As many as 80-90% of startups fold and those left standing also fail, repeatedly. Rarely does a business take a straight run at success, and that includes the likes of Apple, Facebook, and their fellow tech giants. Product lines can come to a screeching halt. Ideas can be stolen. And, yes, even geniuses like Steve Jobs get forced out. But by embracing uncertainty and making timely pivots, the tech companies in the infographic above have become some of the most influential—and valuable—organizations on the planet. Let’s take a closer look at some of tech’s intriguing beginnings and lucrative pivots.

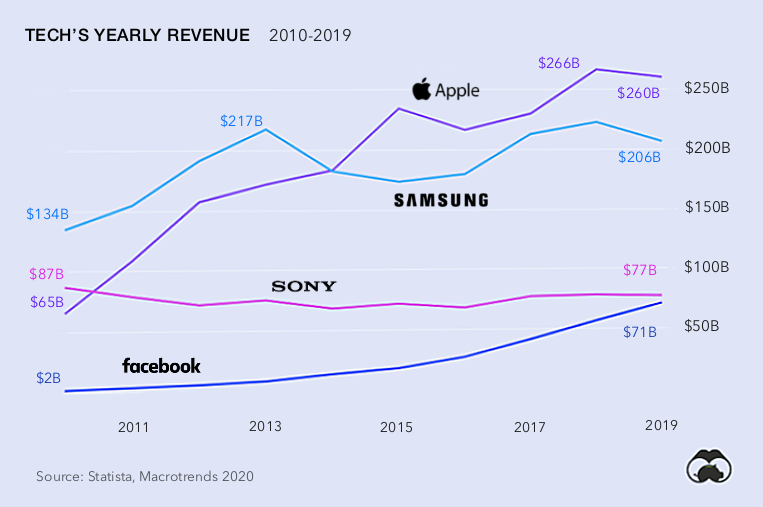

Samsung’s Evolution from Fish to Phones

Samsung spent much of the 1950s and 1960s testing market waters. The South Korean company tried everything from insurance to textiles, and most oddly, trading dehydrated fish. Following its experimental phase, Samsung released its first consumer electronic product in 1970—a black-and-white television. After making a name for itself with TVs, Samsung entered the telecommunications hardware sector in 1980 by way of acquisition. Its product diversification strategy was a successful one. Samsung went on to gain international prominence throughout the 1990s and restructured in 1993 to focus on electronics, chemicals, and engineering.

Today, Samsung is worth more than $275 billion. It has the second-largest market share of smartphone sales in North America, behind Apple.

Facebook Ratings to Friend Requests

Thanks to movies like “The Social Network”, Facebook’s origin story has been hotly discussed. “Facemash” was developed in Mark Zuckerberg’s Harvard dorm room, as a platform that compared and rated pictures of coeds. When it pivoted from rating coeds to connecting coeds, “TheFacebook” quickly took off across Harvard and spread across the university ecosystem.

In 2012, Facebook became the first social network to reach 1 billion users. It now boasts more than 2.7 billion users across the planet. In total, the company has more than 3.14 billion account holders across its platforms, which include acquired companies like WhatsApp, Instagram, and Messenger.

— Henry Ford

About Them Apples: Mac Starts with Schools

From the jump, Apple was strategic. To open up the market for personal computers, Steve Jobs (Apple’s now legendary co-founder), personally lobbied multiple levels of government to increase tax incentives for companies that donate to schools—a remarkable undertaking for a scrappy startup. After his federal lobbying fell through, Jobs was successful in the state of California. By initially focusing on education—and giving their computers away for free to the California school system—Apple amassed a potential user base and claimed mindshare. — Hacker Education Today, an Apple computer is the go-to tool of the creative class. In 2018 alone, the company sold 18.21 million Mac computers. By early 2020, there were 1.5 billion active iPhone devices, and by the end of August 2020, Apple was worth more than $2 trillion. Apple proves that even with a solid strategy and excellent products, the corporate machine can still veer out of control. Jobs was famously forced out of the company in 1985. In his absence, ventures backfired. After his return in 1997—and the subsequent introduction of the iPod—Apple went on to become one of the most lucrative tech companies in the world.

Sony Sticks to Electronics

Sony’s brand name has long been synonymous with quality—but its first electronic product didn’t make it to market. After WWII, Sony wanted to make a rice cooker to serve post-war Japan, so the company developed a simple wooden rice cooker with electrodes attached. Due to inconsistent electrical power throughout the country, the project was shelved. Sony, however, stuck to electronics. After establishing its brand name with TVs, Sony branched out into gaming and is now the largest video game console manufacturer and game publisher.

As of 2020, its global revenue neared $77 billion. The company brings in 26.7% of sales from game and network services. Meanwhile, nearly $4.5 billion in revenue stems from its mobile communications segment.

YouTube’s Dating Game

Gen Z has become the first generation to watch more YouTube than TV. But when YouTube was founded in 2005, it was a bit more akin to Tinder. Back when video dating was still a thing, YouTube aimed to take the experience online. The company even went so far as to offer women money to upload videos. However, the idea didn’t click. YouTube’s co-founders decided to release a platform that would allow for any video type—and from there, sparks flew.

