Six Problems Facing Driverless Cars and Their Track Record

Driverless car technology is here to stay. Their track record so far is very impressive with Google cars driving over a million miles since 2009. During that time, 13 accidents have been recorded, but all of them were caused by other drivers or by human intervention. The robots themselves have been virtually flawless. Right now, various vehicle manufacturers (Mercedes-Benz, General Motors, Toyota, Tesla, Audi, and more) have already built prototypes of driverless cars, and tech companies (Google, Uber, and potentially even Apple) are working on similar ambitions. However, human nature seems to be innately suspicious of robots and artificial intelligence. Whether we’re talking about Skynet from “The Terminator” or Elon Musk’s concerns about AI, it’s clear that there will always be some pushback towards these kinds of ideas. It may take decades to convince people that autonomous cars will solve more problems than they create. For these reasons, regulations around driverless cars are likely to move forward with a speed rivaling that of molasses. Policy makers do not want to be held responsible for potential hiccups, and much of the populace that is not in Silicon Valley will be slow to embrace ideas that could change the entire status quo. Beyond general human suspicion of robots, there are some legitimate obstacles that need to be solved before driverless cars become a reality. Today’s infographic highlights some of these issues that need to be addressed: Firstly, driverless cars struggle to identify humans alongside the vehicle or walking in front of them. This could lead to situations where they fail to see police officers, pedestrians, or workers on the side of construction zones giving instructions. Next, autonomous cars have a tough time in bad weather conditions in which an entire new array of problems are created for the algorithms to solve. Driving in Silicon Valley may be relatively straightforward, but what happens when a car encounters a snow storm in the Northeast, or torrential rainfall in the tropics? It is also not a surprise that making decisions based on morality, ethics, and the law are also problems for robots. When a car needs to make a decision between running over a pedestrian, and getting rear-ended from behind, what does it do? Further, who is accountable in a situation where a car performs an emergency stop where it stops as fast as possible, but still hits another person or vehicle? There are also some conflicting directives that may hinder decision-making by autonomous vehicles. They have a directive to avoid collisions with objects, but also to obey the law by staying in lanes. At what point, if ever, does one of these directives override the other? Lastly, even with the above issues and regulations sorted, cost is going to continue to be preventative measure for many consumers. Even in 2025, it will cost up to an extra $10k in vehicle add-ons to allow for driverless software and hardware. This is expected to decrease as time goes on, with costs dropping to roughly $3k in 2035. The good news for driverless technology is that most of the problems highlighted in today’s infographic can be overcome with more research and time. Even with these issues identified, autonomous cars are still driving today with relatively flawless track records compared to human-controlled vehicles. They eliminate human error, which is the cause of most accidents: robots don’t drive under the influence, use unnecessary speed, or get distracted by text messages. The bad news for the technology? If you thought the lobby against Uber was strong, wait until all truck drivers, taxi drivers, public transit employees, and limousine drivers are collectively put up against a wall. Original graphic by: ClickMechanic

on But fast forward to the end of last week, and SVB was shuttered by regulators after a panic-induced bank run. So, how exactly did this happen? We dig in below.

Road to a Bank Run

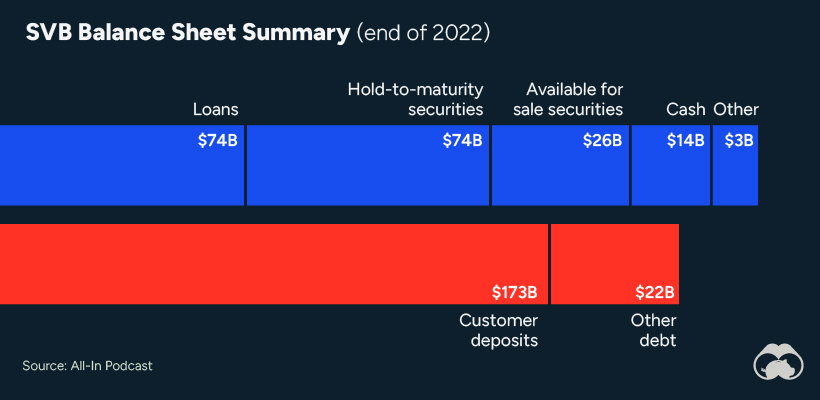

SVB and its customers generally thrived during the low interest rate era, but as rates rose, SVB found itself more exposed to risk than a typical bank. Even so, at the end of 2022, the bank’s balance sheet showed no cause for alarm.

