Megacity 2020: The Pearl River Delta’s Astonishing Growth

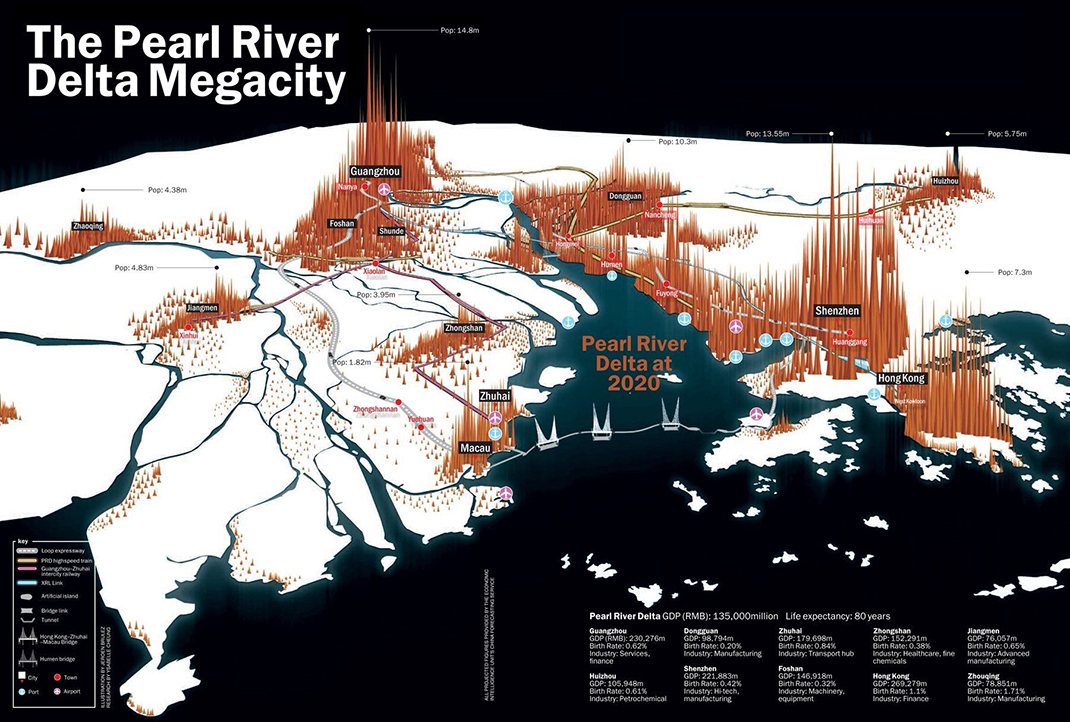

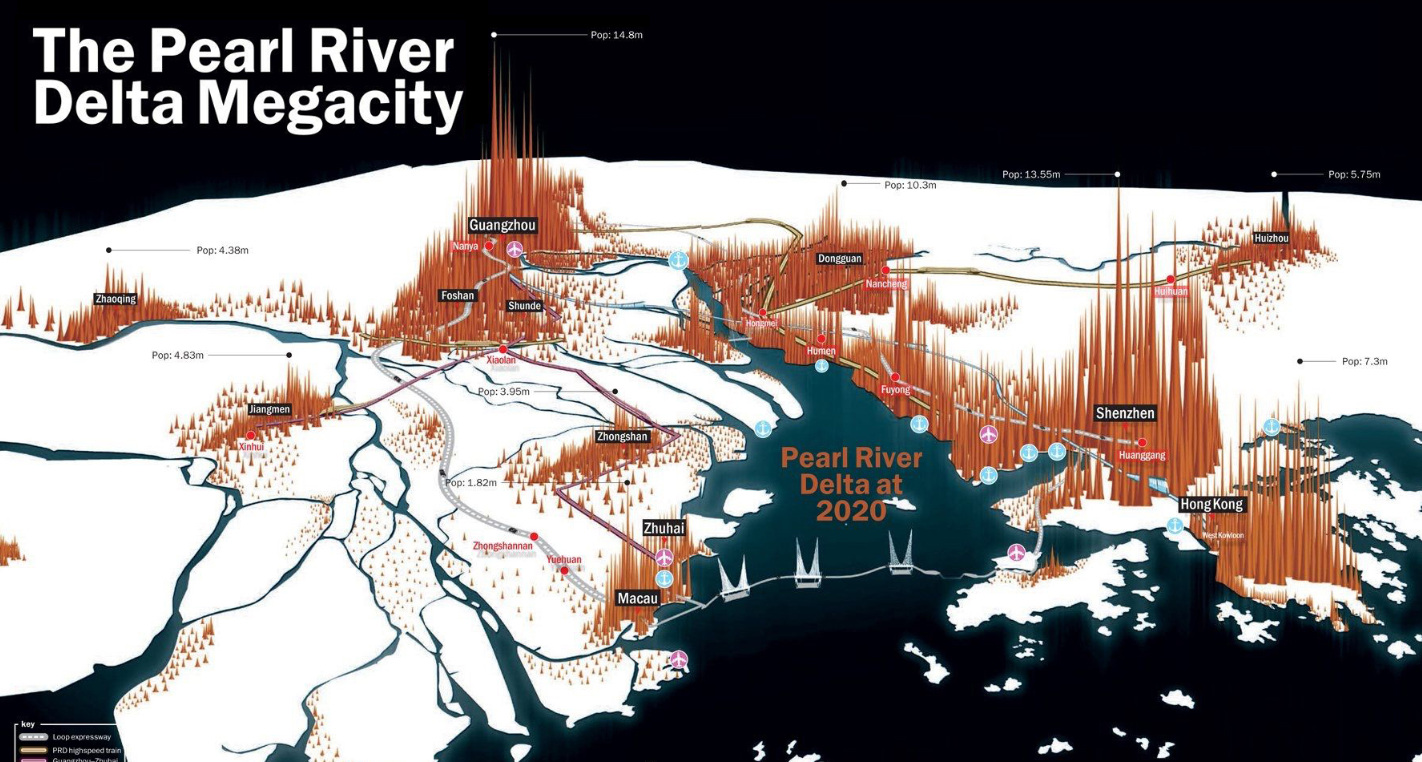

View the high resolution version of today’s graphic by clicking here. In the late 1970s, the fertile river delta to the north of Hong Kong’s territory was primarily agricultural land. Shenzhen was an unassuming town of 30,000 people – with only one functioning taxi – and China was still very much a communist, rural country. As the visualization above, by Time Out Hong Kong, demonstrates, the sleepy Pearl River Delta was on the cusp of an unprecedented growth spurt that would see cities expand and merge to become the largest contiguous urban region in the world.

