However, without a frame of reference, numbers such as the death toll can be difficult to interpret. Mortalities attributed to the virus, for example, are often measured in the thousands of people per day globally—but is this number a little or a lot, relative to typical causes of death? Today’s graphic uses data from Our World in Data to provide context with the total number of worldwide daily deaths. It also outlines how many people who die each day from specific causes.

Worldwide Deaths by Cause

Nearly 150,000 people die per day worldwide, based on the latest comprehensive research published in 2017. Which diseases are the most deadly, and how many lives do they take per day? Here’s how many people die each day on average, sorted by cause: Cardiovascular diseases, or diseases of the heart and blood vessels, are the leading cause of death. However, their prominence is not reflected in our perceptions of death nor in the media. While the death toll for HIV/AIDS peaked in 2004, it still affects many people today. The disease causes over 2,600 daily deaths on average. Interestingly, terrorism and natural disasters cause very few deaths in relation to other causes. That said, these numbers can vary from day to day—and year to year—depending on the severity of each individual instance.

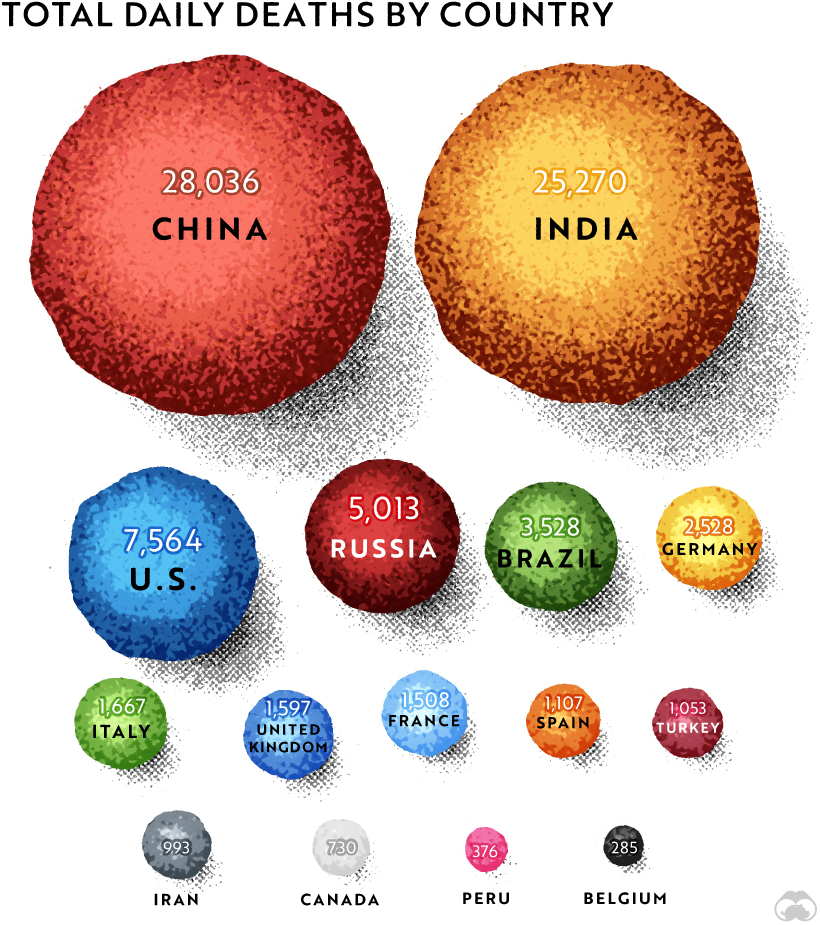

Total Daily Deaths by Country

On a national level, these statistics vary further. Below are the total deaths from all causes for selected countries, based on 2017 data. China and India both see more than 25,000 total deaths per day, due to their large populations. However, with 34.7 daily deaths per million people each day, Russia has the highest deaths proportional to population out of any of these countries.

