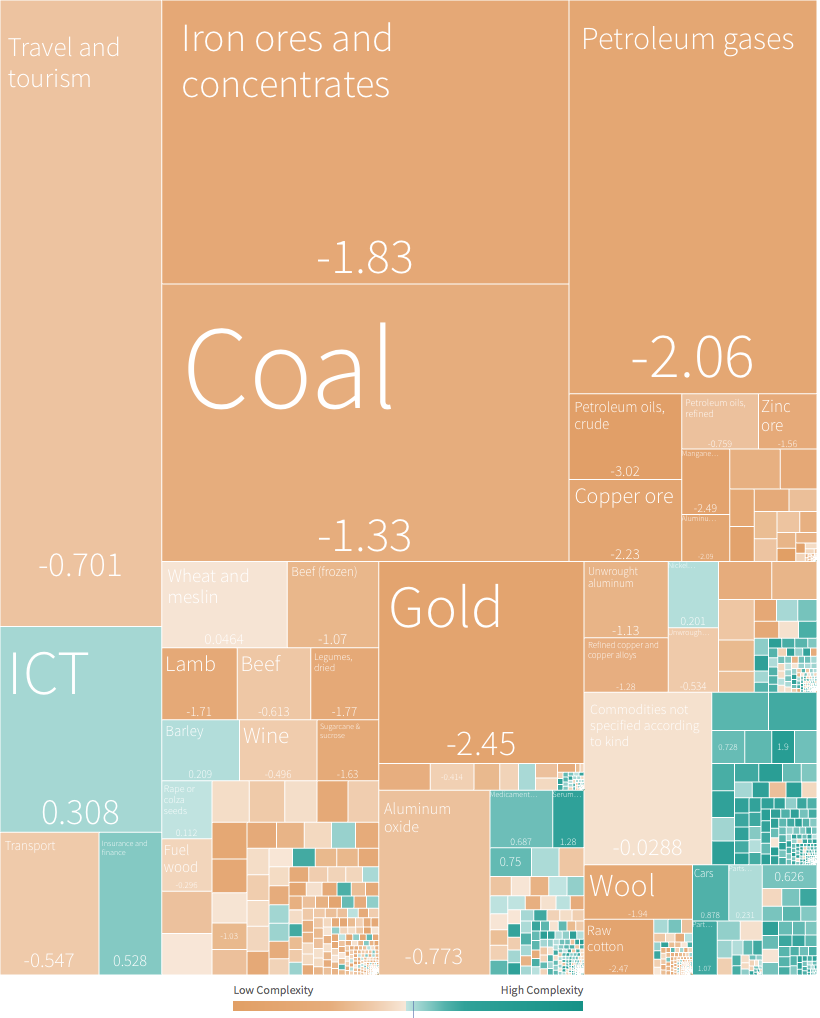

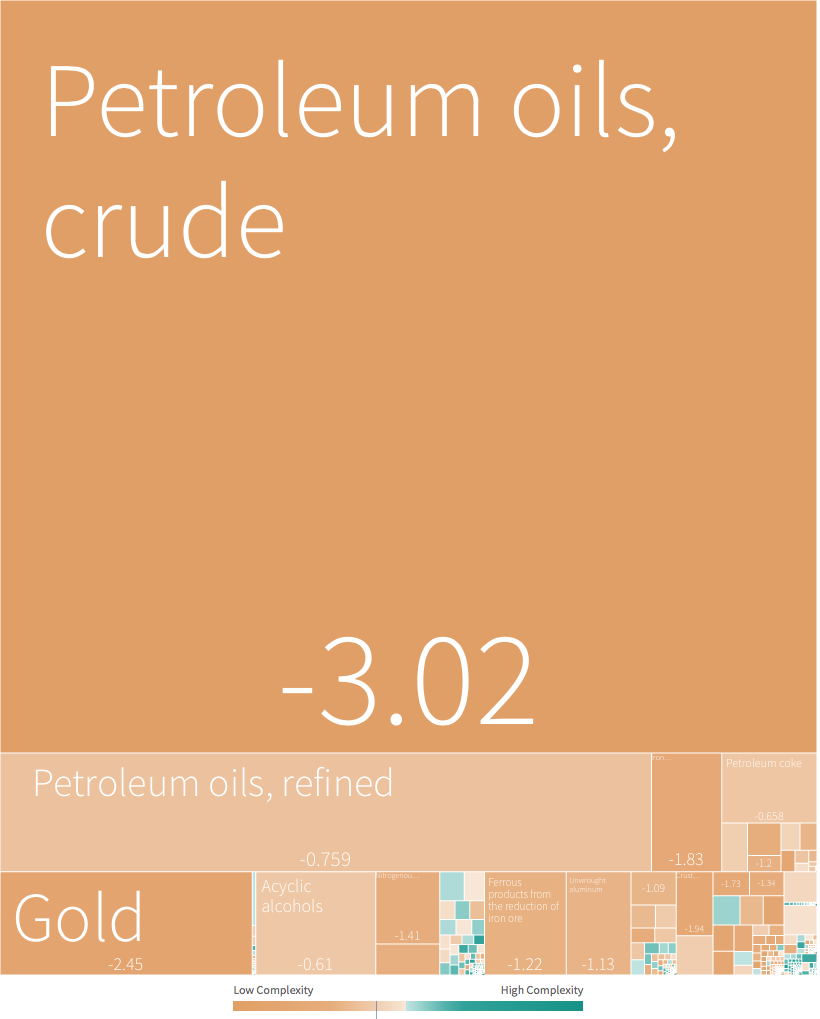

Many will be surprised to learn that Australia sits in the lower third of this complexity ranking. Although Australia’s global ranking is high in a myriad of categories – household wealth per person, for example – its economic complexity score is -0.60, much lower than expected for its income level. Looking at the breakdown below, there are clues as to why this might be the case.

Interactive breakdown Australia’s largest exports are in low complexity categories, such as minerals and agriculture. To compound matters, the country’s economy is heavily linked to China’s. To underscore this point, a recent study found that a 5% drop in China’s GDP would result in a 2.5% dip in Australia’s.

Venezuela

It’s no secret that Venezuela has seen some tough times in recent years. The chart below shows just how reliant Venezuela was on oil exports to sustain its economy.

Interactive breakdown An over-reliance on a single export can leave a country extremely vulnerable in the event of price volatility or geopolitical events. In the case of Venezuela, three quarters of their export economy was comprised of crude oil – one of the lowest scoring product categories in the ranking.