A trickle becomes a flood

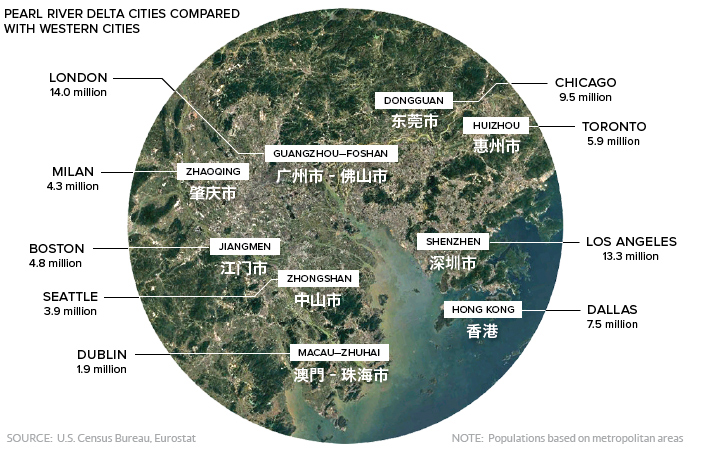

In 1979, the Chinese government – led by Deng Xiaoping – created four Special Economic Zones (SEZ) with the intention of attracting foreign direct investment and encouraging private enterprise. The designation of Shenzhen and Zhuhai as SEZs was a strategic move to act as an “overflow” for businesses in Hong Kong, and the impact on the Pearl River Delta was profound and immediate. A number of factors also helped contribute to the meteoric rise of the region: proximity to Hong Kong’s financial sector, a world-class seaport, a huge and inexpensive labor pool, cheap and abundant land, and few regulatory impediments to rapidly growing companies. In the two decades after Deng Xiaoping’s market reforms, the GDP of the region grow by more than 10x and urbanization – bolstered by large-scale infrastructure projects – began in earnest. To put the scale of this population clustering into perspective, here are the populations of cities within the Pearl River Delta in 2020 compared with modern-day metropolitan areas in North America and Europe:

Today, this compact region has a GDP equivalent to that of South Korea.

Megalopolis at the Gates

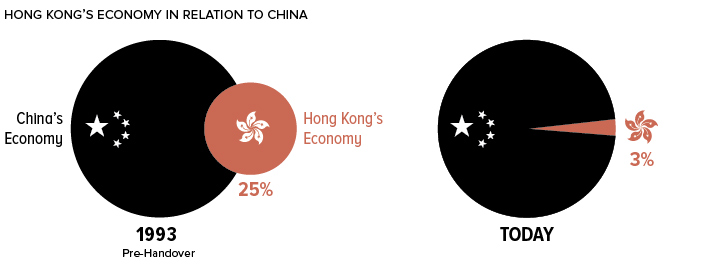

The explosive growth the Pearl River Delta has upended the regional balance of power. At the close of the 20th century, Hong Kong was the undisputed economic powerhouse of the region. In fact, just prior to the handover from the United Kingdom to China, the city’s economic output was equal to a quarter of China’s entire GDP.

Today, the situation is markedly different. Hong Kong is no longer a separate entity, and its GDP represents a mere 3% of China’s. This shift in the regional dynamic is causing trepidation in Hong Kong, where over 90% of the millennial population identifies as “Hong Konger” as opposed to “Chinese”. Although the government has agreed in spirit to maintain the city’s autonomy until 2047, recent actions suggest an eagerness to integrate the entire region into a seamless megacity. The blurring of the lines appears to be well underway, as more than half a million people from the city now reside in Mainland China, up from approximately 150,000 a decade ago. One physical manifestation of Mainland China’s push for an integrated region is the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge. This colossal infrastructure project is a 31 mile (50 km) connection that includes bridges, tunnels, and three man-made islands. In China, where each project is more ambitious than the next, it’s only fitting that the world’s largest urban area will be connected by the world’s largest sea crossing.

