As a company like Tesla has discovered over its relatively short history, the manufacturing processes required to make thousands of cars at scale are extremely costly and ridden with unexpected setbacks. To make matters worse the vehicle market is ultra competitive, with very little room for error. Unless you have a game-changing innovation, powerful brand loyalty, or strong cost leadership, it’s easy to have your lunch eaten by competitors – or to get gobbled up in the industry’s next M&A transaction.

The Auto Landscape

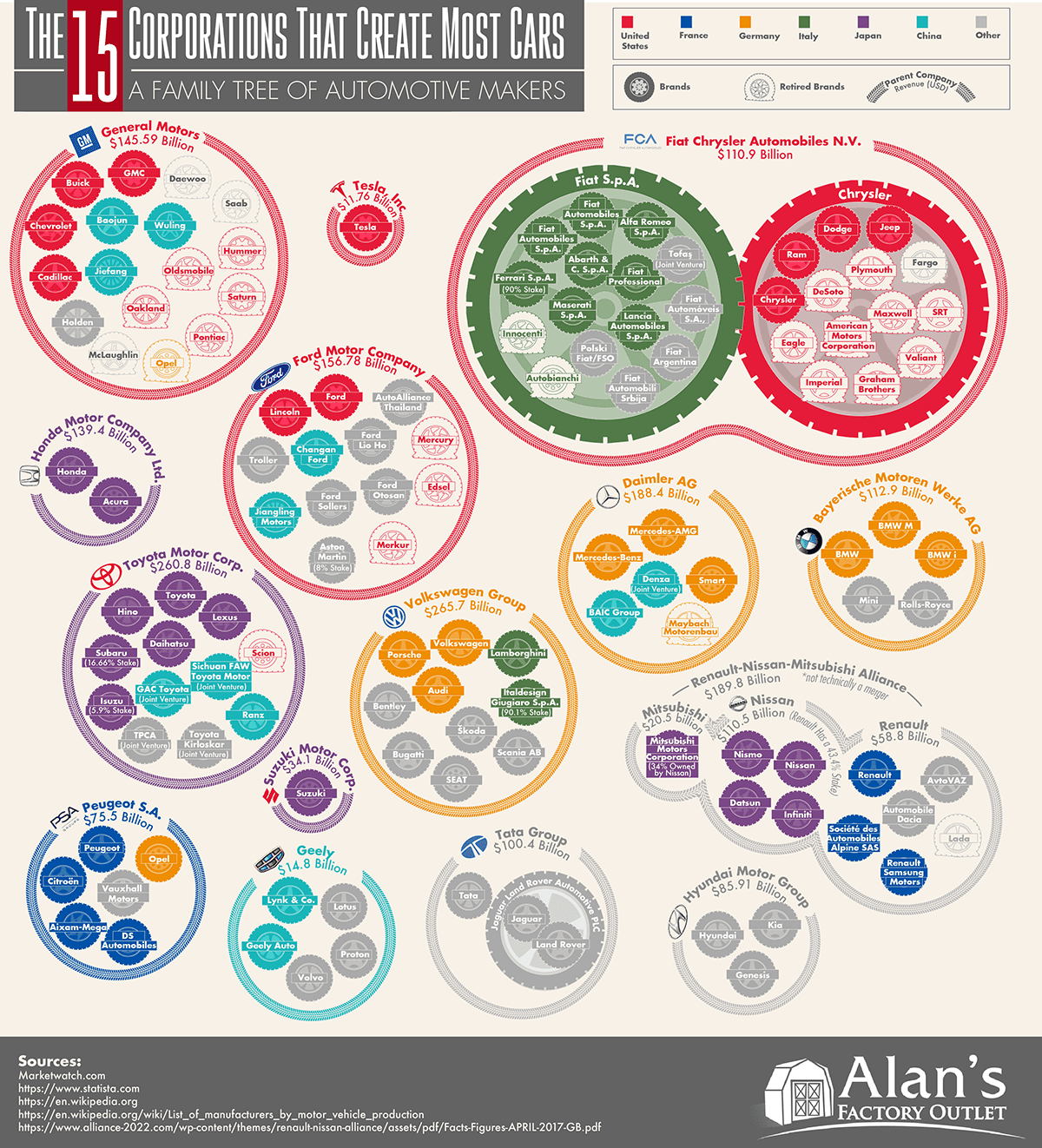

Today’s infographic comes to us from Alan’s Factory Outlet, and it shows the 15 corporations that make the majority of the world’s cars. Here are those corporations, sorted by annual revenue in U.S. dollars:

A select few of these companies, such as Tesla or Suzuki, make only one brand of car. As seen in the graphic, however, the majority of these corporations are actually conglomerates with multiple brands falling under one parent company. These brands are either created strategically by the parent company to target new markets, or they are the result of mergers and acquisitions.

