Tapping into the properties of the digital world allows these companies to do more with less. They can have global reach with minimal infrastructure, massive scale with little overhead, and impressive revenues without any physical inventory. Tech companies can even “provide” a service by simply connecting people through a platform, rather than knowing how to perform the service itself.

“Our Greatest Asset”

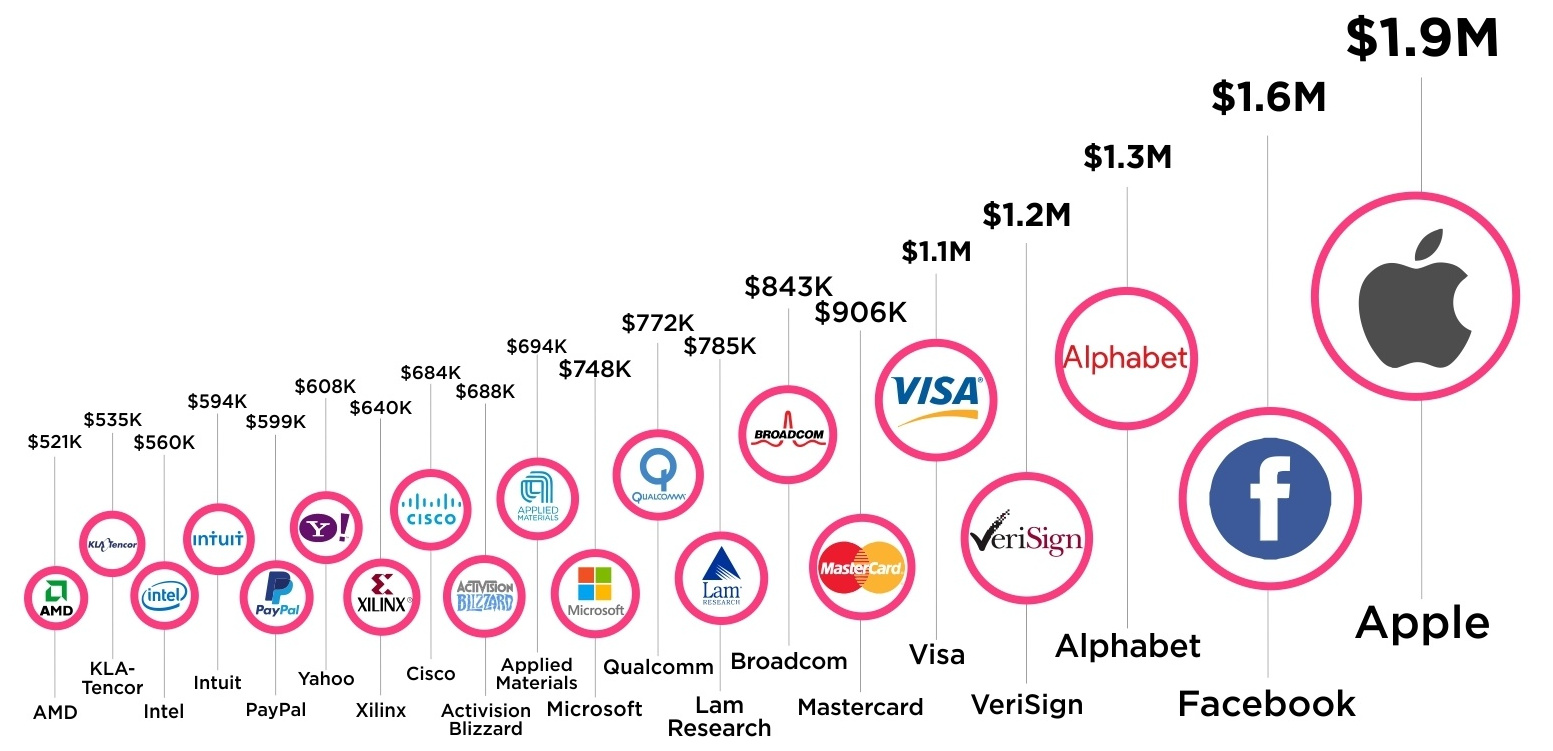

With this kind of scale, every action taken by an employee packs an extra punch to have an effect on company performance. It’s why companies like Google, Facebook, and Microsoft are willing to pay an arm and a leg for the smartest engineers. These teams are not physically turning out widgets in a factory under the constraints of normal economic factors – instead, they are applying their brains to a codebase, and even the tiniest cost savings can add up when multiplied by millions of users. Today’s visualization from cost information site HowMuch.net helps put this all in perspective by showing revenue per employee of some of the world’s largest tech companies that are a part of the S&P 500. Here’s the data in table form:

