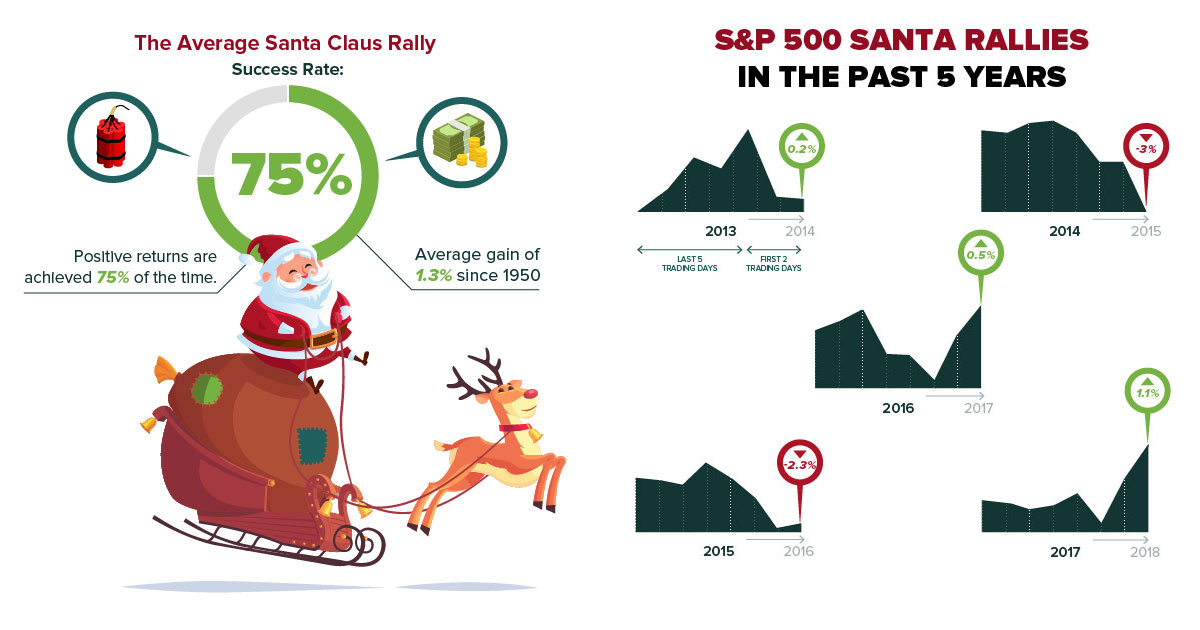

Just like children eagerly anticipate the arrival of the big man in the red suit, stock traders have a similar holiday tradition of importance. According to the 2019 Stock Trader’s Almanac, there’s an average 1.3% market rally in stocks that occurs every year during the holidays. Dubbed the “Santa Claus Rally”, it’s happened about 75% of the time since 1969. And this year in particular, after one of the worst months for the market in recent memory, it’s no secret that investors have their hopes up for a sizable present under the tree.

Recent Rally History

Although the Santa Claus Rally has historical significance going back many decades, over the more recent period it’s been much more elusive. Here is the data over the last five years. We’re using the time period as defined by the Trader’s Almanac (last five trading days of December, and first two in New Year), and S&P 500 Index prices.

As you can see, Santa provided a nice gift to traders (1.1%) last year – but in two of the previous holidays stretches, Wall Street must have been far naughtier. During the 2014-15 and 2015-16 seasons, the S&P 500 saw -2.7% returns, a proverbial lump of coal in portfolio stockings.

Do You Believe?

No one is really sure why the Santa Claus Rally happens, but various theories have been proposed. Some say investors are buying in anticipation of the January effect, or that it happens as a result of tax reasons. Others say it’s a period of time where institutional investors are home with their families, and bullish retail investors take control of the market. Either way, it seems after a brutal December – which included the worst week for the Dow (-7%) since the financial crisis – the market could benefit from the Santa bump this year. At time of publication (Dec. 28th, 4pm ET), the S&P 500 is up 5.7% from Christmas Eve lows – though there are still a few days left in the typical rally time window to see if the gains hold. on These are in the form of Treasury securities, some of the most liquid assets worldwide. Central banks use them for foreign exchange reserves and private investors flock to them during flights to safety thanks to their perceived low default risk. Beyond these reasons, foreign investors may buy Treasuries as a store of value. They are often used as collateral during certain international trade transactions, or countries can use them to help manage exchange rate policy. For example, countries may buy Treasuries to protect their currency’s exchange rate from speculation. In the above graphic, we show the foreign holders of the U.S. national debt using data from the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Top Foreign Holders of U.S. Debt

