If this isn’t problematic enough, third parties can also take advantage of these biases to influence our thinking. The media, for example, can exploit our tendency to assign stereotypes to others by only providing catchy, surface-level information. Once established in our minds, these generalizations can be tough to shake off. Such tactics can have a powerful influence on public opinion if applied consistently to a broad audience. To help us avoid these mental pitfalls, today’s infographic from PredictIt lists common cognitive biases that influence the realm of politics, beginning with the “Big Cs”.

The First C: Confirmation Bias

People exhibit confirmation bias when they seek information that only affirms their pre-existing beliefs. This can cause them to become overly rigid in their political opinions, even when presented with conflicting ideas or evidence. When too many people fall victim to this bias, progress towards solving complex sociopolitical issues is thwarted. That’s because solving these issues in a bipartisan system requires cooperation from both sides of the spectrum. A reluctance towards establishing a common ground is already widespread in America. According to a 2019 survey, 70% of Democrats believed their party’s leaders should “stand up” to President Trump, even if less gets done in Washington. Conversely, 51% of Republicans believed that Trump should “stand up” to Democrats. In light of these developments, researchers have conducted studies to determine if the issue of confirmation bias is as prevalent as it seems. In one experiment, participants chose to either support or oppose a given sociopolitical issue. They were then presented with evidence that was conflicting, affirming, or a combination of both. In all scenarios, participants were most likely to stick with their initial decisions. Of those presented with conflicting evidence, just one in five changed their stance. Furthermore, participants who maintained their initial positions became even more confident in the superiority of their decision—a testament to how influential confirmation bias can be.

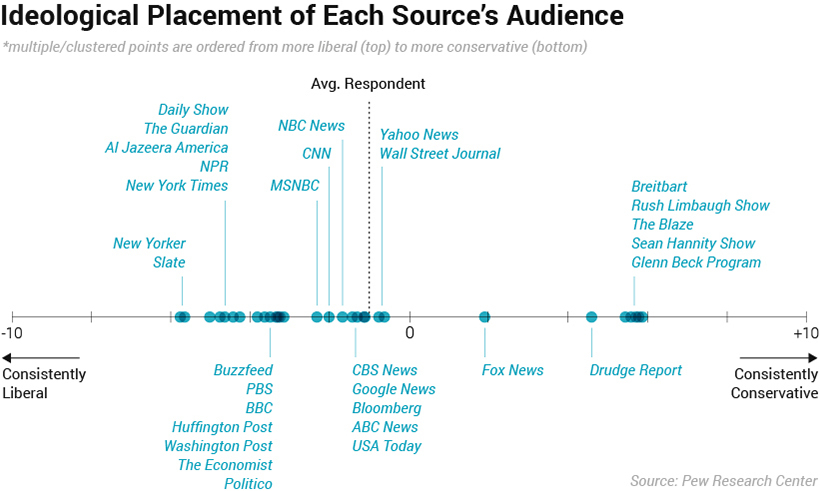

The Second C: Coverage Bias

Coverage bias, in the context of politics, is a form of media bias where certain politicians or topics are disproportionately covered. In some cases, media outlets can even twist stories to fit a certain narrative. For example, research from the University of South Florida analyzed media coverage on President Trump’s 2017 travel ban. It was discovered that primetime media hosts covered the ban through completely different perspectives. —Josepher, Bryce (2017) Charting the ideological placement of each source’s audience can help us gain a better understanding of the coverage bias at work. In other words, where do people on the left, middle, and right get their news?

The horizontal axis in this graphic corresponds to the Ideological Consistency Scale, which is composed of 10 questions. For each question, respondents are assigned a “-1” for a liberal response, “+1” for a conservative response, or a “0” for other responses. A summation of these scores places a respondent into one of five categories: Overcoming coverage bias—which dovetails into other biases like confirmation bias—may require us to follow a wider variety of sources, even those we may not initially agree with.

