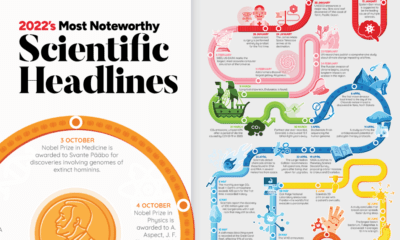

After a year of casualties, structural devastation, and innumerable headlines, the conflict drags on. Many report the impacts to the economy, social demographics, and international relationships, but how do science and academia fair in the throes of war? Within the actions and responses of the conflict, we take a look at how six key scenarios globally shape science.

War’s Material Impacts to Science

1. Russia Invades Ukraine

The assault to research infrastructure in Ukraine is devastating. Approximately 27% of buildings are damaged or destroyed. The country’s leading scientific research centers, like the Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology, or the world’s largest decameter-wavelength radio telescope, are in ruins. While the majority of research centers remain standing, many are not operating. Amidst rolling blackouts and disruptions, a dramatic decrease in research funds (as large as 50%) has cut back scientific activity in the country. Rebuilding efforts are underway, but the extent to which it will return to its former capacity remains to be seen.

2. Ukraine Fights Back

As research funds have been redirected to the military, and scientists, too, have pivoted in a similar way. Martial law and general mobilization have enlisted male researchers, especially those with military experience and those within the 18-60 age range. Women were exempt until July 2022. Those with degrees in chemistry, biology, and telecommunications were required to enter the military registry. For both men and women researchers alike, these requirements meant staying in the country for the remainder of the year. Extensions for mobilization have subsided as of February 19th, 2023.

Social Impacts of War to Science

3. Western Leaders Exclude Russia

One year ago, scientists and institutions around the world immediately launched into protest against Russia’s escalation:

The European Commission agreed to cease payments to Russian participants and to not renew contract agreements for Horizon Europe The $300-million, MIT-led Skoltech program was dissolved one day after the war began, with no foreseeable restart in the future Various governments and research councils in the European Union froze collaborations and discouraged working with Russian institutions The European Organization for Nuclear Research, CERN, barred all Russian observers and will dismiss almost 8% of its workers—about 1,000 Russian scientists—hen contracts expire later this year

These condemnations, and more, remain in effect today and are emboldened by what has come to be known as a “scientific boycott”. Journal publishers around the world imposed some of their own sanctions on Russian institutions and scientists in light of this boycott. These range from prohibiting Russian manuscript submissions (Elsevier’s Journal of Molecular Structure) to scrubbing journal indices of Russian papers and authors.

4. Russia Dissociates from the West

As a response to the sanctions imposed on the Russian economy, Russia ceases to sell natural gas to most of Europe. Institutions are reassessing their usage and dependence on Russian energy, but alternatives are not yet affordable. The German Electron Synchrotron (DESY) in Hamburg, home to the world’s most powerful X-ray laser, is struggling with rising electricity costs. CERN, for instance, has already cut its data collection for the year by two weeks in order to save money. This makes it difficult for pre-war projects to continue collaborating with Russia. As a result, there are questions about how withdrawals may be affecting Russian science, too. For now, that remains relatively unknown, though some have guesses. Young scientists, many barred from attending international conferences and meetings, may seek employment or opportunity elsewhere to develop their careers. Some speculate a “brain drain” effect may occur, similar to the academic fallout of the Soviet Union’s collapse in the 1990s. How Russia will participate in pre-war international research collaborations is still unknown. For now, a number of pre-war projects ranging from the Arctic to the fire-prone wilds of northern Russia are on hold. All of these scenarios paint a concerning picture about the progress of research. There are indications that Russian scientific collaboration may already be shifting eastward.

Philanthropic Impacts of War to Science

5. New Homes for Ukrainian Science

Finding support for Ukrainians emigrating from the conflict is difficult, but not impossible. Though many Ukrainians scientists remain in the country making the best of a difficult situation, approximately 6,000 are now living abroad. Most Ukrainian emigrants are now living in Poland and Germany. Some scientists continue to work remotely, supporting projects at their home institutions or with new research programs they’ve found since relocating. These success stories are thanks to the work of a number of ad-hoc mobilizations that help keep researchers working in the European cooperation. Groups like MSC4Ukraine help postdoc students and researchers find new opportunities across Europe. Social media trends like #Science4Ukraine help connect researchers to other supportive movements.