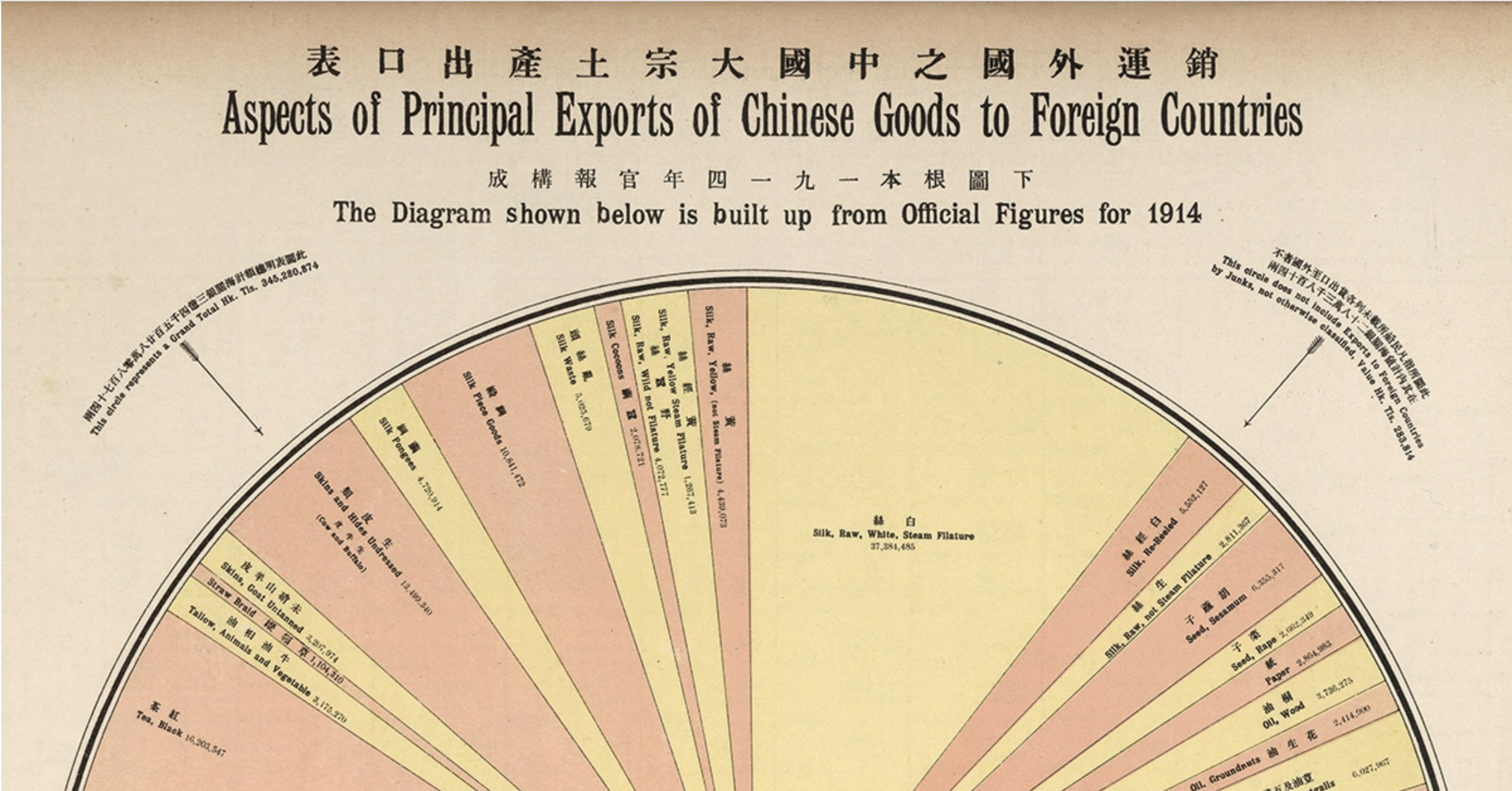

on A statement that is as profound as it is banal. In other words, when we do history, we’re a bit like tourists. If we really want to understand the past, we have to think like a local. The infographic above, Aspects of Principal Exports of Chinese Goods to Foreign Countries, is the first in a series that we’re calling Vintage Viz, which presents a historical visualization along with the background and analytical tools to make sense of it. Today, the People’s Republic of China is the second largest economy in the world, a permanent member of the UN Security Council, and a growing military power. But at the dawn of the 20th century, things were much, much different.

Opium and the Opening of China to the West

Early Sino-Western trade was restricted by the Qing emperors to three ports, and after 1757, just one, in what became known as the Canton System. This name came from the one remaining port city of the same name, present-day Guangzhou. Foreign trade was tightly monitored and subject to stiff tariffs, and Western traders chafed under these restrictions. So when in 1839, Chinese authorities moved to shut down opium smuggling—an important source of profit for foreign merchants—Western powers saw their chance and used the pretext to revise the terms of trade by force. In what became known as the Opium Wars, 1839-1842 and 1856-1860, first Great Britain and then an Anglo-French alliance defeated imperial China and imposed punitive treaties that included indemnities and lowered tariffs, but also expanded the number of ports open to foreign traders, first to five and by 1911, to more than 50.

