Between ongoing armed conflicts to building of defenses preemptively, many countries have amassed significant militaries to date. This map, using data from World Population Review, displays all the world’s military personnel.

Who Has the Largest Military?

So who has the largest military? Well, the answer isn’t so simple. There are three commonly measured categories of military personnel:

Active military: Soldiers who work full-time for the army Country with the largest active military: 🇨🇳 China (over 2 million) Military reserves: People who do not work for the army full-time, but have military training and can be called up and deployed at any moment Country with the largest military reserves: 🇻🇳 Vietnam (5 million) Paramilitary: Groups that aren’t officially military but operate in a similar fashion, such as the CIA or SWAT teams in the U.S. Country with the largest paramilitary: 🇰🇵 North Korea (an estimated 5 million)

NOTE: Of these categories of military personnel, paramilitary is the least well-defined across the world’s countries and thus not included in the infographic above. Which country has the biggest military? It depends who’s doing the counting. If we include paramilitary forces, here’s how the top countries stack up in terms of military personnel: Source: World Population Review When combining all three types of military, Vietnam comes out on top with over 10 million personnel. And here are the world’s top 10 biggest militaries, excluding paramilitary forces:

Building up Military Personnel

The reasons for these immense military sizes are obvious in some cases. For example, in Vietnam, North Korea, and Russia, citizens are required to serve a mandatory period of time for the military. The Koreas, two countries still technically at war, both conscript citizens for their armies. In North Korea, boys are conscripted at age 14. They begin active service at age 17 and remain in the army for another 13 years. In select cases, women are conscripted as well. In South Korea, a man must enlist at some point between the ages of 18 and 28. Most service terms are just over one year at minimum. There are however, certain exceptions: the K-Pop group BTS was recently granted legal rights to delay their military service, thanks to the country’s culture minister. Here’s a look at just a few of the other countries that require their citizens to serve some form of military service:

🇦🇹 Austria 🇧🇷 Brazil 🇲🇲 Myanmar 🇪🇬 Egypt 🇮🇱 Israel 🇺🇦 Ukraine

In many of these countries, geopolitical and historical factors play into why they have mandatory service in place. In the U.S., many different factors play into why the country has such a large military force. For one, the military industrial complex feeds into the U.S. army. A longstanding tradition of the American government and the defense and weapons industry working closely together creates economic incentives to build up arms and defenses, translating into a need for more personnel. Additionally, the U.S. army offers job security and safety nets, and can be an attractive career choice. Culturally, the military is also held in high esteem in the country.

Nations with No Armies

For many countries, building up military personnel is a priority, however, there are other nations who have no armies at all (excluding the paramilitary branch). Here’s a glance at some countries that have no armies:

🇨🇷 Costa Rica 🇮🇸 Iceland 🇱🇮 Liechtenstein 🇵🇦 Panama

Costa Rica has no army as it was dissolved after the country’s civil war in the 1940s. The funds for the military were redirected towards other public services, such as education. This is not to say that these nations live in a state of constant peace—most have found alternative means to garner security forces. Under the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance, other countries like the U.S. are technically obligated to provide military services to Costa Rica, for example, should they be in need.

The Future of Warfare

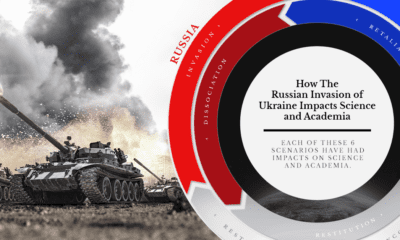

International conflicts persist in the 21st century, but now go far beyond just the number of troops on the ground. New and emerging forms of warfare pose unforeseen threats. For example, cyber warfare and utilization of data to attack populations could dismantle countries and cause conflict almost instantaneously. Cybersecurity failure has been ranked among the top 10 most likely risks to the world today. If current trends continue, soldiers of the future will face off on very different fields of battle. on After a year of casualties, structural devastation, and innumerable headlines, the conflict drags on. Many report the impacts to the economy, social demographics, and international relationships, but how do science and academia fair in the throes of war? Within the actions and responses of the conflict, we take a look at how six key scenarios globally shape science.

War’s Material Impacts to Science

1. Russia Invades Ukraine

The assault to research infrastructure in Ukraine is devastating. Approximately 27% of buildings are damaged or destroyed. The country’s leading scientific research centers, like the Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology, or the world’s largest decameter-wavelength radio telescope, are in ruins. While the majority of research centers remain standing, many are not operating. Amidst rolling blackouts and disruptions, a dramatic decrease in research funds (as large as 50%) has cut back scientific activity in the country. Rebuilding efforts are underway, but the extent to which it will return to its former capacity remains to be seen.

