Presented by: Nevada Energy Metals, eCobalt Solutions Inc., and Great Lakes Graphite

Explaining the Surging Demand for Lithium-Ion Batteries

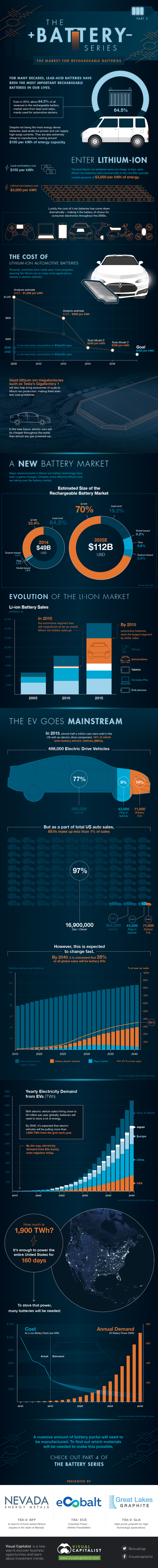

In Parts 1 and 2, we examined the evolution of battery technology as well as what batteries can and cannot do. In this part, we will tackle demand in the rechargeable battery market, with a major focus on the rapidly growing lithium-ion segment. For many decades, lead-acid batteries have been the most important rechargeable batteries in our lives. Even in 2014, about 64.5% of all revenues in the rechargeable battery market were from lead-acid sales, mainly to be used for automotive starters. Why? Despite not being the most energy dense batteries, lead-acids are proven and can supply high surge currents. They are also extremely cheap to manufacture, costing around $150 per kWh of energy capacity.

Enter Lithium-Ion

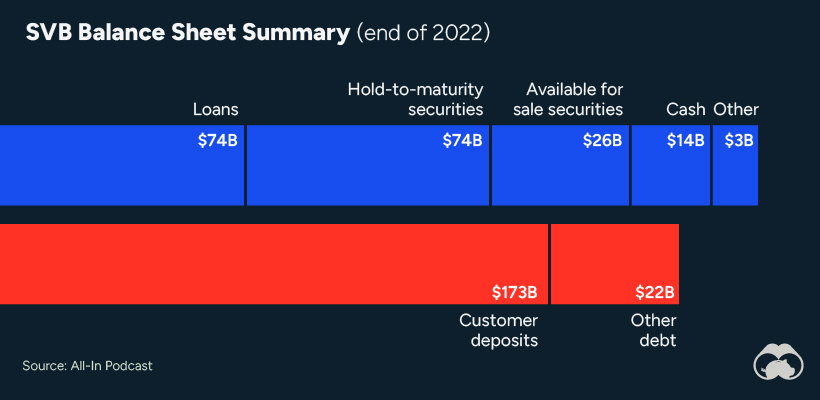

The first lithium-ions were not cheap. In fact, early batteries produced commercially in the mid-90s typically costed upwards of $3,000 per kWh of energy. Luckily, the cost of lithium-ion batteries has come down dramatically, making it the battery of choice for consumer electronics throughout the 2000s. And recently, scientists have made even more progress, opening the lithium-ion to many more applications, namely in electric vehicles. In 2008, analysts estimated that lithium-ion battery packs costed $600-$1,200 per kWh, but this range would drop to $500-800 per kWh over the following four years. Tesla now claims that a Tesla Model S battery cost is $240 per kWh and that the expected cost for a Model 3 is $190 per kWh. At $240 kWh, lithium-ions become competitive with $3/gallon gas. At $150, they are even competitive with $2 gas. Giant megafactories such as Tesla’s Gigafactory 1 will also help bring economies of scale to lithium-ion production, making them even less cost-prohibitive. Soon battery packs will cost closer to $100 per kWh, which will make them essentially cheaper than all gas-powered vehicles.