YouTube was acquired by Google in 2006 for $1.7 billion. By 2019, it had more than 1.68 billion users worldwide.

— Jeff Bezos

Twitter Ditches Talk for Type

For the platform known for a deluge of words and character-count limits, it may be a surprise that Twitter was meant to be a podcasting platform called “Odeo”. When Apple announced its entry into the podcasting world, the team realized they couldn’t compete. Instead, Odeo turned to its engineering manager Jack Dorsey to pivot the company into his side project, now known as Twitter. Although original Odeo investors weren’t happy with the move, the strategy proved successful.

In 2019, Twitter raked in $3.46 billion in revenue. It averages 150 million daily users. Twitter collected advertising revenue of nearly $3 billion in 2019. It was valued at nearly $35 billion in 2020.

Rubber Boots to Phones: Nokia’s Puzzling Pivot

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, Nokia made a very different kind of product—rubber boots. The Kontio product line was successful, but in the early 1990s, the company pivoted to focus on mobile connectivity and hardware. Released in 2003 and 2005, the Nokia 1100 and 1110 still hold the record for the world’s most popular phones, with more than 250 million units sold of each. Although Android and iPhone have sped past Nokia as smartphone manufacturers, Nokia is still worth about $24 billion. While its phones were incredibly popular, the pivot took a financial toll, and the company’s mobile and services division was acquired by Microsoft in 2013.

Shopify Rides into Sales

Frustrated with the online sales experience, the founders of Snowdevil—a Canadian secondhand snowboard shop—decided to create their own online experience. Instead of their gear taking off, it was their platform that caught wind with consumers, and the team knew they were on to something. In the span of two years, 2004-2006, Snowdevil became Shopify. Less than a decade later, it went public in 2015.

Today, Shopify claims 20% of global market share among ecommerce platforms. It has more than 800,000 online sellers using the platform.

Nintendo Games Span Centuries

When it comes to gaming, Nintendo has more than 150 years of experience to draw from. Beginning with hand-painted cards in the 1800s, Nintendo sold cards for multiple games, including gambling. Their nature-inspired and cartoon-like style was carried into the 20th century when Nintendo partnered with Disney to create playing cards. Like other tech companies, Nintendo has ventured into some unusual markets over the years, including ramen noodles. However, its primary focus has remained on games. In 1985, Nintendo released what would become the world’s most popular video game, Super Mario Bros—which has sold more than 40 million copies worldwide.

The Winding Road to Success

Silicon Valley’s “fail fast” philosophy—pressure testing and pivoting—can be a lucrative, albeit grueling, one. It’s an adaptive strategy that isn’t relegated to tech companies alone. Pivots large and small are often a key part of any company’s evolution, from products and services to marketing strategies. Beyond bizarre beginnings and pivots, if there’s one thing successful companies have in common, it’s the audacity to evolve. on But fast forward to the end of last week, and SVB was shuttered by regulators after a panic-induced bank run. So, how exactly did this happen? We dig in below.

Road to a Bank Run

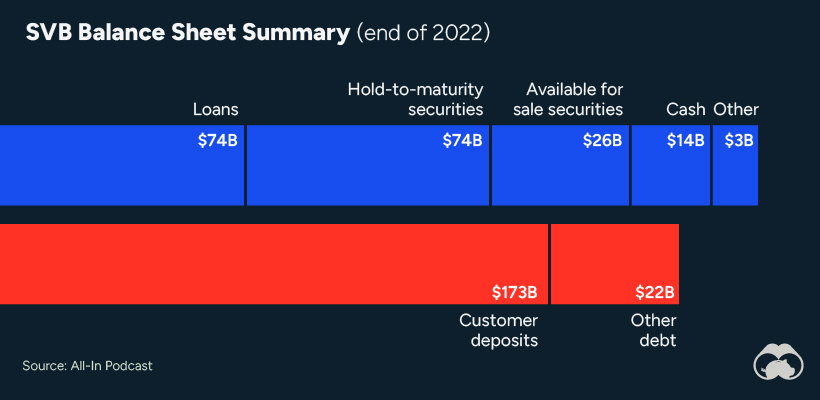

SVB and its customers generally thrived during the low interest rate era, but as rates rose, SVB found itself more exposed to risk than a typical bank. Even so, at the end of 2022, the bank’s balance sheet showed no cause for alarm.

