The Global War on Cash

The Money Project is an ongoing collaboration between Visual Capitalist and Texas Precious Metals that seeks to use intuitive visualizations to explore the origins, nature, and use of money. There is a global push by lawmakers to eliminate the use of physical cash around the world. This movement is often referred to as “The War on Cash”, and there are three major players involved:

- The Initiators Who? Governments, central banks. Why? The elimination of cash will make it easier to track all types of transactions – including those made by criminals.

- The Enemy Who? Criminals, terrorists Why? Large denominations of bank notes make illegal transactions easier to perform, and increase anonymity.

- The Crossfire Who? Citizens Why? The coercive elimination of physical cash will have potential repercussions on the economy and social liberties.

Is Cash Still King?

Cash has always been king – but starting in the late 1990s, the convenience of new technologies have helped make non-cash transactions to become more viable:

Online banking Smartphones Payment technologies Encryption

By 2015, there were 426 billion cashless transactions worldwide – a 50% increase from five years before. And today, there are multiple ways to pay digitally, including:

Online banking (Visa, Mastercard, Interac) Smartphones (Apple Pay) Intermediaries ( Paypal , Square) Cryptocurrencies (Bitcoin)

The First Shots Fired

The success of these new technologies have prompted lawmakers to posit that all transactions should now be digital. Here is their case for a cashless society: Removing high denominations of bills from circulation makes it harder for terrorists, drug dealers, money launderers, and tax evaders.

$1 million in $100 bills weighs only one kilogram (2.2 lbs). Criminals move $2 trillion per year around the world each year. The U.S. $100 bill is the most popular note in the world, with 10 billion of them in circulation.

This also gives regulators more control over the economy.

More traceable money means higher tax revenues. It means there is a third-party for all transactions. Central banks can dictate interest rates that encourage (or discourage) spending to try to manage inflation. This includes ZIRP or NIRP policies.

Cashless transactions are faster and more efficient.

Banks would incur less costs by not having to handle cash. It also makes compliance and reporting easier. The “burden” of cash can be up to 1.5% of GDP, according to some experts.

But for this to be possible, they say that cash – especially large denomination bills – must be eliminated. After all, cash is still used for about 85% of all transactions worldwide.

A Declaration of War

Governments and central banks have moved swiftly in dozens of countries to start eliminating cash. Some key examples of this? Australia, Singapore, Venezuela, the U.S., and the European Central Bank have all eliminated (or have proposed to eliminate) high denomination notes. Other countries like France, Sweden and Greece have targeted adding restrictions on the size of cash transactions, reducing the amount of ATMs in the countryside, or limiting the amount of cash that can be held outside of the banking system. Finally, some countries have taken things a full step further – South Korea aims to eliminate paper currency in its entirety by 2020. But right now, the “War on Cash” can’t be mentioned without invoking images of day-long lineups in India. In November 2016, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi demonetized 500 and 1000 rupee notes, eliminating 86% of the country’s notes overnight. While Indians could theoretically exchange 500 and 1,000 rupee notes for higher denominations, it was only up to a limit of 4,000 rupees per person. Sums above that had to be routed through a bank account in a country where only 50% of Indians have such access. The Hindu has reported that there have now been 112 reported deaths associated with the Indian demonetization. Some people have committed suicide, but most deaths come from elderly people waiting in bank queues for hours or days to exchange money.

Caught in the Crossfire

The shots fired by governments to fight its war on cash may have several unintended casualties:

- Privacy

Cashless transactions would always include some intermediary or third-party. Increased government access to personal transactions and records. Certain types of transactions (gambling, etc.) could be barred or frozen by governments. Decentralized cryptocurrency could be an alternative for such transactions

- Savings

Savers could no longer have the individual freedom to store wealth “outside” of the system. Eliminating cash makes negative interest rates (NIRP) a feasible option for policymakers. A cashless society also means all savers would be “on the hook” for bank bail-in scenarios. Savers would have limited abilities to react to extreme monetary events like deflation or inflation.

- Human Rights

Rapid demonetization has violated people’s rights to life and food. In India, removing the 500 and 1,000 rupee notes has caused multiple human tragedies, including patients being denied treatment and people not being able to afford food. Demonetization also hurts people and small businesses that make their livelihoods in the informal sectors of the economy.

