This animated Chart of the Week visualizes 10 years of global competitiveness, according to the World Economic Forum, and tracks how rankings have changed in this time.

How Do You Measure Competition?

The WEF’s annual Global Competitiveness Report defines the concept of ‘competitiveness’ as an economy’s productivity—and the institutions, policies, and factors which shape this. This year’s edition unpacks the national competitiveness of 141 countries, using the newly-introduced Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) 4.0 which looks at four key metrics:

The Most Competitive: Movers and Shakers

The world’s top countries excel in many fields—but there can only be one #1. In 2019, Singapore wins the coveted “most competitive economy” title, with a 84.8 score on the GCI. The nation’s developed infrastructure, health, labor market, and financial system have all propelled it forward—swapping with the U.S. (83.7) for the top spot. However, more can be done, as the report notes Singapore still lacks press freedom and demonstrates a low commitment to sustainability. How have the current scores of the most competitive economies improved or fallen behind, compared to 2018? Finland (80.2) and Canada (79.6) are notable exits from this top 10 list over the years. Meanwhile, Denmark (81.2) disappeared from the rankings for five years, but managed to climb back up in 2018.

Regional Competitiveness: Highs and Lows

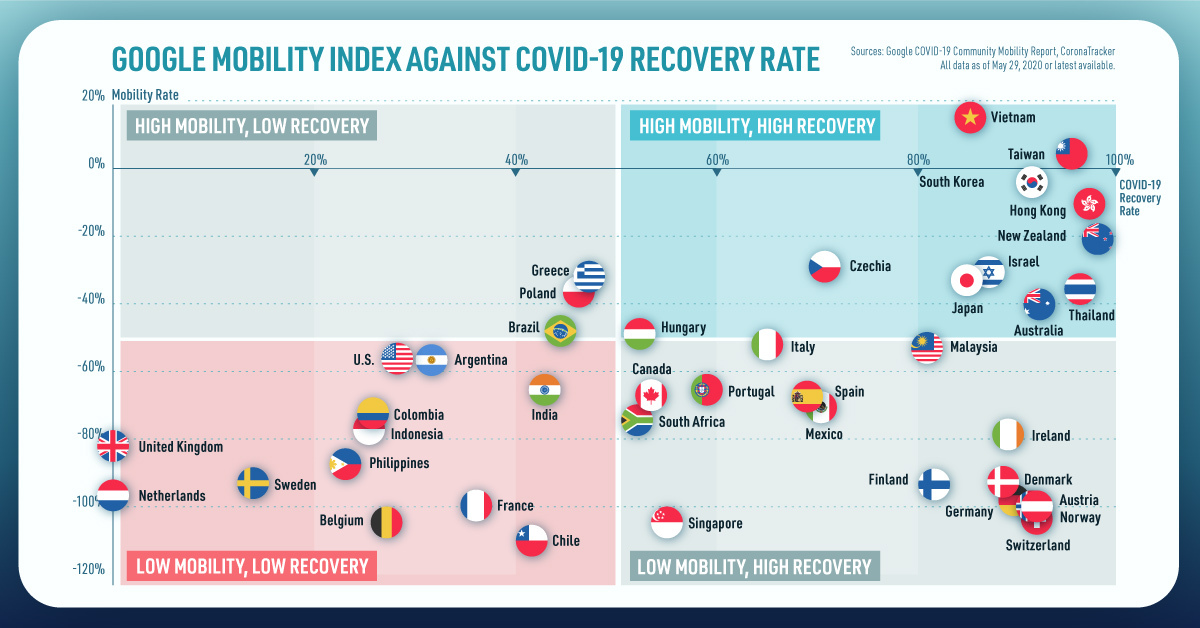

Another perspective on the most competitive economies is to look at how countries fare within regions, and how these regions compete among each other. Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has the widest gap in competitiveness scores—Israel (76.7) scores over double that of poorest-performing Yemen (35.5). Interestingly, the MENA region showed the most progress, growing its median score by 2.77% between 2018-2019. The narrowest gap is actually in South Asia, with just a single-digit difference between India (61.4) and Nepal (51.6). However, the region also grew the slowest, with only 0.08% increase in median score over a year. Across all regions, the WEF found that East Asia’s 73.9 median score was the highest. Europe and North America were not far behind with a 70.9 median score. This is consistent with the fact that the most competitive economies have all come from these regions in the past decade. As all these countries race towards the frontier—an ideal state where productivity growth is not constrained—the report notes that competitiveness “does not imply a zero-sum game”. Instead, any and all countries are capable of improving their productivity according to the GCI measures. on Today’s chart measures the extent to which 41 major economies are reopening, by plotting two metrics for each country: the mobility rate and the COVID-19 recovery rate: Data for the first measure comes from Google’s COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports, which relies on aggregated, anonymous location history data from individuals. Note that China does not show up in the graphic as the government bans Google services. COVID-19 recovery rates rely on values from CoronaTracker, using aggregated information from multiple global and governmental databases such as WHO and CDC.

Reopening Economies, One Step at a Time