2. Ukraine Fights Back

As research funds have been redirected to the military, and scientists, too, have pivoted in a similar way. Martial law and general mobilization have enlisted male researchers, especially those with military experience and those within the 18-60 age range. Women were exempt until July 2022. Those with degrees in chemistry, biology, and telecommunications were required to enter the military registry. For both men and women researchers alike, these requirements meant staying in the country for the remainder of the year. Extensions for mobilization have subsided as of February 19th, 2023.

Social Impacts of War to Science

3. Western Leaders Exclude Russia

One year ago, scientists and institutions around the world immediately launched into protest against Russia’s escalation:

The European Commission agreed to cease payments to Russian participants and to not renew contract agreements for Horizon Europe The $300-million, MIT-led Skoltech program was dissolved one day after the war began, with no foreseeable restart in the future Various governments and research councils in the European Union froze collaborations and discouraged working with Russian institutions The European Organization for Nuclear Research, CERN, barred all Russian observers and will dismiss almost 8% of its workers—about 1,000 Russian scientists—hen contracts expire later this year

These condemnations, and more, remain in effect today and are emboldened by what has come to be known as a “scientific boycott”. Journal publishers around the world imposed some of their own sanctions on Russian institutions and scientists in light of this boycott. These range from prohibiting Russian manuscript submissions (Elsevier’s Journal of Molecular Structure) to scrubbing journal indices of Russian papers and authors.

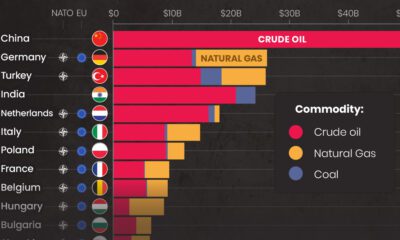

4. Russia Dissociates from the West

As a response to the sanctions imposed on the Russian economy, Russia ceases to sell natural gas to most of Europe. Institutions are reassessing their usage and dependence on Russian energy, but alternatives are not yet affordable. The German Electron Synchrotron (DESY) in Hamburg, home to the world’s most powerful X-ray laser, is struggling with rising electricity costs. CERN, for instance, has already cut its data collection for the year by two weeks in order to save money. This makes it difficult for pre-war projects to continue collaborating with Russia. As a result, there are questions about how withdrawals may be affecting Russian science, too. For now, that remains relatively unknown, though some have guesses. Young scientists, many barred from attending international conferences and meetings, may seek employment or opportunity elsewhere to develop their careers. Some speculate a “brain drain” effect may occur, similar to the academic fallout of the Soviet Union’s collapse in the 1990s. How Russia will participate in pre-war international research collaborations is still unknown. For now, a number of pre-war projects ranging from the Arctic to the fire-prone wilds of northern Russia are on hold. All of these scenarios paint a concerning picture about the progress of research. There are indications that Russian scientific collaboration may already be shifting eastward.

Philanthropic Impacts of War to Science

5. New Homes for Ukrainian Science

Finding support for Ukrainians emigrating from the conflict is difficult, but not impossible. Though many Ukrainians scientists remain in the country making the best of a difficult situation, approximately 6,000 are now living abroad. Most Ukrainian emigrants are now living in Poland and Germany. Some scientists continue to work remotely, supporting projects at their home institutions or with new research programs they’ve found since relocating. These success stories are thanks to the work of a number of ad-hoc mobilizations that help keep researchers working in the European cooperation. Groups like MSC4Ukraine help postdoc students and researchers find new opportunities across Europe. Social media trends like #Science4Ukraine help connect researchers to other supportive movements.

6. The International Rebuilding of Ukrainian Science

Various research institutions have also lent support to the survival and rebuilding of science in Ukraine:

The largest science prize, the Breakthrough Prize, recently donated $3 million to fund research programs and reconstruction efforts Federal research councils, like those in Netherlands and Switzerland, also have programs to formally support displaced scientists and researchers The European Union is investigating new funding schemes that could repurpose almost €320 billion of frozen Russian Federal Reserves

No Consensus on Boycott

While the Western front seems united in it’s condemnation of the war, the international science community isn’t in total agreement with a science boycott. Some scientists argue that excluding Russian scientists—especially those who have vocalized their disdain for the war—serves to punish unrelated individuals. This fractures the benefits of international scientific exchange. Others, especially those in countries who are economically dependent on Russia, have remained silent or even supported the invasion. In these cases, Russia’s science initiatives may lean more heavily in their direction. It’s easy to appreciate how war complicates many different angles of the global research ecosystem. After one year, how things will turn out remains a mystery. But one thing is for certain: science adapts and progresses even in the bleakest times. For now, supporting all efforts to reduce conflict remains in science’s best interests. Full sources here