Demand for Lithium-Ion Batteries

Major advancements in lithium-ion battery technology have been a game-changer. Cheaper, more-effective lithium-ions are now taking over the battery market. In 2014, lithium-ions made up 33.4% of the rechargeable battery market worldwide, worth $49 billion. By 2025, it is estimated by Bernstein that the rechargeable battery market will more than double in size to $112 billion, while lithium-ion’s market share will more than double to 70.0%. The key driver? The automotive segment. In 2010, the automotive sector was a drop in the bucket for lithium-ion battery sales. Five years later, automotive made up more than $5 billion of sales in a sector worth nearly $16 billion.

The EV Goes Mainstream

In 2015, almost half a million cars were sold in the US with an electric drive component. 14% of these sales were battery electric vehicles (BEVs):

71,000 Battery EVs (14%) 43,000 plug-in hybrids (9%) 384,000 hybrids (77%)

= 498,000 electric drive vehicles But as a part of total US auto sales, BEVs still made up less than 1% of sales:

71,000 battery EVs (0.4%) 43,000 plug-in hybrids (0.3%) 384,000 hybrids (2.3%) 16,900,000 gas/diesel sales (97%)

However, in the near future, this is expected to change fast. By 2040, approximately 35% of all global sales will be BEVs. This will put electric vehicle sales at close to 40 million per year globally, meaning a lot of energy will need to be stored by batteries. Bloomberg New Energy Finance expects that at this point, that electric vehicles will be pulling more than 1,900 TWh from the grid each year. How much is 1,900 TWh? It’s enough to power the entire United States for 160 days. And to meet this demand for lithium-ion powered vehicles, a massive amount of battery packs will need to be manufactured. Part 4 of The Battery Series looks at which materials will be needed to make this possible.

on But fast forward to the end of last week, and SVB was shuttered by regulators after a panic-induced bank run. So, how exactly did this happen? We dig in below.