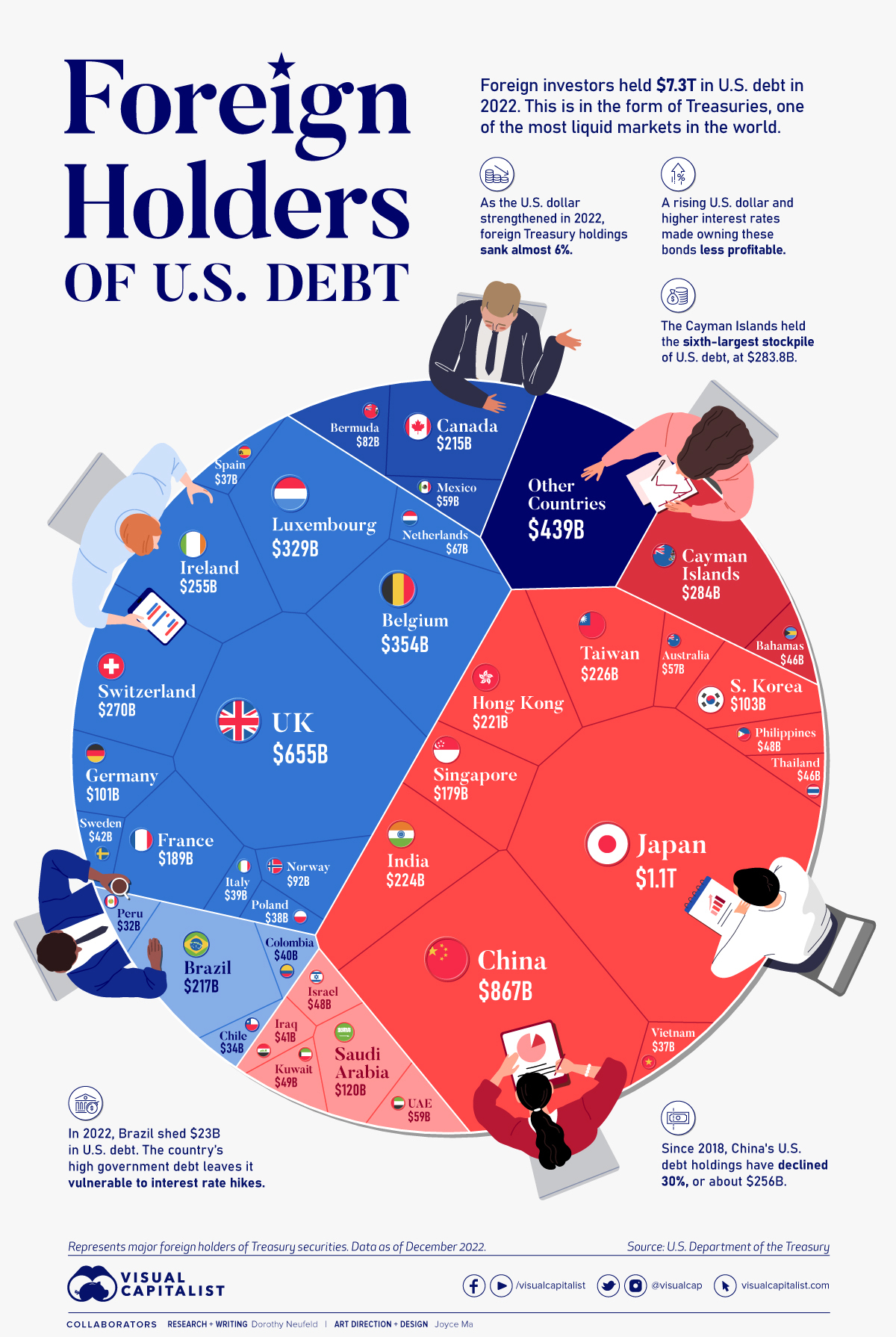

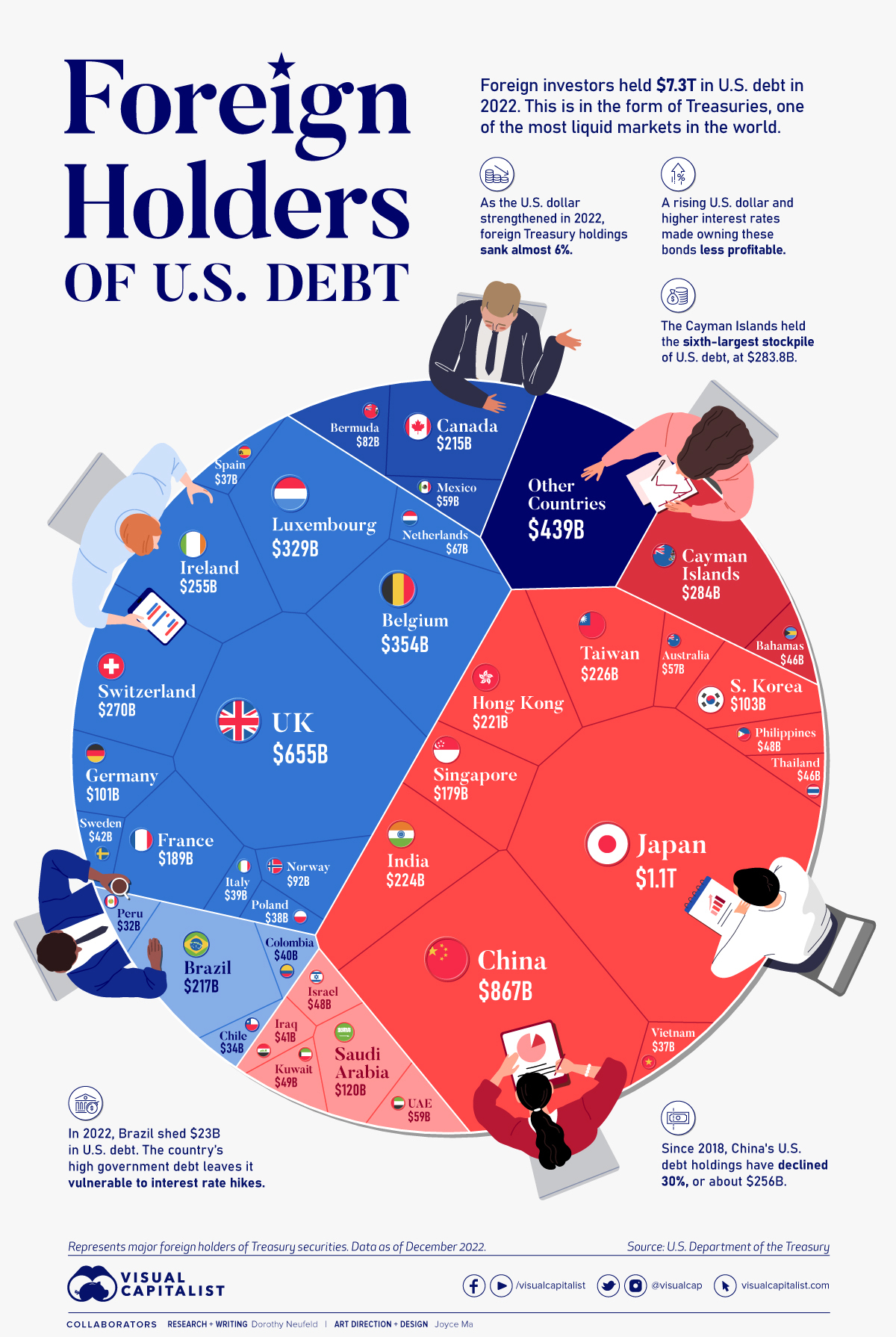

Facebook, Alphabet, and Visa each bring in over $1 million in revenue per employee – and Apple rakes in nearly $2 million per person. While these numbers are impressive, not all tech companies on the S&P 500 are masters of scale. In fact, the average tech company brings in closer to $480,000 of revenue per employee. This amount is comparable to other sectors that make up the S&P 500, like Materials ($600,000 per employee) or Consumer Discretionary ($420,000 per employee). on These are in the form of Treasury securities, some of the most liquid assets worldwide. Central banks use them for foreign exchange reserves and private investors flock to them during flights to safety thanks to their perceived low default risk. Beyond these reasons, foreign investors may buy Treasuries as a store of value. They are often used as collateral during certain international trade transactions, or countries can use them to help manage exchange rate policy. For example, countries may buy Treasuries to protect their currency’s exchange rate from speculation. In the above graphic, we show the foreign holders of the U.S. national debt using data from the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