The Rush to Diversify

A low level of economic complexity isn’t necessarily a problem. Many countries with middle-to-low scores in the ranking have great standards of living and a high level of wealth. Countries like Canada, Norway, and Australia were all well down the list. On the other hand, some countries have made diversification a priority. SoftBank’s $100 billion Vision Fund is partially the result of Saudi Arabia’s push to develop a diversified, knowledge-based economy. Other oil-rich nations, such as Kazakhstan, are also pushing to diversify in the face of the world’s evolving energy mix. As world economies evolve and the shift from fossil fuels continues, we will likely see economic complexity increase across the board. on But fast forward to the end of last week, and SVB was shuttered by regulators after a panic-induced bank run. So, how exactly did this happen? We dig in below.

Road to a Bank Run

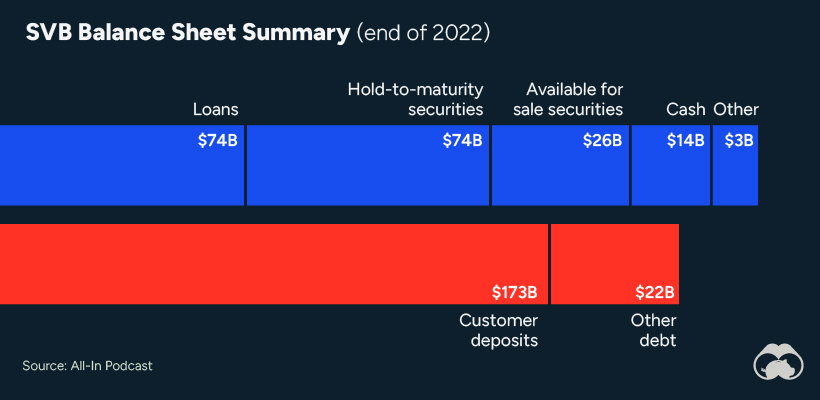

SVB and its customers generally thrived during the low interest rate era, but as rates rose, SVB found itself more exposed to risk than a typical bank. Even so, at the end of 2022, the bank’s balance sheet showed no cause for alarm.