Westerners were exempted from local laws, Christian missionaries were allowed to proselytize freely, and the opium trade was legalized. Hong Kong was also ceded to Great Britain at this time. The Treaty Port Era, also known as the Century of Humiliation, was perhaps too much for the country to bear. The weakened central government was beset by popular unrest, including the Taiping Rebellion (1850–64), which killed 20 million people, and the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901), so-named for the secret society that led the movement, the Righteous and Harmonious Fists. Eventually, the last Chinese emperor was deposed and a republic declared in 1911. Nevertheless, the government was too weak to impose its will, and was repeatedly challenged by warlords. So as we approach the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, and the period covered by our visualization, we find China weakened internally by civil strife, and externally by Western powers.

The History of this Century-Old Pie Chart

Aspects of Principal Exports of Chinese Goods to Foreign Countries captures Chinese exports for 1914, and comes from The New Atlas and Commercial Gazetteer of China: A Work Devoted to Its Geography & Resources and Economic & Commercial Development. Originally published in 1917 and edited by Edwin J. Dingle for the Far Eastern Geographical Establishment, the volume contains a wealth of data for the period. According to the book’s Preface, it “seeks to give all the information that is essential to the business-man in regard to a country… about which less is known than in regard to any similar area in the world.” The visualization breaks down total Chinese exports for 1914 in haikwan taels (hk. tls.), a unit of silver currency used to collect tariffs. In 1907, one haikwan tael was worth $0.79 U.S. dollars. Official figures come from the Chinese Maritime Customs Service. This was set up by foreign consuls after the First Opium War to collect tariffs to guarantee the payment of treaty indemnities. Exports in 1914 represented 345 million hk. tls., a 14.4% decrease from 1913, likely owing to the outbreak of the First World War that same year. Apart from “Other Metals and Minerals, Sundries, etc,” which served as a catch-all category, the largest categories were silks and teas of various types, representing 22.6% and 10.4% of total exports respectively. Below are some more details that emerge from this visualization.

All the Tea in China

The Chinese tea trade was the subject of another visualization in the Atlas. It shows that China had been steadily losing ground to British India. Between 1888-1892 Chinese exports to Great Britain were 242 million pounds against India’s 105 million pounds. By 1912-1913, India had surpassed China to export 279 million pounds against 198 million pounds. In 1914, the majority of Chinese exports went to Russia, 902,716 piculs in all. A picul is equal to “as much as a man can carry on a shoulder-pole” or about 133 pounds.

