History is full of trade wars. In the majority of cases, the consequences are mostly economic – trade barriers are enacted, and then retaliatory measures are used to counter. Relations can continue to escalate until an understanding can be reached by both parties. In the minority of cases, trade wars can lead to world-changing consequences. You may remember that the Boston Tea Party of 1773 was a bold response to an unfair trade measure imposed by a ruling power, and it proved to be a key catalyst that led to the American Revolution. Meanwhile, the Opium Wars occurred after the Qing Dynasty (China) tried to prevent British merchants from selling opium to the Chinese in the 1830s. These trade barriers led to armed conflicts, and effectively put the nail in the coffin of the Qing Dyasty – the start of China’s infamous “century of humiliation”.

U.S. Trade Wars

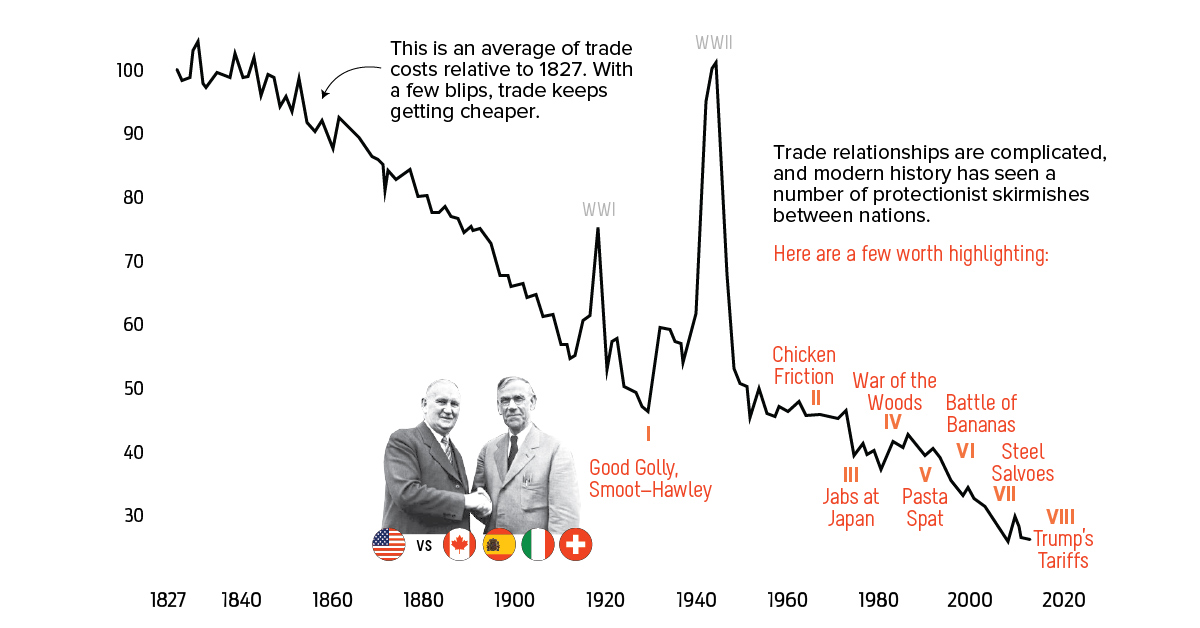

Today’s chart pulls together details on some of the biggest trade conflicts in modern U.S. history. Here are some of the more interesting U.S. trade wars, and how they compare to the current spat that is evolving with major trade partners:

- Smoot-Hawley, 1930 Imposed during The Great Depression, the Smoot-Hawley Act is almost universally recognized by economists and economic historians as triggering a trade war that exacerbated the recovery.

- Chicken Friction, 1963 Factory farming of chicken in the U.S. ended up catching European farmers off guard. French and German authorities responded by imposing tariffs, and the U.S. then taxed imports such as trucks and brandy.

- Jabs at Japan, 1981 Japan’s mid-century rise led to the country becoming an export powerhouse. As Japanese cars flooded the U.S. market, intense pressure eventually led to the signing of a Voluntary Export Restraint (VER) agreement that limited sales in the United States. During this same timeframe, the two countries also squabbled about other goods like electronics, motorcycles, and semiconductors.

- War of the Woods, 1982 The Canada-U.S. Softwood Lumber dispute kicked off in 1982, but it inevitably resurfaces in the news every few years.

- Pasta Spat, 1985 The U.S. was displeased with the level of access for citrus products in Europe, and put a tariff on pasta products. Europe retaliated by taxing walnuts and lemons from the States.

- Battle of the Bananas, 1993 Another agricultural trade war, the Battle of the Bananas occurred after Europe slapped tariffs on the import of Latin American bananas. Many of these companies, owned by Americans, were not impressed. In response, there were eight separate complaints filed to the World Trade Organization (WTO). They weren’t resolved until 2012.

- Steel Salvoes, 2002 These were the last major U.S. steel tariffs introduced before the more recent ones. The goal was similar: to revive the steel industry in the country. However, after a period of brief stability, jobs continued to decline. The European Union responded by taxing oranges exported from Florida. on Both figures surpassed analyst expectations by a wide margin, and in January, the unemployment rate hit a 53-year low of 3.4%. With the recent release of February’s numbers, unemployment is now reported at a slightly higher 3.6%. A low unemployment rate is a classic sign of a strong economy. However, as this visualization shows, unemployment often reaches a cyclical low point right before a recession materializes.

Reasons for the Trend

In an interview regarding the January jobs data, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made a bold statement: While there’s nothing wrong with this assessment, the trend we’ve highlighted suggests that Yellen may need to backtrack in the near future. So why do recessions tend to begin after unemployment bottoms out?

The Economic Cycle

The economic cycle refers to the economy’s natural tendency to fluctuate between periods of growth and recession. This can be thought of similarly to the four seasons in a year. An economy expands (spring), reaches a peak (summer), begins to contract (fall), then hits a trough (winter). With this in mind, it’s reasonable to assume that a cyclical low in the unemployment rate (peak employment) is simply a sign that the economy has reached a high point.

Monetary Policy

During periods of low unemployment, employers may have a harder time finding workers. This forces them to offer higher wages, which can contribute to inflation. For context, consider the labor shortage that emerged following the COVID-19 pandemic. We can see that U.S. wage growth (represented by a three-month moving average) has climbed substantially, and has held above 6% since March 2022. The Federal Reserve, whose mandate is to ensure price stability, will take measures to prevent inflation from climbing too far. In practice, this involves raising interest rates, which makes borrowing more expensive and dampens economic activity. Companies are less likely to expand, reducing investment and cutting jobs. Consumers, on the other hand, reduce the amount of large purchases they make. Because of these reactions, some believe that aggressive rate hikes by the Fed can either cause a recession, or make them worse. This is supported by recent research, which found that since 1950, central banks have been unable to slow inflation without a recession occurring shortly after.

Politicians Clash With Economists

The Fed has raised interest rates at an unprecedented pace since March 2022 to combat high inflation. More recently, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell warned that interest rates could be raised even higher than originally expected if inflation continues above target. Senator Elizabeth Warren expressed concern that this would cost Americans their jobs, and ultimately, cause a recession. Powell remains committed to bringing down inflation, but with the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, some analysts believe there could be a pause coming in interest rate hikes. Editor’s note: just after publication of this article, it was confirmed that U.S. interest rates were hiked by 25 basis points (bps) by the Federal Reserve.