But this map allows us to step back and look at the region in its larger context. While most media has focused on the tensions, this map breaks down the entire Caucasus region, providing key facts and information. What are the countries that comprise the region? What is the main economic activity in the area? How is the population distributed? Let’s begin.

The Basics

The Caucasus region is characterized by far-reaching mountain ranges, that have long separated people and created distinct ethnic, linguistic, and religious identities over thousands of years. Today, the region spans over three main countries: Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, and is bordered by Russia, Turkey, and Iran. Focusing on the main three, here’s a look at some basic demographics:

🇦🇿 Azerbaijan Population: 10.4 million 🇦🇲 Armenia Population: 3.0 million 🇬🇪 Georgia Population: 4.1 million

Home to around 20 million, the Caucasus region touches the Caspian Sea to the East and the Black Sea to the West. It is an area distinctly situated between Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, but is defined by most categorizations as Central Asian.

🇦🇿 Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan is the biggest country in the region, both in terms of land mass and population. The Nagorno-Karabakh region is located within the official borders of Azerbaijan, and is inhabited almost entirely by ethnic Armenians. The majority of Azeris are Muslim, however, the country is considered one of the most secular Muslim countries in the world. Azerbaijani or Azeri is the most widely spoken language with more than 92% of people speaking it. Just over 1% in the country speak Russian as a first language and another 1% speak Armenian as a primary language. Perhaps, unsurprisingly, a similar percentage share defines the amount of ethnic Russians and Armenians in Azerbaijan, at 1.5% and 1.3% respectively.

🇦🇲 Armenia

Like both its neighbors, Armenia gained independence at the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Unlike its neighbors, however, it is entirely landlocked. The country is a majority Christian nation, with an ethnic makeup of nearly 98% Armenians and the most widely spoken language being Armenian, according to the government. The population count has fallen since the collapse of the USSR, and has been relatively flat in more recent years.

🇬🇪 Georgia

Georgia is slightly smaller than Azerbaijan in size; the country shares a long border with Russia to its north and features a long coastline on the Black Sea. Georgia’s population growth shares a similar story to many other former Soviet republics. While total population has decreased slightly over recent years, the growth in ethnic nationals (Georgians) has actually increased. The country is majority Christian and Georgian is the most popular language.

Where do People Live Across the Caucasus Region?

