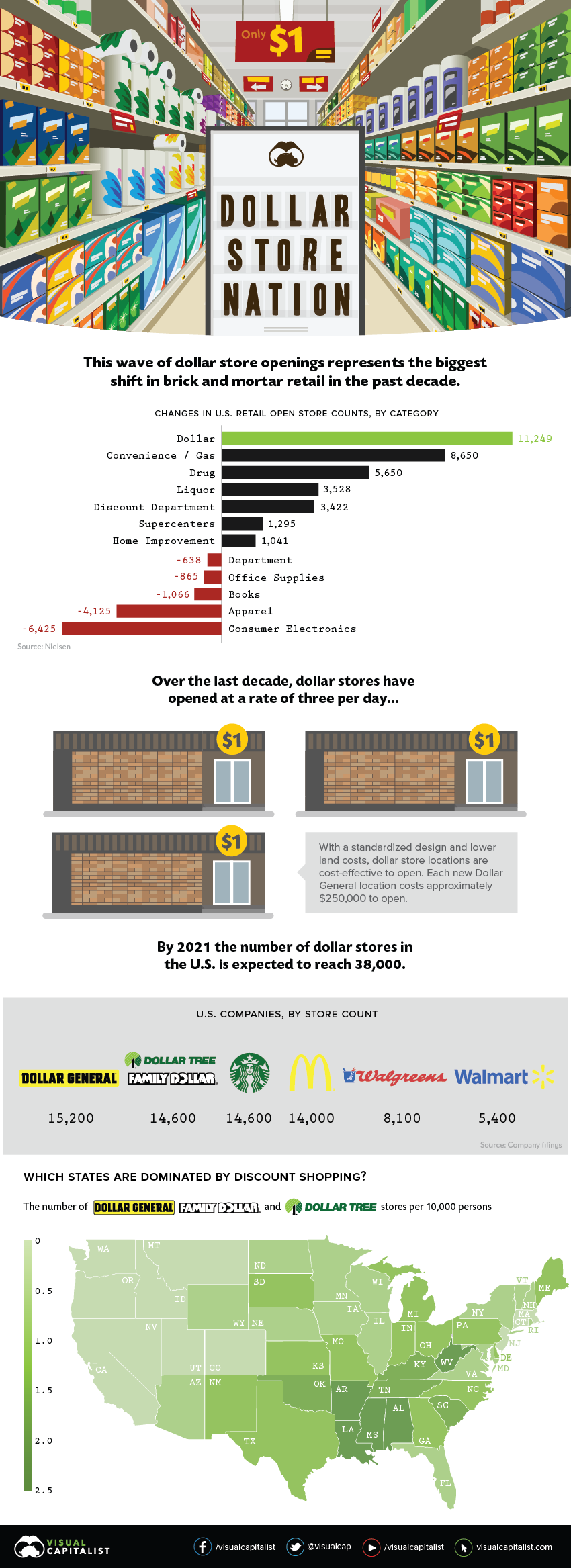

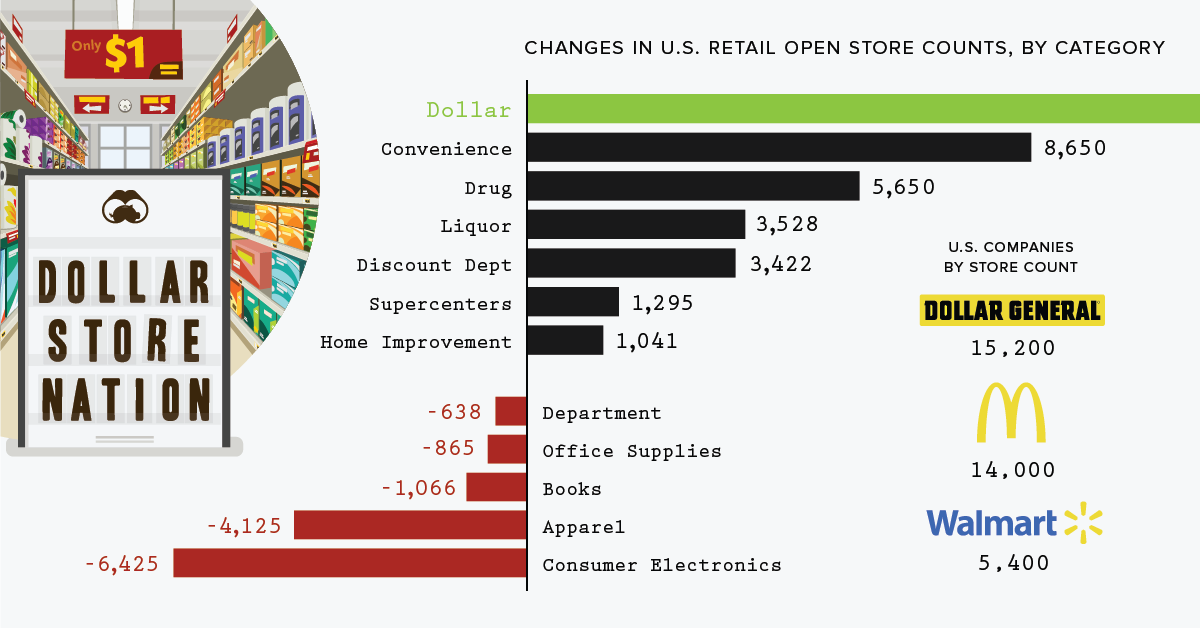

E-commerce is indisputably disrupting almost every imaginable aspect of retail, creating what has been coined as the “retail apocalypse”. As a result, certain segments of the market have had well publicized meltdowns – electronics and apparel, in particular – and the U.S. now has far more retail floor space available than any other nation. That said, there is one type of store that’s thriving in this unpredictable landscape – dollar stores. Today, we examine data from the Institute of Local Self-Reliance, which puts the scale of the United States’ dollar store boom into perspective.

Escaping the Retail Apocalypse

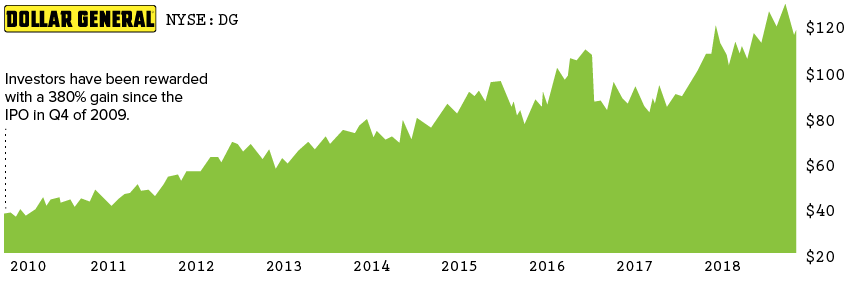

The persistent growth of dollar stores is the biggest retail trend in the past decade. Between 2007 and 2017, over 11,000 new dollar stores were opened; that’s roughly 93 new stores a month, or three per day. Dollar General, in particular, is reaping the rewards: the company has a market cap of over $30 billion.

Compared to mammoth retailer Walmart, Dollar General is the little store that could. Despite reporting lower sales per square foot, Dollar General outperforms Walmart in 5-year gross profit margins. This whopping difference in launching a new location contributes to the fast and furious spread of dollar stores. Dollar General and Dollar Tree (which now owns Family Dollar) boast 30,000 stores between them, eclipsing the six biggest U.S. retailers combined. Their combined annual sales also rival Apple Stores, including iTunes.