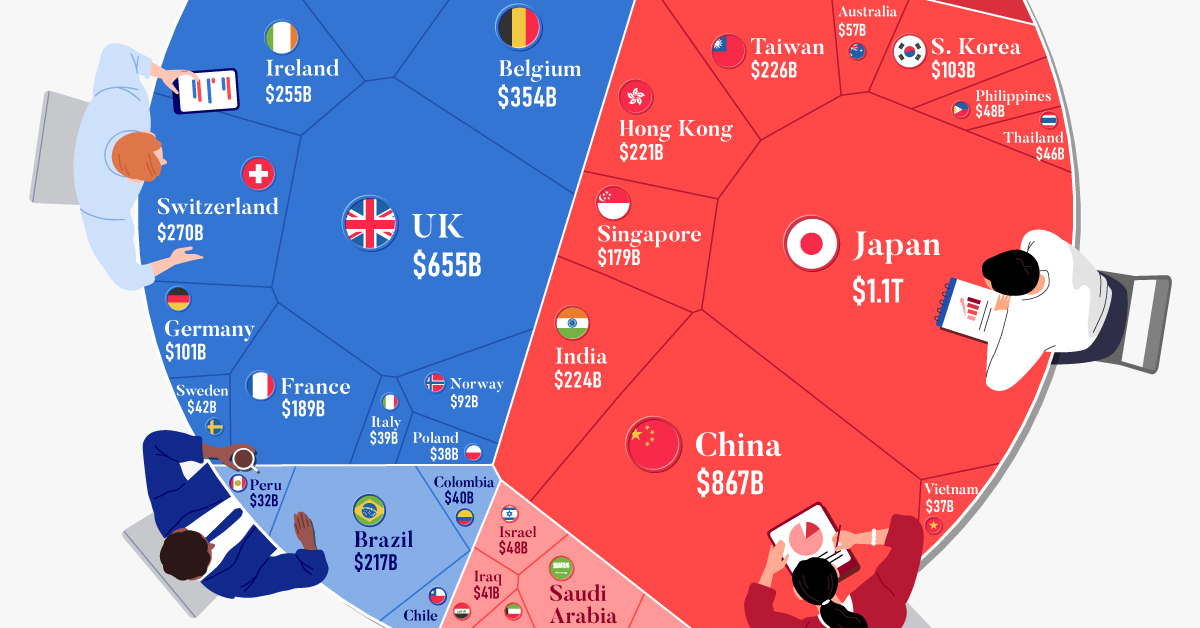

Top Foreign Holders of U.S. Debt

With $1.1 trillion in Treasury holdings, Japan is the largest foreign holder of U.S. debt. Japan surpassed China as the top holder in 2019 as China shed over $250 billion, or 30% of its holdings in four years. This bond offloading by China is the one way the country can manage the yuan’s exchange rate. This is because if it sells dollars, it can buy the yuan when the currency falls. At the same time, China doesn’t solely use the dollar to manage its currency—it now uses a basket of currencies. Here are the countries that hold the most U.S. debt: As the above table shows, the United Kingdom is the third highest holder, at over $655 billion in Treasuries. Across Europe, 13 countries are notable holders of these securities, the highest in any region, followed by Asia-Pacific at 11 different holders. A handful of small nations own a surprising amount of U.S. debt. With a population of 70,000, the Cayman Islands own a towering amount of Treasury bonds to the tune of $284 billion. There are more hedge funds domiciled in the Cayman Islands per capita than any other nation worldwide. In fact, the four smallest nations in the visualization above—Cayman Islands, Bermuda, Bahamas, and Luxembourg—have a combined population of just 1.2 million people, but own a staggering $741 billion in Treasuries.