Road to a Bank Run

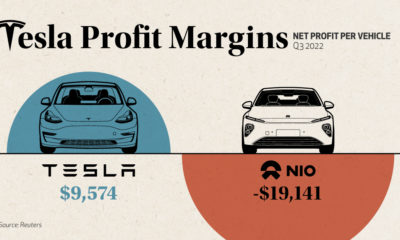

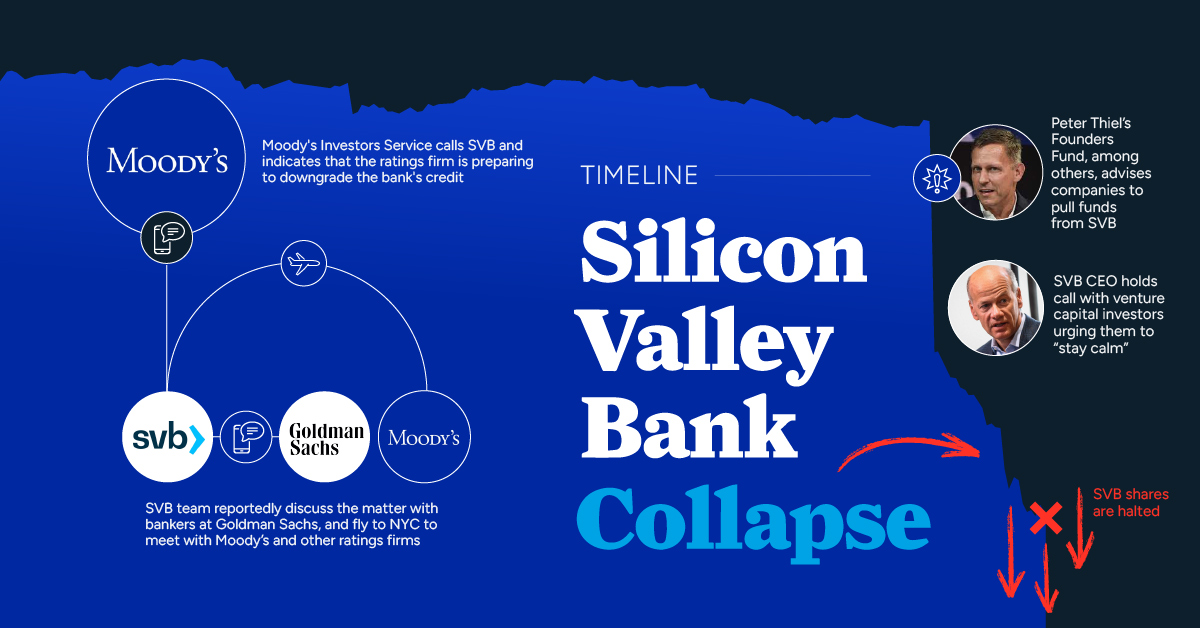

SVB and its customers generally thrived during the low interest rate era, but as rates rose, SVB found itself more exposed to risk than a typical bank. Even so, at the end of 2022, the bank’s balance sheet showed no cause for alarm.

As well, the bank was viewed positively in a number of places. Most Wall Street analyst ratings were overwhelmingly positive on the bank’s stock, and Forbes had just added the bank to its Financial All-Stars list. Outward signs of trouble emerged on Wednesday, March 8th, when SVB surprised investors with news that the bank needed to raise more than $2 billion to shore up its balance sheet. The reaction from prominent venture capitalists was not positive, with Coatue Management, Union Square Ventures, and Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund moving to limit exposure to the 40-year-old bank. The influence of these firms is believed to have added fuel to the fire, and a bank run ensued. Also influencing decision making was the fact that SVB had the highest percentage of uninsured domestic deposits of all big banks. These totaled nearly $152 billion, or about 97% of all deposits. By the end of the day, customers had tried to withdraw $42 billion in deposits.

What Triggered the SVB Collapse?

While the collapse of SVB took place over the course of 44 hours, its roots trace back to the early pandemic years. In 2021, U.S. venture capital-backed companies raised a record $330 billion—double the amount seen in 2020. At the time, interest rates were at rock-bottom levels to help buoy the economy. Matt Levine sums up the situation well: “When interest rates are low everywhere, a dollar in 20 years is about as good as a dollar today, so a startup whose business model is “we will lose money for a decade building artificial intelligence, and then rake in lots of money in the far future” sounds pretty good. When interest rates are higher, a dollar today is better than a dollar tomorrow, so investors want cash flows. When interest rates were low for a long time, and suddenly become high, all the money that was rushing to your customers is suddenly cut off.” Source: Pitchbook Why is this important? During this time, SVB received billions of dollars from these venture-backed clients. In one year alone, their deposits increased 100%. They took these funds and invested them in longer-term bonds. As a result, this created a dangerous trap as the company expected rates would remain low. During this time, SVB invested in bonds at the top of the market. As interest rates rose higher and bond prices declined, SVB started taking major losses on their long-term bond holdings.

Losses Fueling a Liquidity Crunch

When SVB reported its fourth quarter results in early 2023, Moody’s Investor Service, a credit rating agency took notice. In early March, it said that SVB was at high risk for a downgrade due to its significant unrealized losses. In response, SVB looked to sell $2 billion of its investments at a loss to help boost liquidity for its struggling balance sheet. Soon, more hedge funds and venture investors realized SVB could be on thin ice. Depositors withdrew funds in droves, spurring a liquidity squeeze and prompting California regulators and the FDIC to step in and shut down the bank.

What Happens Now?

While much of SVB’s activity was focused on the tech sector, the bank’s shocking collapse has rattled a financial sector that is already on edge.

The four biggest U.S. banks lost a combined $52 billion the day before the SVB collapse. On Friday, other banking stocks saw double-digit drops, including Signature Bank (-23%), First Republic (-15%), and Silvergate Capital (-11%).

Source: Morningstar Direct. *Represents March 9 data, trading halted on March 10.

When the dust settles, it’s hard to predict the ripple effects that will emerge from this dramatic event. For investors, the Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen announced confidence in the banking system remaining resilient, noting that regulators have the proper tools in response to the issue.

But others have seen trouble brewing as far back as 2020 (or earlier) when commercial banking assets were skyrocketing and banks were buying bonds when rates were low.