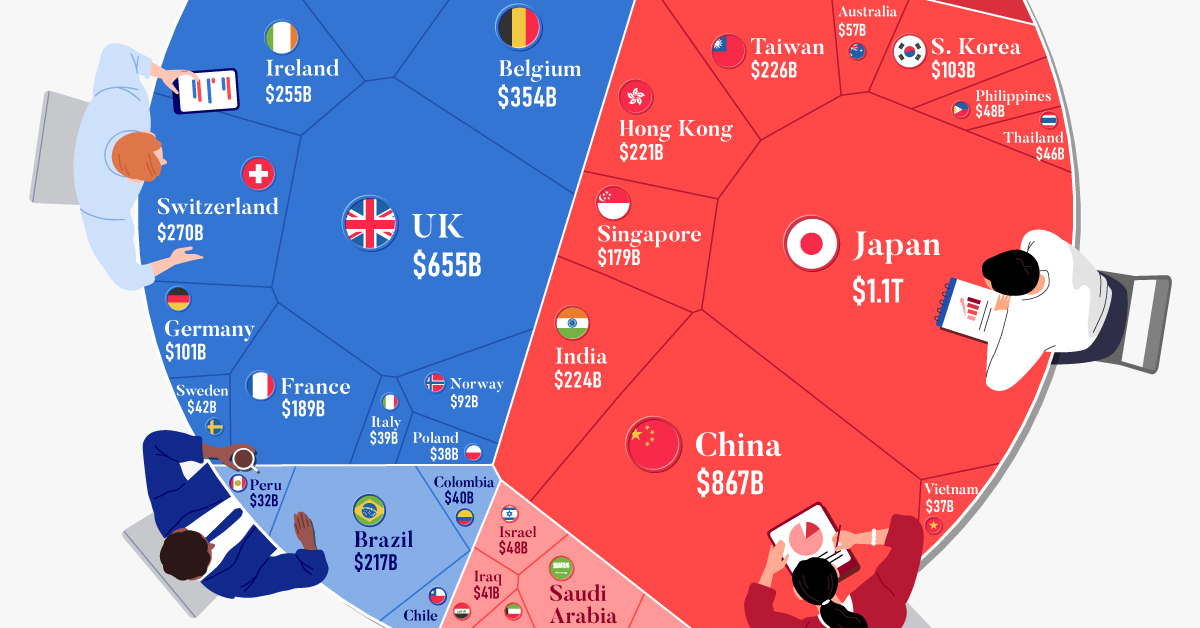

With $1.1 trillion in Treasury holdings, Japan is the largest foreign holder of U.S. debt. Japan surpassed China as the top holder in 2019 as China shed over $250 billion, or 30% of its holdings in four years. This bond offloading by China is the one way the country can manage the yuan’s exchange rate. This is because if it sells dollars, it can buy the yuan when the currency falls. At the same time, China doesn’t solely use the dollar to manage its currency—it now uses a basket of currencies. Here are the countries that hold the most U.S. debt: As the above table shows, the United Kingdom is the third highest holder, at over $655 billion in Treasuries. Across Europe, 13 countries are notable holders of these securities, the highest in any region, followed by Asia-Pacific at 11 different holders. A handful of small nations own a surprising amount of U.S. debt. With a population of 70,000, the Cayman Islands own a towering amount of Treasury bonds to the tune of $284 billion. There are more hedge funds domiciled in the Cayman Islands per capita than any other nation worldwide. In fact, the four smallest nations in the visualization above—Cayman Islands, Bermuda, Bahamas, and Luxembourg—have a combined population of just 1.2 million people, but own a staggering $741 billion in Treasuries.

Interest Rates and Treasury Market Dynamics

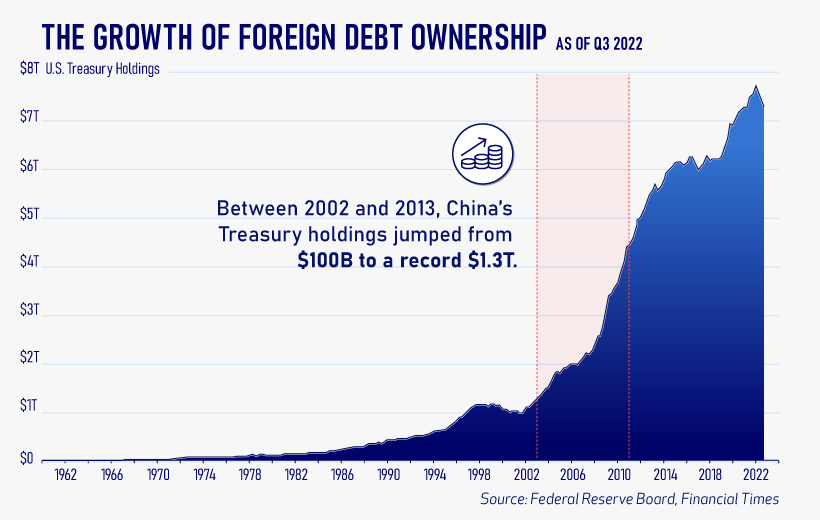

Over 2022, foreign demand for Treasuries sank 6% as higher interest rates and a strong U.S. dollar made owning these bonds less profitable. This is because rising interest rates on U.S. debt makes the present value of their future income payments lower. Meanwhile, their prices also fall. As the chart below shows, this drop in demand is a sharp reversal from 2018-2020, when demand jumped as interest rates hovered at historic lows. A similar trend took place in the decade after the 2008-09 financial crisis when U.S. debt holdings effectively tripled from $2 to $6 trillion.

Driving this trend was China’s rapid purchase of Treasuries, which ballooned from $100 billion in 2002 to a peak of $1.3 trillion in 2013. As the country’s exports and output expanded, it sold yuan and bought dollars to help alleviate exchange rate pressure on its currency. Fast-forward to today, and global interest-rate uncertainty—which in turn can impact national currency valuations and therefore demand for Treasuries—continues to be a factor impacting the future direction of foreign U.S. debt holdings.