Interest Rates and Treasury Market Dynamics

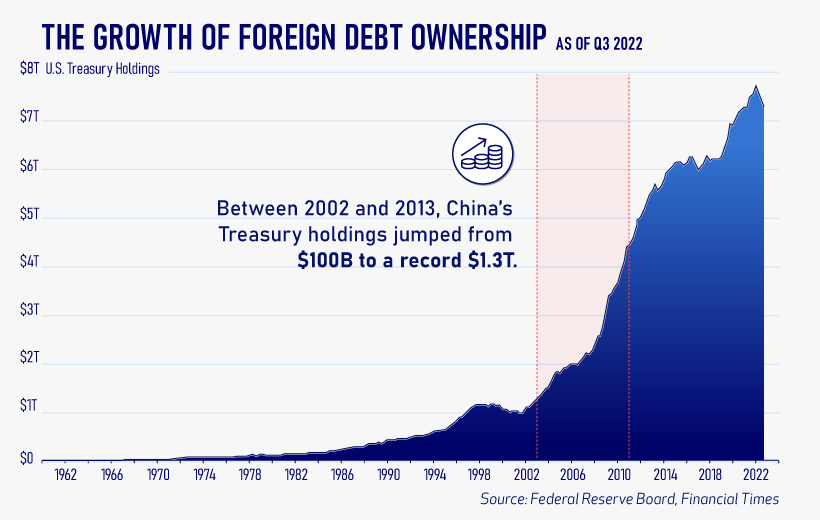

Over 2022, foreign demand for Treasuries sank 6% as higher interest rates and a strong U.S. dollar made owning these bonds less profitable. This is because rising interest rates on U.S. debt makes the present value of their future income payments lower. Meanwhile, their prices also fall. As the chart below shows, this drop in demand is a sharp reversal from 2018-2020, when demand jumped as interest rates hovered at historic lows. A similar trend took place in the decade after the 2008-09 financial crisis when U.S. debt holdings effectively tripled from $2 to $6 trillion.

Driving this trend was China’s rapid purchase of Treasuries, which ballooned from $100 billion in 2002 to a peak of $1.3 trillion in 2013. As the country’s exports and output expanded, it sold yuan and bought dollars to help alleviate exchange rate pressure on its currency. Fast-forward to today, and global interest-rate uncertainty—which in turn can impact national currency valuations and therefore demand for Treasuries—continues to be a factor impacting the future direction of foreign U.S. debt holdings.