- Cybersecurity

With all wealth stored digitally, the potential risk and impact of cybercrime increases. Hacking or identity theft could destroy people’s entire life savings. The cost of online data breaches is already expected to reach $2.1 trillion by 2019, according to Juniper Research.

As the War on Cash accelerates, many shots will be fired. The question is: who will take the majority of the damage?

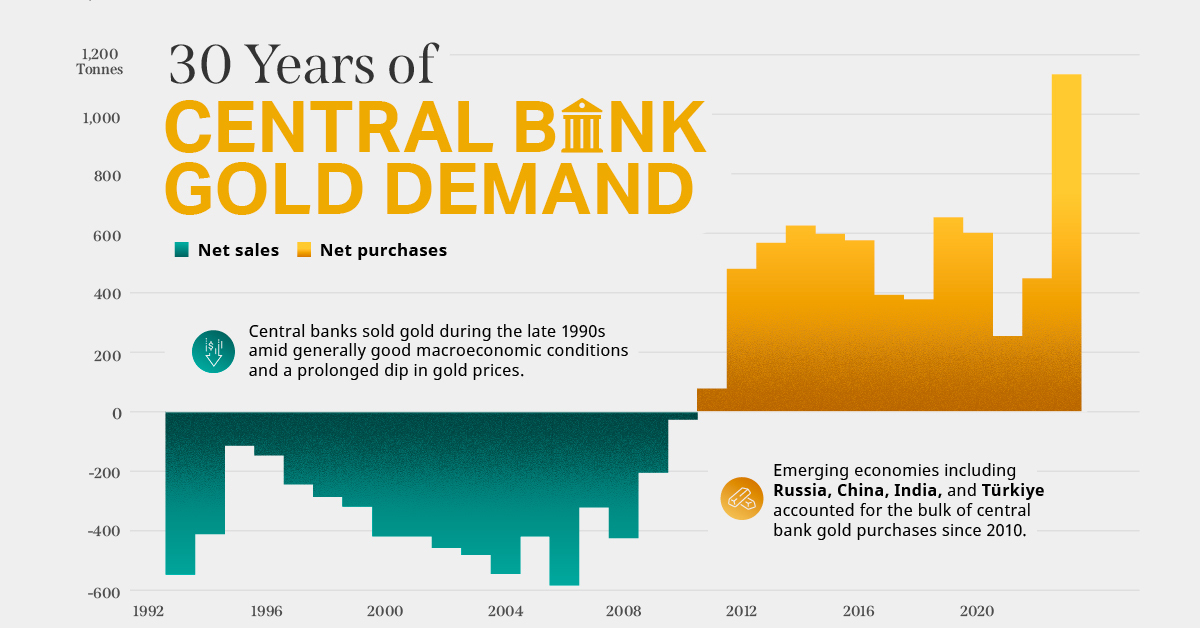

on Did you know that nearly one-fifth of all the gold ever mined is held by central banks? Besides investors and jewelry consumers, central banks are a major source of gold demand. In fact, in 2022, central banks snapped up gold at the fastest pace since 1967. However, the record gold purchases of 2022 are in stark contrast to the 1990s and early 2000s, when central banks were net sellers of gold. The above infographic uses data from the World Gold Council to show 30 years of central bank gold demand, highlighting how official attitudes toward gold have changed in the last 30 years.

Why Do Central Banks Buy Gold?

Gold plays an important role in the financial reserves of numerous nations. Here are three of the reasons why central banks hold gold:

Balancing foreign exchange reserves Central banks have long held gold as part of their reserves to manage risk from currency holdings and to promote stability during economic turmoil. Hedging against fiat currencies Gold offers a hedge against the eroding purchasing power of currencies (mainly the U.S. dollar) due to inflation. Diversifying portfolios Gold has an inverse correlation with the U.S. dollar. When the dollar falls in value, gold prices tend to rise, protecting central banks from volatility. The Switch from Selling to Buying In the 1990s and early 2000s, central banks were net sellers of gold. There were several reasons behind the selling, including good macroeconomic conditions and a downward trend in gold prices. Due to strong economic growth, gold’s safe-haven properties were less valuable, and low returns made it unattractive as an investment. Central bank attitudes toward gold started changing following the 1997 Asian financial crisis and then later, the 2007–08 financial crisis. Since 2010, central banks have been net buyers of gold on an annual basis. Here’s a look at the 10 largest official buyers of gold from the end of 1999 to end of 2021: Rank CountryAmount of Gold Bought (tonnes)% of All Buying #1🇷🇺 Russia 1,88828% #2🇨🇳 China 1,55223% #3🇹🇷 Türkiye 5418% #4🇮🇳 India 3956% #5🇰🇿 Kazakhstan 3455% #6🇺🇿 Uzbekistan 3115% #7🇸🇦 Saudi Arabia 1803% #8🇹🇭 Thailand 1682% #9🇵🇱 Poland1282% #10🇲🇽 Mexico 1152% Total5,62384% Source: IMF The top 10 official buyers of gold between end-1999 and end-2021 represent 84% of all the gold bought by central banks during this period. Russia and China—arguably the United States’ top geopolitical rivals—have been the largest gold buyers over the last two decades. Russia, in particular, accelerated its gold purchases after being hit by Western sanctions following its annexation of Crimea in 2014. Interestingly, the majority of nations on the above list are emerging economies. These countries have likely been stockpiling gold to hedge against financial and geopolitical risks affecting currencies, primarily the U.S. dollar. Meanwhile, European nations including Switzerland, France, Netherlands, and the UK were the largest sellers of gold between 1999 and 2021, under the Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) framework. Which Central Banks Bought Gold in 2022? In 2022, central banks bought a record 1,136 tonnes of gold, worth around $70 billion. Country2022 Gold Purchases (tonnes)% of Total 🇹🇷 Türkiye14813% 🇨🇳 China 625% 🇪🇬 Egypt 474% 🇶🇦 Qatar333% 🇮🇶 Iraq 343% 🇮🇳 India 333% 🇦🇪 UAE 252% 🇰🇬 Kyrgyzstan 61% 🇹🇯 Tajikistan 40.4% 🇪🇨 Ecuador 30.3% 🌍 Unreported 74165% Total1,136100% Türkiye, experiencing 86% year-over-year inflation as of October 2022, was the largest buyer, adding 148 tonnes to its reserves. China continued its gold-buying spree with 62 tonnes added in the months of November and December, amid rising geopolitical tensions with the United States. Overall, emerging markets continued the trend that started in the 2000s, accounting for the bulk of gold purchases. Meanwhile, a significant two-thirds, or 741 tonnes of official gold purchases were unreported in 2022. According to analysts, unreported gold purchases are likely to have come from countries like China and Russia, who are looking to de-dollarize global trade to circumvent Western sanctions.

There were several reasons behind the selling, including good macroeconomic conditions and a downward trend in gold prices. Due to strong economic growth, gold’s safe-haven properties were less valuable, and low returns made it unattractive as an investment.

Central bank attitudes toward gold started changing following the 1997 Asian financial crisis and then later, the 2007–08 financial crisis. Since 2010, central banks have been net buyers of gold on an annual basis.

Here’s a look at the 10 largest official buyers of gold from the end of 1999 to end of 2021:

Source: IMF

The top 10 official buyers of gold between end-1999 and end-2021 represent 84% of all the gold bought by central banks during this period.

Russia and China—arguably the United States’ top geopolitical rivals—have been the largest gold buyers over the last two decades. Russia, in particular, accelerated its gold purchases after being hit by Western sanctions following its annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Interestingly, the majority of nations on the above list are emerging economies. These countries have likely been stockpiling gold to hedge against financial and geopolitical risks affecting currencies, primarily the U.S. dollar.

Meanwhile, European nations including Switzerland, France, Netherlands, and the UK were the largest sellers of gold between 1999 and 2021, under the Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) framework.

Which Central Banks Bought Gold in 2022?

In 2022, central banks bought a record 1,136 tonnes of gold, worth around $70 billion. Türkiye, experiencing 86% year-over-year inflation as of October 2022, was the largest buyer, adding 148 tonnes to its reserves. China continued its gold-buying spree with 62 tonnes added in the months of November and December, amid rising geopolitical tensions with the United States. Overall, emerging markets continued the trend that started in the 2000s, accounting for the bulk of gold purchases. Meanwhile, a significant two-thirds, or 741 tonnes of official gold purchases were unreported in 2022. According to analysts, unreported gold purchases are likely to have come from countries like China and Russia, who are looking to de-dollarize global trade to circumvent Western sanctions.