The Silk Road to Profits

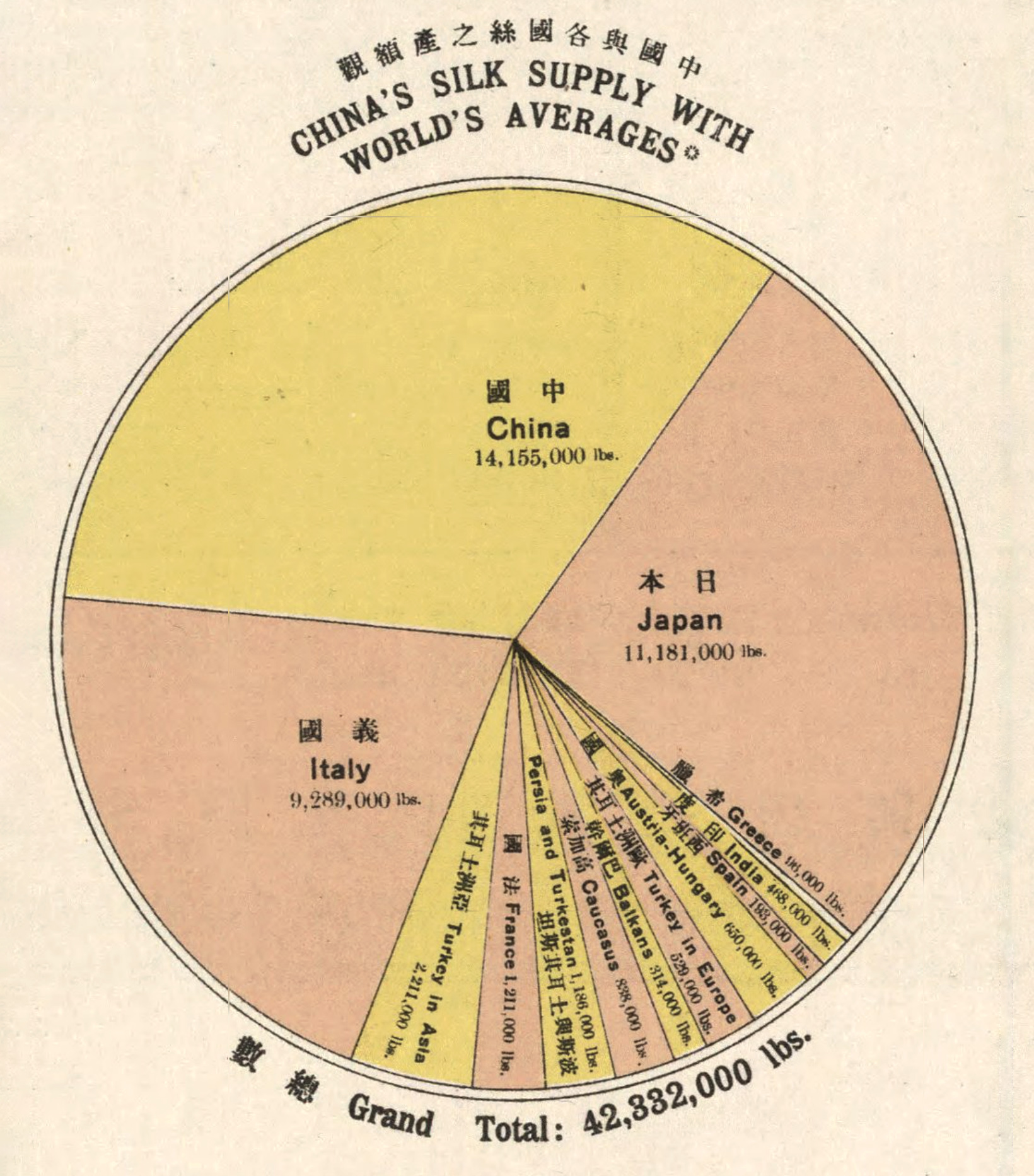

Silk has long been in demand in the West as a luxury good, giving its name to the overland trade route that connected East and West for centuries: the Silk Road. In 1914, China was the largest producer and exporter of silks in the world. On an annual basis, China averaged 14 million pounds, compared to the number two spot, Japan, at 11 million pounds, and number three, Italy, at 9 million pounds. Together, these three controlled 81.7% of the global silk trade.

The Opium of the Masses?