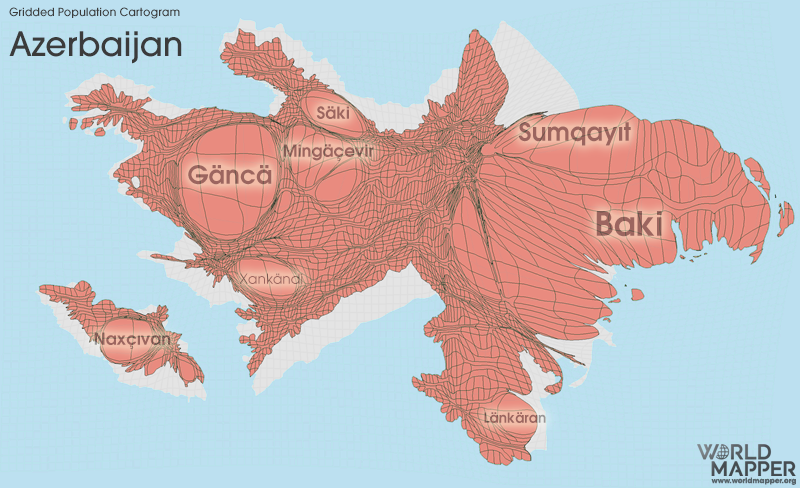

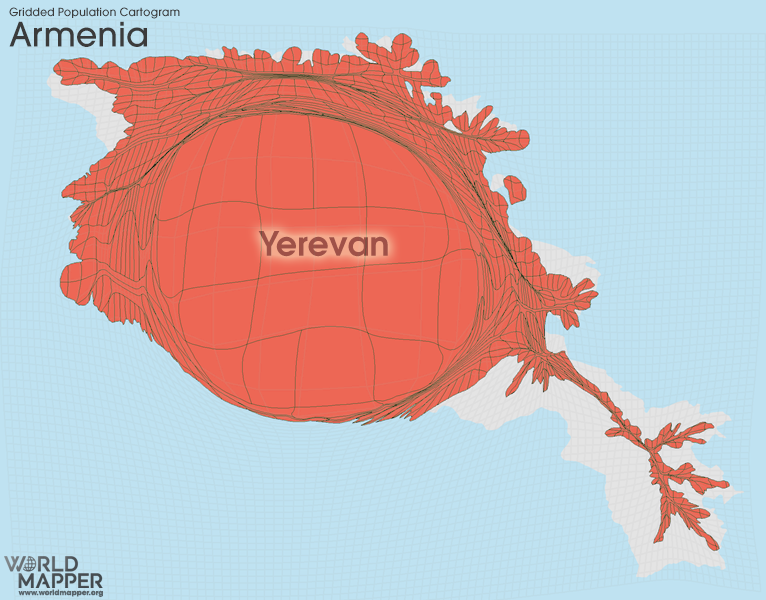

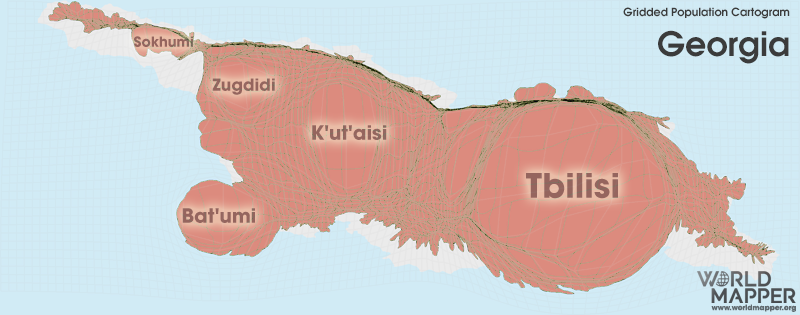

So how are these populations concentrated throughout the region? These cartograms from World Mapper, break it down by country:

Azerbaijan

Most people live in and around the capital Baku, a port city on the Caspian Sea. However, a number of people also live inland closer to the Armenian and Georgian borders.

Armenia

In Armenia the population heavily skews towards its capital city of Yerevan, which has a population of 1.1 million.

Georgia

Georgia’s population distribution is slightly more even than its neighbors with a preference towards the capital Tbilisi.

The Economy of the Caucasus Region

Now let’s dive into the economic activity in the Caucasus. In some parts, the region is oil-rich with access to resources like the vast oil fields in the Caspian Sea off Azerbaijan’s coast. In fact, the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Pipeline carries nearly 1 million barrels of oil from the oilfields to Turkey every day. Stepping back, here’s a glance at regional GDPs:

🇦🇿 Azerbaijan GDP: $42.6 billion 🇬🇪 Georgia: $15.9 billion 🇦🇲 Armenia GDP: $12.7 billion

Azerbaijan is the Caucasus region’s biggest economy. It is the most economically developed country of the three, having seen rapid GDP growth since its transition from a Soviet republic. At its height in the early 2000s, the national GDP was growing at yearly rates of 25%-35%. Today, its oil and gas exports are proving extremely lucrative given the European energy crisis due to the war in Ukraine. Fossil fuels make up about 95% of the country’s export revenue. Both Armenia and Georgia’s economies are considered emerging/developing and are dependent on many different Russian imports. However, according to the European Bank for Reconstruction & Development, both economies are expected to grow 8% this year. Georgia’s economy has been recovering from the pandemic thanks to its burgeoning tourism industry, largely drawing Russian visitors. Additionally, in both Georgia and Armenia, the inflow of Russian businesses and tech professionals have boosted the economies.

A Brief Background

The three countries which encapsulate the region, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, were each republics under the Soviet Union until its fall in 1991. Additionally, the regions of Dagestan and Chechnya in Russia, also located in the geographic sphere of the Caucasus, each maintain a distinct identity from Russia. Both regions are majority ethnically non-Russian and still face regular violence over their power struggle with the regional heavyweight. In fact, many of the tensions in the region can be linked to Russian oppression, according to experts. In recent history, Russia invaded Georgia within hours of the kickoff of the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, sparking conflict in the Ossetia and Abkhazia regions. The Russo–Georgian War is considered the first European war of the 21st century. While the history of the Caucasus goes way back—for instance, the kingdom of Armenia dates back to the 331 BC—more recent events have been shaped by Cold War and subsequent fallout from the dissolution of the USSR.

The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

The tension over the Nagorno-Karabakh region began in the late 1980s and escalated into a full-scale war into the 1990s. In the early years of the conflict, approximately 30,000 people died. Since then, ceasefires and violence have arisen intermittently—with the most recent end to the fighting in 2020. At least 243 people have been killed since then. The conflict first began when newly independent Armenia demanded the region back from Azerbaijan, which was still a Soviet state at the time, as the population there was (and still is) mostly Armenian. Although not internationally recognized, a breakaway group has declared part of Nagorno-Karabakh as an independent state called the Republic of Artsakh. Here’s a very brief timeline:

1988-1994: First Nagorno-Karabakh War April 2016: Four days of violence at the separation line September-November 2020: War was reignited until Russia negotiated a ceasefire September 2022: New clashes erupted resulting in hundreds of deaths

The conflict has bled out into the region—Russia is on Armenia’s side and Turkey on Azerbaijan’s. But new allies may be taking the stage as evidenced by Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Armenia in mid-September. Today, the region is divided between Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Russian peacekeepers, but is still officially Azerbaijani. Editor’s note: A prior version of this article said that Russia’s 2008 invasion took place during the opening ceremonies of the Beijing Olympic Games. We have since adjusted this to “within hours of the kickoff” of the games, since the exact time varies according to sources. on After a year of casualties, structural devastation, and innumerable headlines, the conflict drags on. Many report the impacts to the economy, social demographics, and international relationships, but how do science and academia fair in the throes of war? Within the actions and responses of the conflict, we take a look at how six key scenarios globally shape science.