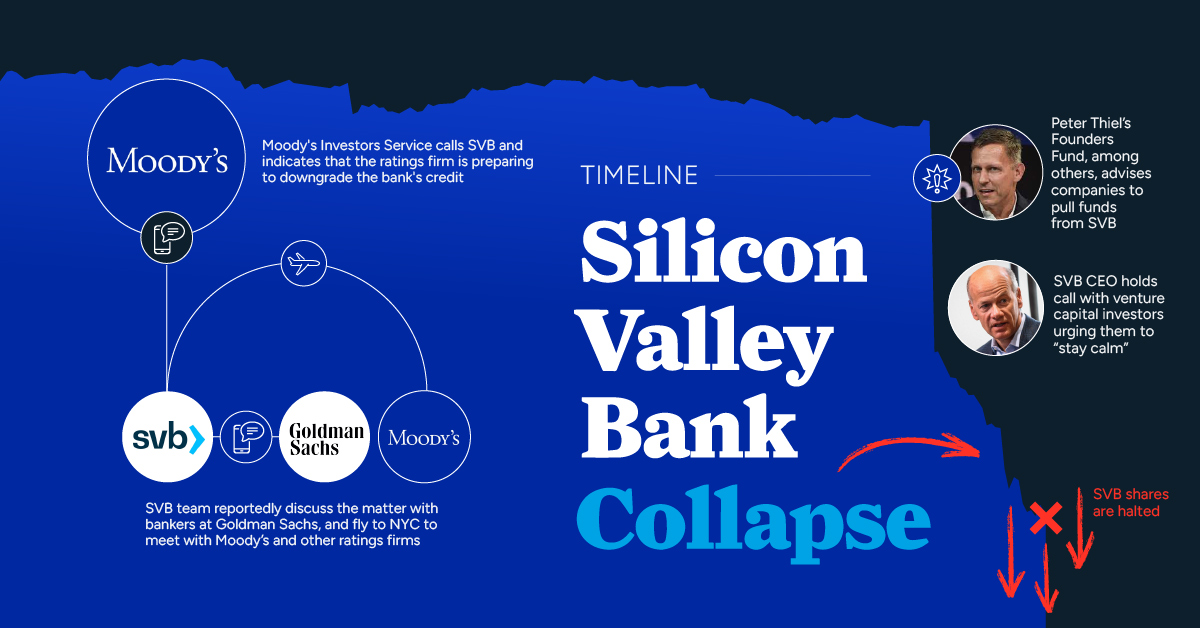

As well, the bank was viewed positively in a number of places. Most Wall Street analyst ratings were overwhelmingly positive on the bank’s stock, and Forbes had just added the bank to its Financial All-Stars list. Outward signs of trouble emerged on Wednesday, March 8th, when SVB surprised investors with news that the bank needed to raise more than $2 billion to shore up its balance sheet. The reaction from prominent venture capitalists was not positive, with Coatue Management, Union Square Ventures, and Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund moving to limit exposure to the 40-year-old bank. The influence of these firms is believed to have added fuel to the fire, and a bank run ensued. Also influencing decision making was the fact that SVB had the highest percentage of uninsured domestic deposits of all big banks. These totaled nearly $152 billion, or about 97% of all deposits. By the end of the day, customers had tried to withdraw $42 billion in deposits.

What Triggered the SVB Collapse?

While the collapse of SVB took place over the course of 44 hours, its roots trace back to the early pandemic years. In 2021, U.S. venture capital-backed companies raised a record $330 billion—double the amount seen in 2020. At the time, interest rates were at rock-bottom levels to help buoy the economy. Matt Levine sums up the situation well: “When interest rates are low everywhere, a dollar in 20 years is about as good as a dollar today, so a startup whose business model is “we will lose money for a decade building artificial intelligence, and then rake in lots of money in the far future” sounds pretty good. When interest rates are higher, a dollar today is better than a dollar tomorrow, so investors want cash flows. When interest rates were low for a long time, and suddenly become high, all the money that was rushing to your customers is suddenly cut off.” Source: Pitchbook Why is this important? During this time, SVB received billions of dollars from these venture-backed clients. In one year alone, their deposits increased 100%. They took these funds and invested them in longer-term bonds. As a result, this created a dangerous trap as the company expected rates would remain low. During this time, SVB invested in bonds at the top of the market. As interest rates rose higher and bond prices declined, SVB started taking major losses on their long-term bond holdings.

Losses Fueling a Liquidity Crunch

When SVB reported its fourth quarter results in early 2023, Moody’s Investor Service, a credit rating agency took notice. In early March, it said that SVB was at high risk for a downgrade due to its significant unrealized losses. In response, SVB looked to sell $2 billion of its investments at a loss to help boost liquidity for its struggling balance sheet. Soon, more hedge funds and venture investors realized SVB could be on thin ice. Depositors withdrew funds in droves, spurring a liquidity squeeze and prompting California regulators and the FDIC to step in and shut down the bank.

What Happens Now?

While much of SVB’s activity was focused on the tech sector, the bank’s shocking collapse has rattled a financial sector that is already on edge.

The four biggest U.S. banks lost a combined $52 billion the day before the SVB collapse. On Friday, other banking stocks saw double-digit drops, including Signature Bank (-23%), First Republic (-15%), and Silvergate Capital (-11%).

Source: Morningstar Direct. *Represents March 9 data, trading halted on March 10.

When the dust settles, it’s hard to predict the ripple effects that will emerge from this dramatic event. For investors, the Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen announced confidence in the banking system remaining resilient, noting that regulators have the proper tools in response to the issue.

But others have seen trouble brewing as far back as 2020 (or earlier) when commercial banking assets were skyrocketing and banks were buying bonds when rates were low.