The Third C: Concision Bias

Concision bias is a type of bias where politicians or the media selectively focus on aspects of information that are easy to get across. In the process, more nuanced and delicate views get omitted from popular discourse. A common application of concision bias is the use of sound bites, which are short clips that can be taken out of a politician’s speech. When played in isolation, these clips may leave out important context for the audience. Without the proper context, multi-faceted issues can become extremely polarizing, and may be a reason for the growing partisan divide in America. In fact, there is less overlap in the political values of Republicans and Democrats than ever previously measured. In 1994, just 64% of Republicans were more conservative than the median Democrat. By 2017, that margin had grown considerably, to 95% of Republicans. The same trend can be found on the other end of the spectrum. Whereas 70% of Democrats were more liberal than the median Republican in 1994, this proportion increased to 97% by 2017.

Overcoming Our Biases

Achieving full self-awareness can be difficult, especially when new biases emerge in our constantly evolving world. So where do we begin? Simply remembering these mental pitfalls exist can be a great start—after all, we can’t fix what we don’t know. Individuals concerned about the upcoming presidential election may find it useful to focus their attention on the Big Cs, as these biases can play a significant role in shaping political beliefs. Maintaining an open mindset and diversifying the media sources we follow are two tactics that may act as a hedge. on Even while political regimes across these countries have changed over time, they’ve largely followed a few different types of governance. Today, every country can ultimately be classified into just nine broad forms of government systems. This map by Truman Du uses information from Wikipedia to map the government systems that rule the world today.

Countries By Type of Government

It’s important to note that this map charts government systems according to each country’s legal framework. Many countries have constitutions stating their de jure or legally recognized system of government, but their de facto or realized form of governance may be quite different. Here is a list of the stated government system of UN member states and observers as of January 2023: Let’s take a closer look at some of these systems.

Monarchies

Brought back into the spotlight after the death of Queen Elizabeth II of England in September 2022, this form of government has a single ruler. They carry titles from king and queen to sultan or emperor, and their government systems can be further divided into three modern types: constitutional, semi-constitutional, and absolute. A constitutional monarchy sees the monarch act as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, giving them little to no real power. For example, King Charles III is the head of 15 Commonwealth nations including Canada and Australia. However, each has their own head of government. On the other hand, a semi-constitutional monarchy lets the monarch or ruling royal family retain substantial political powers, as is the case in Jordan and Morocco. However, their monarchs still rule the country according to a democratic constitution and in concert with other institutions. Finally, an absolute monarchy is most like the monarchies of old, where the ruler has full power over governance, with modern examples including Saudi Arabia and Vatican City.

Republics

Unlike monarchies, the people hold the power in a republic government system, directly electing representatives to form government. Again, there are multiple types of modern republic governments: presidential, semi-presidential, and parliamentary. The presidential republic could be considered a direct progression from monarchies. This system has a strong and independent chief executive with extensive powers when it comes to domestic affairs and foreign policy. An example of this is the United States, where the President is both the head of state and the head of government. In a semi-presidential republic, the president is the head of state and has some executive powers that are independent of the legislature. However, the prime minister (or chancellor or equivalent title) is the head of government, responsible to the legislature along with the cabinet. Russia is a classic example of this type of government. The last type of republic system is parliamentary. In this system, the president is a figurehead, while the head of government holds real power and is validated by and accountable to the parliament. This type of system can be seen in Germany, Italy, and India and is akin to constitutional monarchies. It’s also important to point out that some parliamentary republic systems operate slightly differently. For example in South Africa, the president is both the head of state and government, but is elected directly by the legislature. This leaves them (and their ministries) potentially subject to parliamentary confidence.

One-Party State

Many of the systems above involve multiple political parties vying to rule and govern their respective countries. In a one-party state, also called a single-party state or single-party system, only one political party has the right to form government. All other political parties are either outlawed or only allowed limited participation in elections. In this system, a country’s head of state and head of government can be executive or ceremonial but political power is constitutionally linked to a single political movement. China is the most well-known example of this government system, with the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China ruling as the de facto leader since 1989.

Provisional

The final form of government is a provisional government formed as an interim or transitional government. In this system, an emergency governmental body is created to manage political transitions after the collapse of a government, or when a new state is formed. Often these evolve into fully constitutionalized systems, but sometimes they hold power for longer than expected. Some examples of countries that are considered provisional include Libya, Burkina Faso, and Chad.