War’s Material Impacts to Science

1. Russia Invades Ukraine

The assault to research infrastructure in Ukraine is devastating. Approximately 27% of buildings are damaged or destroyed. The country’s leading scientific research centers, like the Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology, or the world’s largest decameter-wavelength radio telescope, are in ruins. While the majority of research centers remain standing, many are not operating. Amidst rolling blackouts and disruptions, a dramatic decrease in research funds (as large as 50%) has cut back scientific activity in the country. Rebuilding efforts are underway, but the extent to which it will return to its former capacity remains to be seen.

2. Ukraine Fights Back

As research funds have been redirected to the military, and scientists, too, have pivoted in a similar way. Martial law and general mobilization have enlisted male researchers, especially those with military experience and those within the 18-60 age range. Women were exempt until July 2022. Those with degrees in chemistry, biology, and telecommunications were required to enter the military registry. For both men and women researchers alike, these requirements meant staying in the country for the remainder of the year. Extensions for mobilization have subsided as of February 19th, 2023.

Social Impacts of War to Science

3. Western Leaders Exclude Russia

One year ago, scientists and institutions around the world immediately launched into protest against Russia’s escalation:

The European Commission agreed to cease payments to Russian participants and to not renew contract agreements for Horizon Europe The $300-million, MIT-led Skoltech program was dissolved one day after the war began, with no foreseeable restart in the future Various governments and research councils in the European Union froze collaborations and discouraged working with Russian institutions The European Organization for Nuclear Research, CERN, barred all Russian observers and will dismiss almost 8% of its workers—about 1,000 Russian scientists—hen contracts expire later this year

These condemnations, and more, remain in effect today and are emboldened by what has come to be known as a “scientific boycott”. Journal publishers around the world imposed some of their own sanctions on Russian institutions and scientists in light of this boycott. These range from prohibiting Russian manuscript submissions (Elsevier’s Journal of Molecular Structure) to scrubbing journal indices of Russian papers and authors.

4. Russia Dissociates from the West

As a response to the sanctions imposed on the Russian economy, Russia ceases to sell natural gas to most of Europe. Institutions are reassessing their usage and dependence on Russian energy, but alternatives are not yet affordable. The German Electron Synchrotron (DESY) in Hamburg, home to the world’s most powerful X-ray laser, is struggling with rising electricity costs. CERN, for instance, has already cut its data collection for the year by two weeks in order to save money. This makes it difficult for pre-war projects to continue collaborating with Russia. As a result, there are questions about how withdrawals may be affecting Russian science, too. For now, that remains relatively unknown, though some have guesses. Young scientists, many barred from attending international conferences and meetings, may seek employment or opportunity elsewhere to develop their careers. Some speculate a “brain drain” effect may occur, similar to the academic fallout of the Soviet Union’s collapse in the 1990s. How Russia will participate in pre-war international research collaborations is still unknown. For now, a number of pre-war projects ranging from the Arctic to the fire-prone wilds of northern Russia are on hold. All of these scenarios paint a concerning picture about the progress of research. There are indications that Russian scientific collaboration may already be shifting eastward.

Philanthropic Impacts of War to Science

5. New Homes for Ukrainian Science

Finding support for Ukrainians emigrating from the conflict is difficult, but not impossible. Though many Ukrainians scientists remain in the country making the best of a difficult situation, approximately 6,000 are now living abroad. Most Ukrainian emigrants are now living in Poland and Germany. Some scientists continue to work remotely, supporting projects at their home institutions or with new research programs they’ve found since relocating. These success stories are thanks to the work of a number of ad-hoc mobilizations that help keep researchers working in the European cooperation. Groups like MSC4Ukraine help postdoc students and researchers find new opportunities across Europe. Social media trends like #Science4Ukraine help connect researchers to other supportive movements.

6. The International Rebuilding of Ukrainian Science

Various research institutions have also lent support to the survival and rebuilding of science in Ukraine:

The largest science prize, the Breakthrough Prize, recently donated $3 million to fund research programs and reconstruction efforts Federal research councils, like those in Netherlands and Switzerland, also have programs to formally support displaced scientists and researchers The European Union is investigating new funding schemes that could repurpose almost €320 billion of frozen Russian Federal Reserves

No Consensus on Boycott

While the Western front seems united in it’s condemnation of the war, the international science community isn’t in total agreement with a science boycott. Some scientists argue that excluding Russian scientists—especially those who have vocalized their disdain for the war—serves to punish unrelated individuals. This fractures the benefits of international scientific exchange. Others, especially those in countries who are economically dependent on Russia, have remained silent or even supported the invasion. In these cases, Russia’s science initiatives may lean more heavily in their direction. It’s easy to appreciate how war complicates many different angles of the global research ecosystem. After one year, how things will turn out remains a mystery. But one thing is for certain: science adapts and progresses even in the bleakest times. For now, supporting all efforts to reduce conflict remains in science’s best interests. Full sources here