The Dollar Store Strategy

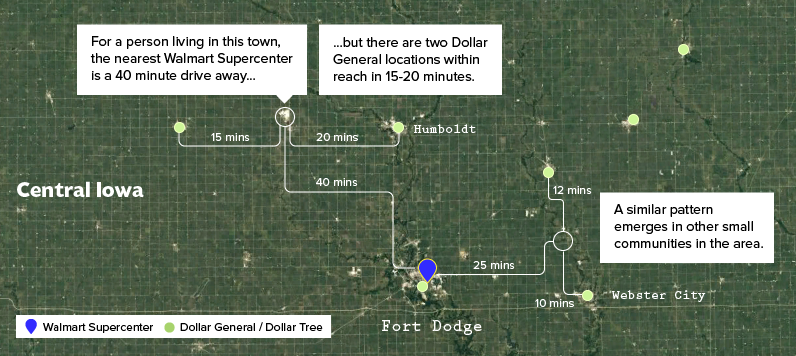

What makes dollar stores so lucrative? In a nutshell, they’re willing to go where others won’t. Dollar General focuses on rural areas, while Dollar Tree and Family Dollar are more prominent in urban and suburban areas. But they have one thing in common – all three chains target small towns in rural America, resulting in a high concentration per capita, especially in the South. – David Perdue, Former CEO of Dollar General Dollar General’s ambitious expansion into smaller towns has proven successful. Residents can find many everyday products at prices similar to those at Walmart, but without the longer drive to a Supercenter. Despite the 3,500 Walmart Supercenters spread out across the country, chances are, there’s a dollar store even closer.

Dollar stores fill a need in cash-strapped communities, saving time and gas money during a trip to the store, and then offering an affordable and enticing products inside the store itself.

America’s Grocery Gap

The no-frills shopping experience is also a quintessential trait of dollar stores. Dollar stores focus on a limited selection of private label goods, selling basics in small quantities instead of bulk. However, there’s also a dark underbelly to this trend. Dollar stores often enter areas with no grocery stores at all, called food deserts. In the absence of choice, dollar stores are welcomed with open arms – but the lack of fresh produce and abundance of processed, packaged foods leave much to be desired. — Stacy Mitchell, Institute for Local Self-Reliance On the other hand, when dollar stores compete with locally-owned grocery stores in the same area, sales in the latter can be cut by over 30% in some cases – taking an enormous toll on the community. The ILSR report suggests that dollar stores may not always be a by-product of economic distress, but a cause of it. Regardless of what perspective you have on the spread of dollar stores, it’s clear they’re here to stay. on These are in the form of Treasury securities, some of the most liquid assets worldwide. Central banks use them for foreign exchange reserves and private investors flock to them during flights to safety thanks to their perceived low default risk. Beyond these reasons, foreign investors may buy Treasuries as a store of value. They are often used as collateral during certain international trade transactions, or countries can use them to help manage exchange rate policy. For example, countries may buy Treasuries to protect their currency’s exchange rate from speculation. In the above graphic, we show the foreign holders of the U.S. national debt using data from the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