In general, the higher the mobility rate, the more economic activity this signifies. In most cases, mobility rate also correlates with a higher rate of recovered people in the population. Here’s how these countries fare based on the above metrics. Mobility data as of May 21, 2020 (Latest available). COVID-19 case data as of May 29, 2020. In the main scatterplot visualization, we’ve taken things a step further, assigning these countries into four distinct quadrants:

1. High Mobility, High Recovery

High recovery rates are resulting in lifted restrictions for countries in this quadrant, and people are steadily returning to work. New Zealand has earned praise for its early and effective pandemic response, allowing it to curtail the total number of cases. This has resulted in a 98% recovery rate, the highest of all countries. After almost 50 days of lockdown, the government is recommending a flexible four-day work week to boost the economy back up.

2. High Mobility, Low Recovery

Despite low COVID-19 related recoveries, mobility rates of countries in this quadrant remain higher than average. Some countries have loosened lockdown measures, while others did not have strict measures in place to begin with. Brazil is an interesting case study to consider here. After deferring lockdown decisions to state and local levels, the country is now averaging the highest number of daily cases out of any country. On May 28th, for example, the country had 24,151 new cases and 1,067 new deaths.

3. Low Mobility, High Recovery

Countries in this quadrant are playing it safe, and holding off on reopening their economies until the population has fully recovered. Italy, the once-epicenter for the crisis in Europe is understandably wary of cases rising back up to critical levels. As a result, it has opted to keep its activity to a minimum to try and boost the 65% recovery rate, even as it slowly emerges from over 10 weeks of lockdown.

4. Low Mobility, Low Recovery

Last but not least, people in these countries are cautiously remaining indoors as their governments continue to work on crisis response. With a low 0.05% recovery rate, the United Kingdom has no immediate plans to reopen. A two-week lag time in reporting discharged patients from NHS services may also be contributing to this low number. Although new cases are leveling off, the country has the highest coronavirus-caused death toll across Europe. The U.S. also sits in this quadrant with over 1.7 million cases and counting. Recently, some states have opted to ease restrictions on social and business activity, which could potentially result in case numbers climbing back up. Over in Sweden, a controversial herd immunity strategy meant that the country continued business as usual amid the rest of Europe’s heightened regulations. Sweden’s COVID-19 recovery rate sits at only 13.9%, and the country’s -93% mobility rate implies that people have been taking their own precautions.

COVID-19’s Impact on the Future

It’s important to note that a “second wave” of new cases could upend plans to reopen economies. As countries reckon with these competing risks of health and economic activity, there is no clear answer around the right path to take. COVID-19 is a catalyst for an entirely different future, but interestingly, it’s one that has been in the works for a while. —Carmen Reinhart, incoming Chief Economist for the World Bank Will there be any chance of returning to “normal” as we know it?