Enter vertical farming – the idea of building entire skyscrapers occupied with vertically-stacked farms that produce crops twice as fast, while using 40% less power, having 80% less food waste, and using 99% less water than outdoor fields. Is it feasible, or is it a futuristic money pit?

The Advantages of Vertical Farming

There’s no question that vertical farming has enticing potential benefits. The first is yield. Vertical farming can produce crops year-round, which increases production efficiency by a multiplier of 4 to 6 depending on the crop. There would also be less wastage and spoilage, as most of the crops could be sold fresh in a market or restaurant from the same facility. It’s estimated that 30% of harvested crops today are lost due to spoilage or infestation. Secondly, vertical farming has less risk associated with it. Big weather events such as floods, droughts, or storms can put a dent into agricultural activity fast, costing farmers billions of dollars. Farming indoors can reduce the risk of these types of events to as low as possible. Lastly, vertical farming is inherently more sustainable. By stacking farms vertically, the productivity per unit of land can be many times higher and arable land can be saved for other purposes. Further, there are no transportation costs to get the crops to market, and energy and water can be recycled within the building. Methane digesters can even help convert organic waste to energy to help power the building. On paper, vertical farming seems to have big advantages.

Too Good to be True?

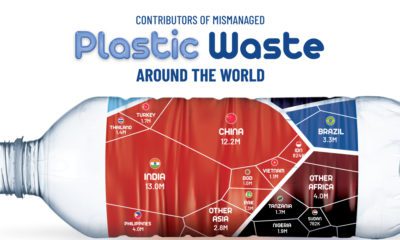

Critics of vertical farming question the potential profitability of commercial operations. They say the capital expenditures, as well as the additional energy costs for lighting and heating, could outweigh any benefits. Building complex plumbing and elevator systems to distribute food and water throughout a 30-story building is not easy. Meanwhile, for traditional farming operations, both sunlight and heat are free. Irrigation is generally cheap as well. The benefits of vertically-stacked farms would have to outweigh the increased costs. With billions of new people being added to cities over the next decades, this could come be sooner than later. Original graphic by: Futurism on In fact, many pieces of ocean plastic waste have come together to create a vortex of plastic waste thrice the size of France in the Pacific Ocean between California and Hawaii. Where does all of this plastic come from? In this graphic, Louis Lugas Wicaksono used data from a research paper by Lourens J.J. Meijer and team to highlight the top 10 countries emitting plastic pollutants in the waters surrounding them.

Plastic’s Ocean Voyage

First, let’s talk about how this plastic waste reaches the oceans in the first place. Most of the plastic waste found in the deep blue waters comes from the litter in parks, beaches, or along the storm drains lining our streets. These bits of plastic waste are carried into our drains, streams, and rivers by wind and rainwater runoff. The rivers then turn into plastic superhighways, transporting the plastic to the oceans. A large additional chunk of ocean plastic comes from damaged fishing nets or ghost nets that are directly discarded into the high seas.

Countries Feeding the Plastic Problem

Some might think that the countries producing or consuming the most plastic are the ones that pollute the oceans the most. But that’s not true. According to the study, countries with a smaller geographical area, longer coastlines, high rainfall, and poor waste management systems are more likely to wash plastics into the sea. For example, China generates 10 times the plastic waste that Malaysia does. However, 9% of Malaysia’s total plastic waste is estimated to reach the ocean, in comparison to China’s 0.6%. The Philippines—an archipelago of over 7,000 islands, with a 36,289 kilometer coastline and 4,820 plastic emitting rivers—is estimated to emit 35% of the ocean’s plastic. In addition to the Philippines, over 75% of the accumulated plastic in the ocean is reported to come from the mismanaged waste in Asian countries including India, Malaysia, China, Indonesia, Myanmar, Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Thailand.

The Path to a Plastic-free Ocean

The first, and most obvious, way to reduce plastic accumulation is to reduce the use of plastic. Lesser production equals lesser waste. The second step is managing the plastic waste generated, and this is where the challenge lies. Many high-income countries generate high amounts of plastic waste, but are either better at processing it or exporting it to other countries. Meanwhile, many of the middle-income and low-income countries that both demand plastics and receive bulk exports have yet to develop the infrastructure needed to process it.