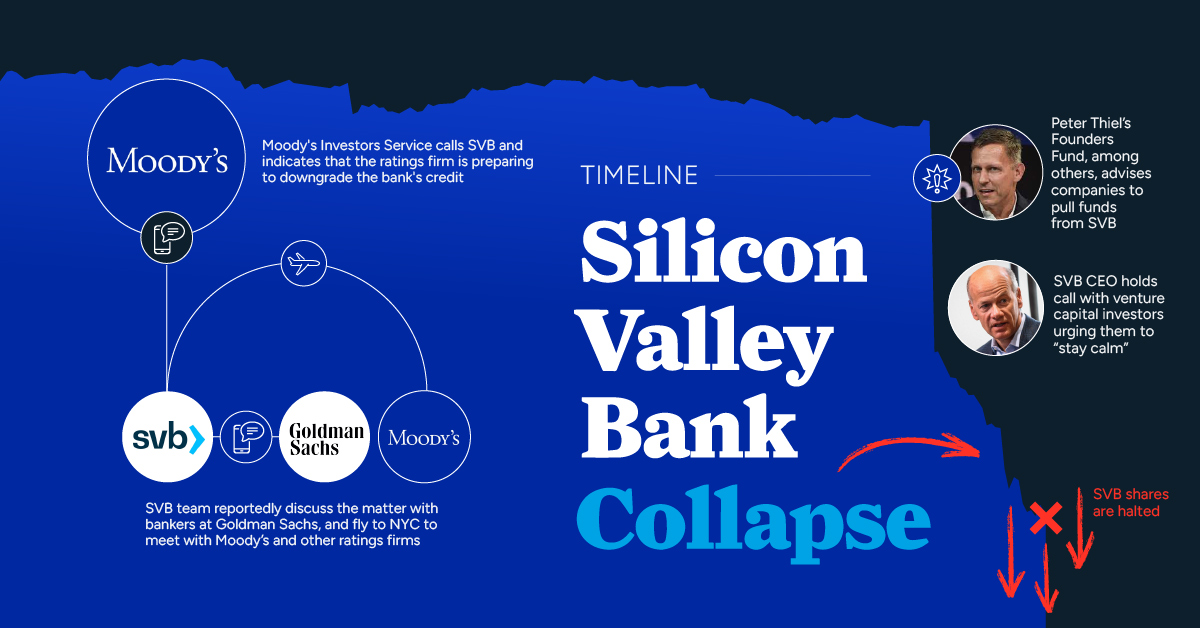

As well, the bank was viewed positively in a number of places. Most Wall Street analyst ratings were overwhelmingly positive on the bank’s stock, and Forbes had just added the bank to its Financial All-Stars list. Outward signs of trouble emerged on Wednesday, March 8th, when SVB surprised investors with news that the bank needed to raise more than $2 billion to shore up its balance sheet. The reaction from prominent venture capitalists was not positive, with Coatue Management, Union Square Ventures, and Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund moving to limit exposure to the 40-year-old bank. The influence of these firms is believed to have added fuel to the fire, and a bank run ensued. Also influencing decision making was the fact that SVB had the highest percentage of uninsured domestic deposits of all big banks. These totaled nearly $152 billion, or about 97% of all deposits. By the end of the day, customers had tried to withdraw $42 billion in deposits.

What Triggered the SVB Collapse?

While the collapse of SVB took place over the course of 44 hours, its roots trace back to the early pandemic years. In 2021, U.S. venture capital-backed companies raised a record $330 billion—double the amount seen in 2020. At the time, interest rates were at rock-bottom levels to help buoy the economy. Matt Levine sums up the situation well: “When interest rates are low everywhere, a dollar in 20 years is about as good as a dollar today, so a startup whose business model is “we will lose money for a decade building artificial intelligence, and then rake in lots of money in the far future” sounds pretty good. When interest rates are higher, a dollar today is better than a dollar tomorrow, so investors want cash flows. When interest rates were low for a long time, and suddenly become high, all the money that was rushing to your customers is suddenly cut off.” Source: Pitchbook Why is this important? During this time, SVB received billions of dollars from these venture-backed clients. In one year alone, their deposits increased 100%. They took these funds and invested them in longer-term bonds. As a result, this created a dangerous trap as the company expected rates would remain low. During this time, SVB invested in bonds at the top of the market. As interest rates rose higher and bond prices declined, SVB started taking major losses on their long-term bond holdings.

Losses Fueling a Liquidity Crunch

When SVB reported its fourth quarter results in early 2023, Moody’s Investor Service, a credit rating agency took notice. In early March, it said that SVB was at high risk for a downgrade due to its significant unrealized losses. In response, SVB looked to sell $2 billion of its investments at a loss to help boost liquidity for its struggling balance sheet. Soon, more hedge funds and venture investors realized SVB could be on thin ice. Depositors withdrew funds in droves, spurring a liquidity squeeze and prompting California regulators and the FDIC to step in and shut down the bank.

What Happens Now?

While much of SVB’s activity was focused on the tech sector, the bank’s shocking collapse has rattled a financial sector that is already on edge.

The four biggest U.S. banks lost a combined $52 billion the day before the SVB collapse. On Friday, other banking stocks saw double-digit drops, including Signature Bank (-23%), First Republic (-15%), and Silvergate Capital (-11%).

Source: Morningstar Direct. *Represents March 9 data, trading halted on March 10.

When the dust settles, it’s hard to predict the ripple effects that will emerge from this dramatic event. For investors, the Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen announced confidence in the banking system remaining resilient, noting that regulators have the proper tools in response to the issue.

But others have seen trouble brewing as far back as 2020 (or earlier) when commercial banking assets were skyrocketing and banks were buying bonds when rates were low.