Still, the forces underpinning each rise and fall are often less clear. Take the COVID-19 crash, for example. Despite lagging economic growth and historic unemployment levels, the S&P 500 bounced back 47% in just five months, in a stunning reversal. Drawing data from Macrotrends, the above infographic compares six historic market crashes—examining the length of their recoveries and the contextual factors influencing their durations.

The Big Picture

How does the current COVID-19 crash of 2020 stack up against previous market crashes? Price returns, based on nominal prices *Black Tuesday occurred about a month after the market peak on Oct 29, 1929 **The market hit a peak on Oct 13th, prior to Black Monday on Oct 19,1987 ***As of market close Aug 4, 2020 By far, the longest recovery of this list followed the devastation of Black Tuesday, while the shortest was Black Monday of 1987—where it took 19 months for the market to fully recover. Let’s take a closer look at each market crash to navigate the economic climate at the time.

After the Fall

What were some factors that can help provide context into the crash?

1929: Black Tuesday / Great Crash

Following Black Tuesday in 1929, the U.S. stock market took 7,256 days—equal to about 25 years—to fully recover from peak to peak. In response to the market crisis, a coalition of banks bought blocks of shares, but with negligible effects. In turn, investors fled the market. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve Board rose the discount lending rate to 6%. As a result, borrowing costs climbed for consumers, businesses, and the central banks themselves. The tightening of rates led to unintended consequences, with the economy capitulating into the Great Depression. Of course, factors that contributed to its prolonged recovery have been debated, but these are just a few of the actions that had implications at the time.

1973: Nixon Shock / OPEC Oil Embargo

The Nixon Shock corresponded with a series of economic measures in response to high inflation. Soaring inflation devastated stocks, consuming real returns on capital. Around the same time, the oil embargo also occurred, with OPEC member countries halting oil exports to the U.S. and its allies, causing a severe spike in oil prices. It took seven years for the S&P 500 to return to its previous peak.

1987: Black Monday

While the exact cause of the 1987 crash has been debated, key factors include both the advent of computerized trading systems and overvalued markets. To curtail the impact of the crash, former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan aggressively slashed interest rates, repeatedly promising to take great lengths to stabilize the market. The S&P took under two years to recover.

2000: Dot Com Bubble

To curb the stratospheric rise of U.S. tech stocks, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates five times in eight months, sending the markets into a tailspin. Virtually $5 trillion in market value evaporated.

2007: Global Financial Crisis

Relaxed credit policies, the proliferation of subprime mortgages, credit default swaps, and commercial mortgage-backed securities were all factors behind the market turmoil of 2007. As banks carved out risky loans packaged in opaque tranches of debt, risk in the market accelerated. Similar to 1987, the Federal Reserve initiated a number of rescue actions. Interest rates were brought down to historical levels and $498 billion in bailouts were injected into the financial system. Crisis-related bailouts extended to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), the Federal Housing Administration, and others.

2020: COVID-19 Crash

In 2020, historic fiscal stimulus measures along with trillions in Fed financing have factored heavily in its swift reversal. The result has been one of the steepest rallies in S&P 500 history. At the same time, the economy is mirroring Great Depression-level unemployment numbers, reaching 14.7% in April 2020. In short, this starkly exposes the sharp disconnect between the markets and broader economy.