6. The International Rebuilding of Ukrainian Science

Various research institutions have also lent support to the survival and rebuilding of science in Ukraine:

The largest science prize, the Breakthrough Prize, recently donated $3 million to fund research programs and reconstruction efforts Federal research councils, like those in Netherlands and Switzerland, also have programs to formally support displaced scientists and researchers The European Union is investigating new funding schemes that could repurpose almost €320 billion of frozen Russian Federal Reserves

No Consensus on Boycott

While the Western front seems united in it’s condemnation of the war, the international science community isn’t in total agreement with a science boycott. Some scientists argue that excluding Russian scientists—especially those who have vocalized their disdain for the war—serves to punish unrelated individuals. This fractures the benefits of international scientific exchange. Others, especially those in countries who are economically dependent on Russia, have remained silent or even supported the invasion. In these cases, Russia’s science initiatives may lean more heavily in their direction. It’s easy to appreciate how war complicates many different angles of the global research ecosystem. After one year, how things will turn out remains a mystery. But one thing is for certain: science adapts and progresses even in the bleakest times. For now, supporting all efforts to reduce conflict remains in science’s best interests. Full sources here on Even while political regimes across these countries have changed over time, they’ve largely followed a few different types of governance. Today, every country can ultimately be classified into just nine broad forms of government systems. This map by Truman Du uses information from Wikipedia to map the government systems that rule the world today.

Countries By Type of Government

It’s important to note that this map charts government systems according to each country’s legal framework. Many countries have constitutions stating their de jure or legally recognized system of government, but their de facto or realized form of governance may be quite different. Here is a list of the stated government system of UN member states and observers as of January 2023: Let’s take a closer look at some of these systems.

Monarchies

Brought back into the spotlight after the death of Queen Elizabeth II of England in September 2022, this form of government has a single ruler. They carry titles from king and queen to sultan or emperor, and their government systems can be further divided into three modern types: constitutional, semi-constitutional, and absolute. A constitutional monarchy sees the monarch act as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, giving them little to no real power. For example, King Charles III is the head of 15 Commonwealth nations including Canada and Australia. However, each has their own head of government. On the other hand, a semi-constitutional monarchy lets the monarch or ruling royal family retain substantial political powers, as is the case in Jordan and Morocco. However, their monarchs still rule the country according to a democratic constitution and in concert with other institutions. Finally, an absolute monarchy is most like the monarchies of old, where the ruler has full power over governance, with modern examples including Saudi Arabia and Vatican City.

Republics

Unlike monarchies, the people hold the power in a republic government system, directly electing representatives to form government. Again, there are multiple types of modern republic governments: presidential, semi-presidential, and parliamentary. The presidential republic could be considered a direct progression from monarchies. This system has a strong and independent chief executive with extensive powers when it comes to domestic affairs and foreign policy. An example of this is the United States, where the President is both the head of state and the head of government. In a semi-presidential republic, the president is the head of state and has some executive powers that are independent of the legislature. However, the prime minister (or chancellor or equivalent title) is the head of government, responsible to the legislature along with the cabinet. Russia is a classic example of this type of government. The last type of republic system is parliamentary. In this system, the president is a figurehead, while the head of government holds real power and is validated by and accountable to the parliament. This type of system can be seen in Germany, Italy, and India and is akin to constitutional monarchies. It’s also important to point out that some parliamentary republic systems operate slightly differently. For example in South Africa, the president is both the head of state and government, but is elected directly by the legislature. This leaves them (and their ministries) potentially subject to parliamentary confidence.

One-Party State

Many of the systems above involve multiple political parties vying to rule and govern their respective countries. In a one-party state, also called a single-party state or single-party system, only one political party has the right to form government. All other political parties are either outlawed or only allowed limited participation in elections. In this system, a country’s head of state and head of government can be executive or ceremonial but political power is constitutionally linked to a single political movement. China is the most well-known example of this government system, with the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China ruling as the de facto leader since 1989.

Provisional

The final form of government is a provisional government formed as an interim or transitional government. In this system, an emergency governmental body is created to manage political transitions after the collapse of a government, or when a new state is formed. Often these evolve into fully constitutionalized systems, but sometimes they hold power for longer than expected. Some examples of countries that are considered provisional include Libya, Burkina Faso, and Chad.