Corporate Family Trees

Here are how these additional brands get added or adopted into each corporate family tree:

- Filling a Strategic Need In the 1960s and 1970s, Japanese autos started flooding the North American market – and by 1975, Toyota was the top imported brand in the United States. While Japanese automakers like Toyota, Honda, and Nissan were able to capture market share, at this time they still did not have the reputation they had today. That’s why, almost simultaneously, these same major Japanese automakers launched separate luxury brands to tap into new market segments. In a short span, Acura (1986), Infiniti (1989) and Lexus (1989) were all founded to gain a foothold in the growing luxury market, with large amounts of success.

- Changing Hands Rather than start a brand from scratch, big automakers can also dip into their financial resources to acquire a brand that suits their strategic needs. A good example of this is India’s Tata Motors, a company that was expanding rather aggressively in the 2000s. Tata Motors purchased the Jaguar Land Rover subsidiary from Ford in 2008, and now owns these well-known British luxury brands.

- A Good Old-Fashioned Merger In the last 20 years, Chrysler has been a part of two massive mergers. The first one with Germany’s Daimler Benz happened in 1998, and fell apart because of cultural differences between the companies. The second merger was a little more one-sided: in 2009, Italian company Fiat moved in to take control of Chrysler after the latter’s bankruptcy. The union is still together today.

- Staying Alive After Kia Motors filed for bankruptcy in 1997 during the Asian financial crisis, a fellow South Korean automaker came to the rescue. Hyundai outbid Ford to grab a 51% stake in the company – and while that stake is less now for various reasons, the two brands are still tied at the hip today. on These are in the form of Treasury securities, some of the most liquid assets worldwide. Central banks use them for foreign exchange reserves and private investors flock to them during flights to safety thanks to their perceived low default risk. Beyond these reasons, foreign investors may buy Treasuries as a store of value. They are often used as collateral during certain international trade transactions, or countries can use them to help manage exchange rate policy. For example, countries may buy Treasuries to protect their currency’s exchange rate from speculation. In the above graphic, we show the foreign holders of the U.S. national debt using data from the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