Bearing Witness

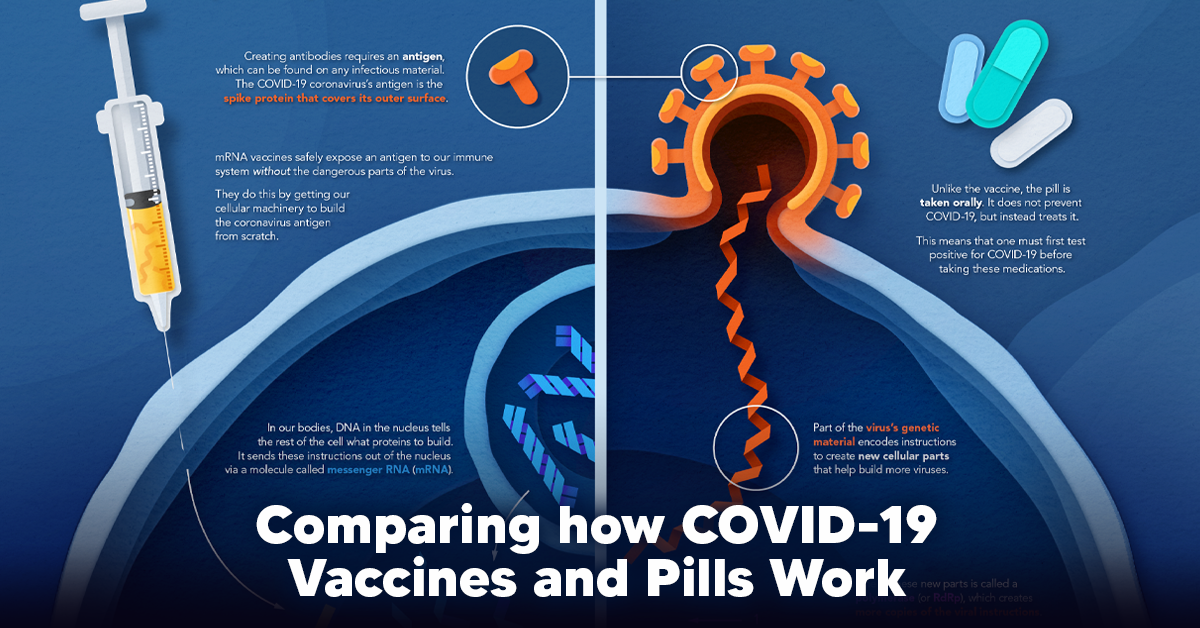

History offers many lessons, and in this case, a view into the shape of a post-coronavirus market recovery. Although the stock market is likely rallying off Fed liquidity, investor optimism, and the promise of potential vaccines, it’s interesting to note that the trajectory of this crash in some ways resembles the initial rebound shown during the Great Depression—which means we may not be out of the woods quite yet. As the S&P 500 edges 2% shy of its February peak, could the market post a hastened recovery—or is a protracted downturn in the cards? This graphic has been inspired by this Reddit post. on The leading options for preventing infection include social distancing, mask-wearing, and vaccination. They are still recommended during the upsurge of the coronavirus’s latest mutation, the Omicron variant. But in December 2021, The United States Food and Drug Administration (USDA) granted Emergency Use Authorization to two experimental pills for the treatment of new COVID-19 cases. These medications, one made by Pfizer and the other by Merck & Co., hope to contribute to the fight against the coronavirus and its variants. Alongside vaccinations, they may help to curb extreme cases of COVID-19 by reducing the need for hospitalization. Despite tackling the same disease, vaccines and pills work differently:

How a Vaccine Helps Prevent COVID-19

The main purpose of a vaccine is to prewarn the body of a potential COVID-19 infection by creating antibodies that target and destroy the coronavirus. In order to do this, the immune system needs an antigen. It’s difficult to do this risk-free since all antigens exist directly on a virus. Luckily, vaccines safely expose antigens to our immune systems without the dangerous parts of the virus. In the case of COVID-19, the coronavirus’s antigen is the spike protein that covers its outer surface. Vaccines inject antigen-building instructions* and use our own cellular machinery to build the coronavirus antigen from scratch. When exposed to the spike protein, the immune system begins to assemble antigen-specific antibodies. These antibodies wait for the opportunity to attack the real spike protein when a coronavirus enters the body. Since antibodies decrease over time, booster immunizations help to maintain a strong line of defense. *While different vaccine technologies exist, they all do a similar thing: introduce an antigen and build a stronger immune system.

How COVID Antiviral Pills Work

Antiviral pills, unlike vaccines, are not a preventative strategy. Instead, they treat an infected individual experiencing symptoms from the virus. Two drugs are now entering the market. Merck & Co.’s Lagevrio®, composed of one molecule, and Pfizer’s Paxlovid®, composed of two. These medications disrupt specific processes in the viral assembly line to choke the virus’s ability to replicate.

The Mechanism of Molnupiravir

RNA-dependent RNA Polymerase (RdRp) is a cellular component that works similar to a photocopying machine for the virus’s genetic instructions. An infected host cell is forced to produce RdRp, which starts generating more copies of the virus’s RNA. Molnupiravir, developed by Merck & Co., is a polymerase inhibitor. It inserts itself into the viral instructions that RdRp is copying, jumbling the contents. The RdRp then produces junk.

The Mechanism of Nirmatrelvir + Ritonavir

A replicating virus makes proteins necessary for its survival in a large, clumped mass called a polyprotein. A cellular component called a protease cuts a virus’s polyprotein into smaller, workable pieces. Pfizer’s antiviral medication is a protease inhibitor made of two pills: With a faulty polymerase or a large, unusable polyprotein, antiviral medications make it difficult for the coronavirus to replicate. If treated early enough, they can lessen the virus’s impact on the body.

The Future of COVID Antiviral Pills and Medications

Antiviral medications seem to have a bright future ahead of them. COVID-19 antivirals are based on early research done on coronaviruses from the 2002-04 SARS-CoV and the 2012 MERS-CoV outbreaks. Current breakthroughs in this technology may pave the way for better pharmaceuticals in the future. One half of Pfizer’s medication, ritonavir, currently treats many other viruses including HIV/AIDS. Gilead Science is currently developing oral derivatives of remdesivir, another polymerase inhibitor currently only offered to inpatients in the United States. More coronavirus antivirals are currently in the pipeline, offering a glimpse of control on the looming presence of COVID-19. Author’s Note: The medical information in this article is an information resource only, and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes. Please talk to your doctor before undergoing any treatment for COVID-19. If you become sick and believe you may have symptoms of COVID-19, please follow the CDC guidelines.