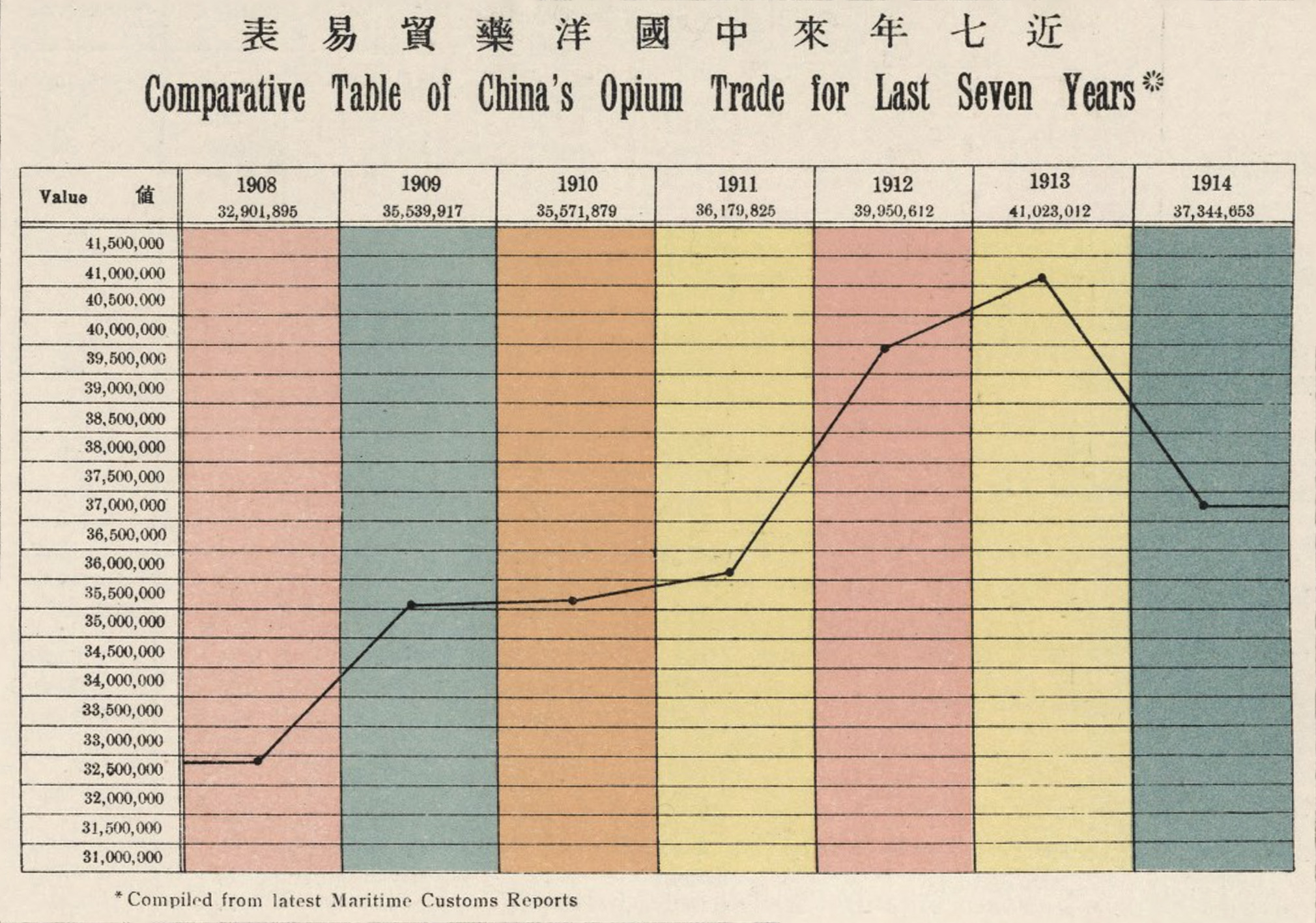

The opium trade, the pretext that opened China to foreign trade, was still big money in 1914. A total of 37 million hk. tls. were imported in 1914 from India, up 11.9% from 1908. This is actually down from a peak of 41 million hk. tls. in 1913.

In 1907, China signed the Ten Year Agreement with India, which ultimately phased out the opium trade. By 1917 the trade was all but extinguished.

Back to the Future

The Aspects of Principal Exports of Chinese Goods to Foreign Countries is a far cry from the contemporary trade picture. China’s top export in 2021 was in the category “telephones for cellular networks or other wireless networks,” and was worth $147.1 billion. But it’s worth noting that China today is a direct result of this period. The resentment created during the Century of Humiliation would eventually help lead to Mao Zedong, the Long March, and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. And in 1979, the Chinese central government would set up the first of their own “treaty ports,” in the form of special economic zones, places where foreign companies could set up shop. But this time, it wasn’t foreign powers who were making the rules.