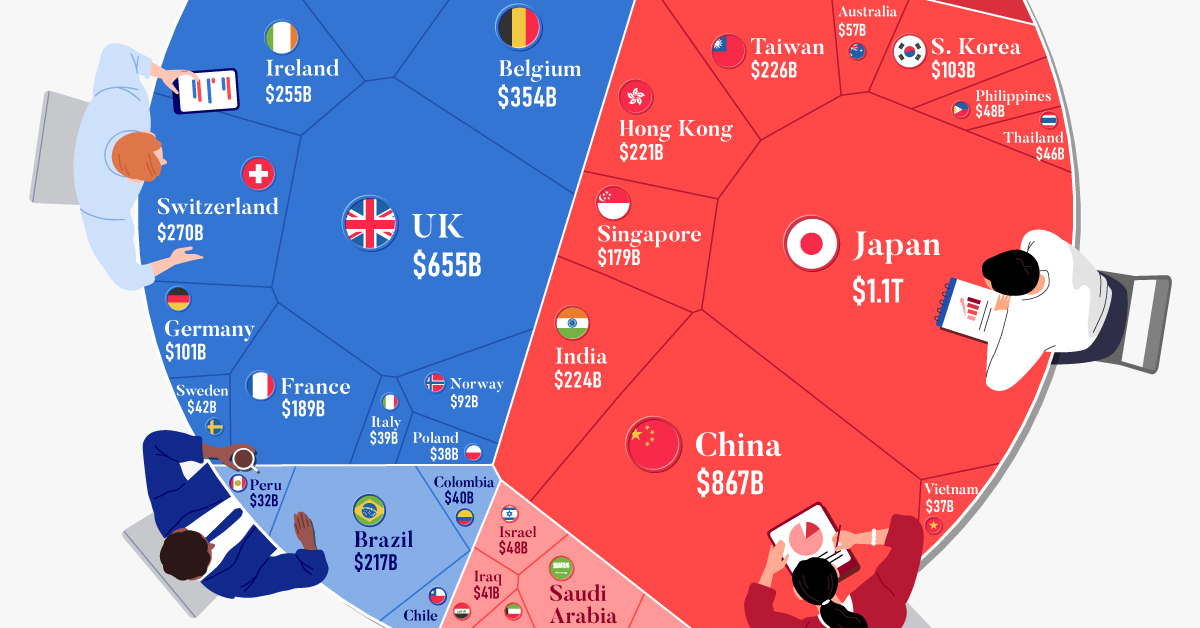

Top Foreign Holders of U.S. Debt

With $1.1 trillion in Treasury holdings, Japan is the largest foreign holder of U.S. debt. Japan surpassed China as the top holder in 2019 as China shed over $250 billion, or 30% of its holdings in four years. This bond offloading by China is the one way the country can manage the yuan’s exchange rate. This is because if it sells dollars, it can buy the yuan when the currency falls. At the same time, China doesn’t solely use the dollar to manage its currency—it now uses a basket of currencies. Here are the countries that hold the most U.S. debt: As the above table shows, the United Kingdom is the third highest holder, at over $655 billion in Treasuries. Across Europe, 13 countries are notable holders of these securities, the highest in any region, followed by Asia-Pacific at 11 different holders. A handful of small nations own a surprising amount of U.S. debt. With a population of 70,000, the Cayman Islands own a towering amount of Treasury bonds to the tune of $284 billion. There are more hedge funds domiciled in the Cayman Islands per capita than any other nation worldwide. In fact, the four smallest nations in the visualization above—Cayman Islands, Bermuda, Bahamas, and Luxembourg—have a combined population of just 1.2 million people, but own a staggering $741 billion in Treasuries.

Interest Rates and Treasury Market Dynamics

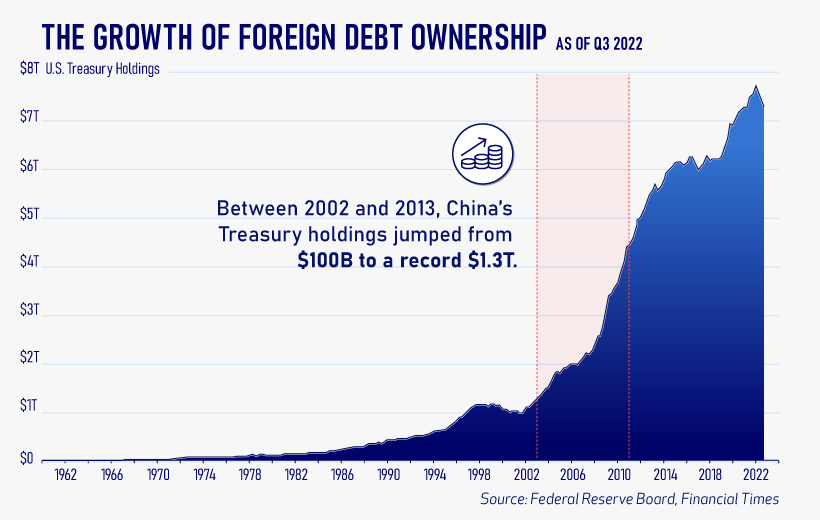

Over 2022, foreign demand for Treasuries sank 6% as higher interest rates and a strong U.S. dollar made owning these bonds less profitable. This is because rising interest rates on U.S. debt makes the present value of their future income payments lower. Meanwhile, their prices also fall. As the chart below shows, this drop in demand is a sharp reversal from 2018-2020, when demand jumped as interest rates hovered at historic lows. A similar trend took place in the decade after the 2008-09 financial crisis when U.S. debt holdings effectively tripled from $2 to $6 trillion.

Driving this trend was China’s rapid purchase of Treasuries, which ballooned from $100 billion in 2002 to a peak of $1.3 trillion in 2013. As the country’s exports and output expanded, it sold yuan and bought dollars to help alleviate exchange rate pressure on its currency. Fast-forward to today, and global interest-rate uncertainty—which in turn can impact national currency valuations and therefore demand for Treasuries—continues to be a factor impacting the future direction of foreign U.S. debt holdings.