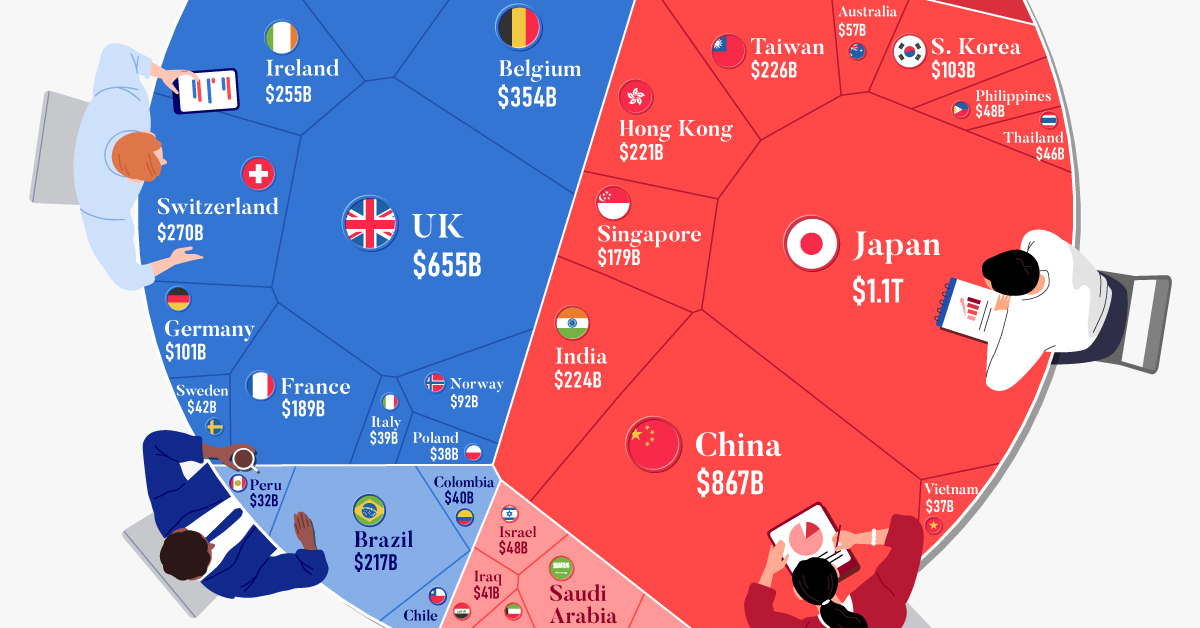

Top Foreign Holders of U.S. Debt

With $1.1 trillion in Treasury holdings, Japan is the largest foreign holder of U.S. debt. Japan surpassed China as the top holder in 2019 as China shed over $250 billion, or 30% of its holdings in four years. This bond offloading by China is the one way the country can manage the yuan’s exchange rate. This is because if it sells dollars, it can buy the yuan when the currency falls. At the same time, China doesn’t solely use the dollar to manage its currency—it now uses a basket of currencies. Here are the countries that hold the most U.S. debt: As the above table shows, the United Kingdom is the third highest holder, at over $655 billion in Treasuries. Across Europe, 13 countries are notable holders of these securities, the highest in any region, followed by Asia-Pacific at 11 different holders. A handful of small nations own a surprising amount of U.S. debt. With a population of 70,000, the Cayman Islands own a towering amount of Treasury bonds to the tune of $284 billion. There are more hedge funds domiciled in the Cayman Islands per capita than any other nation worldwide. In fact, the four smallest nations in the visualization above—Cayman Islands, Bermuda, Bahamas, and Luxembourg—have a combined population of just 1.2 million people, but own a staggering $741 billion in Treasuries.

Interest Rates and Treasury Market Dynamics

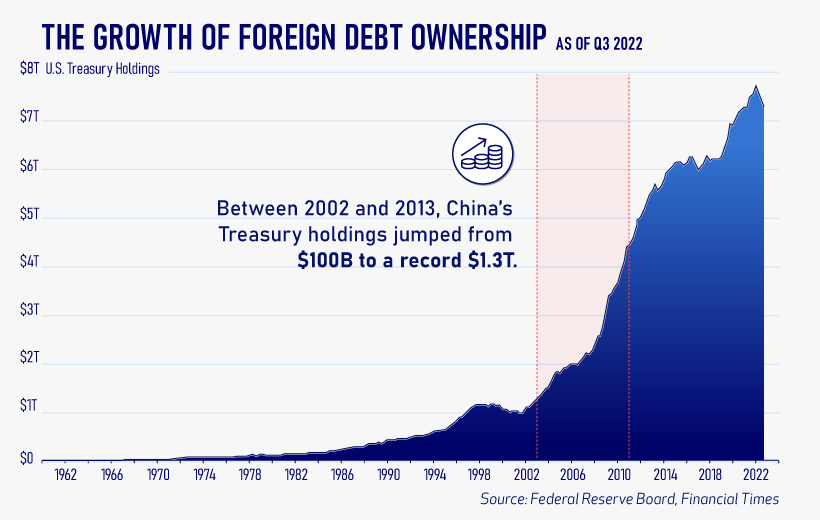

Over 2022, foreign demand for Treasuries sank 6% as higher interest rates and a strong U.S. dollar made owning these bonds less profitable. This is because rising interest rates on U.S. debt makes the present value of their future income payments lower. Meanwhile, their prices also fall. As the chart below shows, this drop in demand is a sharp reversal from 2018-2020, when demand jumped as interest rates hovered at historic lows. A similar trend took place in the decade after the 2008-09 financial crisis when U.S. debt holdings effectively tripled from $2 to $6 trillion.

Driving this trend was China’s rapid purchase of Treasuries, which ballooned from $100 billion in 2002 to a peak of $1.3 trillion in 2013. As the country’s exports and output expanded, it sold yuan and bought dollars to help alleviate exchange rate pressure on its currency. Fast-forward to today, and global interest-rate uncertainty—which in turn can impact national currency valuations and therefore demand for Treasuries—continues to be a factor impacting the future direction of foreign U.S. debt holdings.