Keeping Perspective

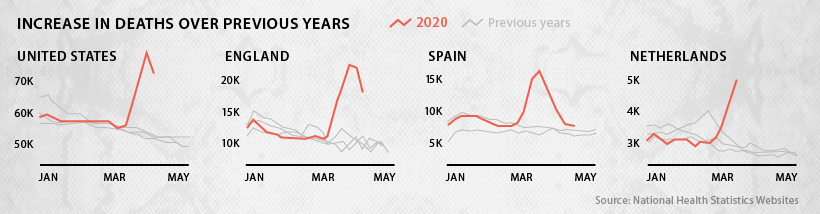

While these numbers help provide some context for the global scale of COVID-19 deaths, they do not offer a direct comparison. The fact is that many of the aforementioned death rates are based on much larger and consistent sample sizes of data. On the flipside, since WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020, daily confirmed deaths have fallen in a wide range between 272 and 10,520 per day—and there is no telling what could happen in the future. On top of this variance, data on confirmed COVID-19 deaths has other quirks. For example, testing rates for the virus may vary between jurisdictions, and there have also been disagreements between authorities on how deaths should even be tallied in the first place. This makes getting an accurate picture surprisingly complicated. While it’s impossible to know the true death toll of COVID-19, it is clear that in some countries daily deaths have reached rates 50% or higher than the historical average for periods of time:

Time, and further analysis, will be required to determine a more accurate COVID-19 death count. on Even while political regimes across these countries have changed over time, they’ve largely followed a few different types of governance. Today, every country can ultimately be classified into just nine broad forms of government systems. This map by Truman Du uses information from Wikipedia to map the government systems that rule the world today.

Countries By Type of Government

It’s important to note that this map charts government systems according to each country’s legal framework. Many countries have constitutions stating their de jure or legally recognized system of government, but their de facto or realized form of governance may be quite different. Here is a list of the stated government system of UN member states and observers as of January 2023: Let’s take a closer look at some of these systems.

Monarchies

Brought back into the spotlight after the death of Queen Elizabeth II of England in September 2022, this form of government has a single ruler. They carry titles from king and queen to sultan or emperor, and their government systems can be further divided into three modern types: constitutional, semi-constitutional, and absolute. A constitutional monarchy sees the monarch act as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, giving them little to no real power. For example, King Charles III is the head of 15 Commonwealth nations including Canada and Australia. However, each has their own head of government. On the other hand, a semi-constitutional monarchy lets the monarch or ruling royal family retain substantial political powers, as is the case in Jordan and Morocco. However, their monarchs still rule the country according to a democratic constitution and in concert with other institutions. Finally, an absolute monarchy is most like the monarchies of old, where the ruler has full power over governance, with modern examples including Saudi Arabia and Vatican City.

Republics

Unlike monarchies, the people hold the power in a republic government system, directly electing representatives to form government. Again, there are multiple types of modern republic governments: presidential, semi-presidential, and parliamentary. The presidential republic could be considered a direct progression from monarchies. This system has a strong and independent chief executive with extensive powers when it comes to domestic affairs and foreign policy. An example of this is the United States, where the President is both the head of state and the head of government. In a semi-presidential republic, the president is the head of state and has some executive powers that are independent of the legislature. However, the prime minister (or chancellor or equivalent title) is the head of government, responsible to the legislature along with the cabinet. Russia is a classic example of this type of government. The last type of republic system is parliamentary. In this system, the president is a figurehead, while the head of government holds real power and is validated by and accountable to the parliament. This type of system can be seen in Germany, Italy, and India and is akin to constitutional monarchies. It’s also important to point out that some parliamentary republic systems operate slightly differently. For example in South Africa, the president is both the head of state and government, but is elected directly by the legislature. This leaves them (and their ministries) potentially subject to parliamentary confidence.

One-Party State

Many of the systems above involve multiple political parties vying to rule and govern their respective countries. In a one-party state, also called a single-party state or single-party system, only one political party has the right to form government. All other political parties are either outlawed or only allowed limited participation in elections. In this system, a country’s head of state and head of government can be executive or ceremonial but political power is constitutionally linked to a single political movement. China is the most well-known example of this government system, with the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China ruling as the de facto leader since 1989.

Provisional

The final form of government is a provisional government formed as an interim or transitional government. In this system, an emergency governmental body is created to manage political transitions after the collapse of a government, or when a new state is formed. Often these evolve into fully constitutionalized systems, but sometimes they hold power for longer than expected. Some examples of countries that are considered provisional include Libya, Burkina Faso, and Chad.