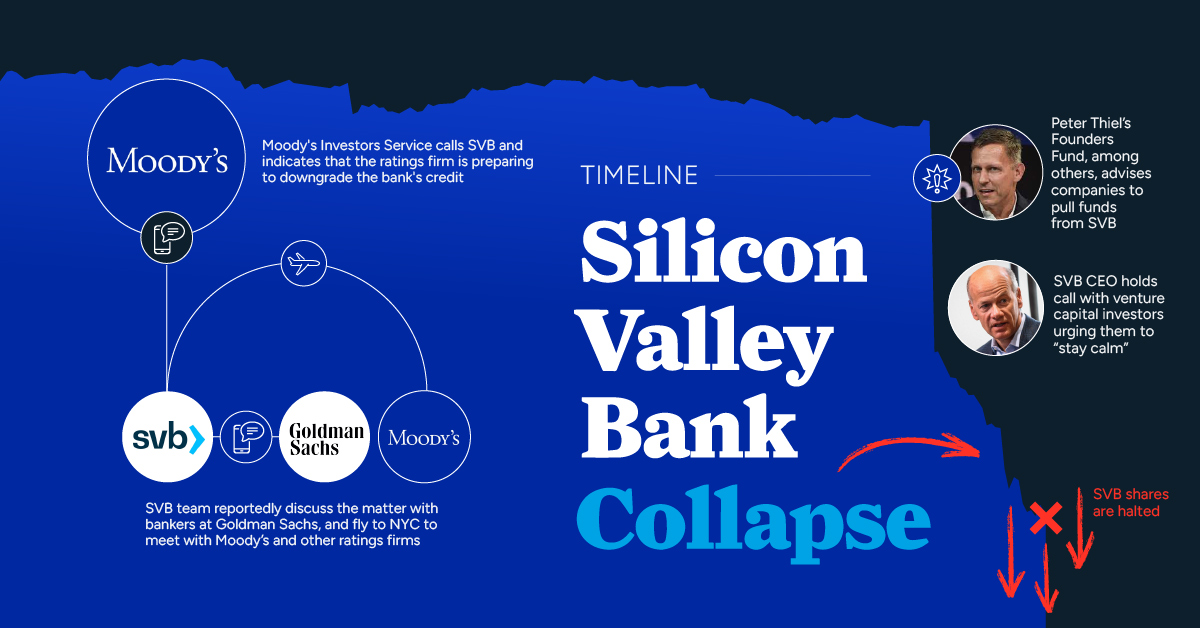

As well, the bank was viewed positively in a number of places. Most Wall Street analyst ratings were overwhelmingly positive on the bank’s stock, and Forbes had just added the bank to its Financial All-Stars list. Outward signs of trouble emerged on Wednesday, March 8th, when SVB surprised investors with news that the bank needed to raise more than $2 billion to shore up its balance sheet. The reaction from prominent venture capitalists was not positive, with Coatue Management, Union Square Ventures, and Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund moving to limit exposure to the 40-year-old bank. The influence of these firms is believed to have added fuel to the fire, and a bank run ensued. Also influencing decision making was the fact that SVB had the highest percentage of uninsured domestic deposits of all big banks. These totaled nearly $152 billion, or about 97% of all deposits. By the end of the day, customers had tried to withdraw $42 billion in deposits.

What Triggered the SVB Collapse?

While the collapse of SVB took place over the course of 44 hours, its roots trace back to the early pandemic years. In 2021, U.S. venture capital-backed companies raised a record $330 billion—double the amount seen in 2020. At the time, interest rates were at rock-bottom levels to help buoy the economy. Matt Levine sums up the situation well: “When interest rates are low everywhere, a dollar in 20 years is about as good as a dollar today, so a startup whose business model is “we will lose money for a decade building artificial intelligence, and then rake in lots of money in the far future” sounds pretty good. When interest rates are higher, a dollar today is better than a dollar tomorrow, so investors want cash flows. When interest rates were low for a long time, and suddenly become high, all the money that was rushing to your customers is suddenly cut off.” Source: Pitchbook Why is this important? During this time, SVB received billions of dollars from these venture-backed clients. In one year alone, their deposits increased 100%. They took these funds and invested them in longer-term bonds. As a result, this created a dangerous trap as the company expected rates would remain low. During this time, SVB invested in bonds at the top of the market. As interest rates rose higher and bond prices declined, SVB started taking major losses on their long-term bond holdings.

Losses Fueling a Liquidity Crunch

When SVB reported its fourth quarter results in early 2023, Moody’s Investor Service, a credit rating agency took notice. In early March, it said that SVB was at high risk for a downgrade due to its significant unrealized losses. In response, SVB looked to sell $2 billion of its investments at a loss to help boost liquidity for its struggling balance sheet. Soon, more hedge funds and venture investors realized SVB could be on thin ice. Depositors withdrew funds in droves, spurring a liquidity squeeze and prompting California regulators and the FDIC to step in and shut down the bank.

What Happens Now?

While much of SVB’s activity was focused on the tech sector, the bank’s shocking collapse has rattled a financial sector that is already on edge.

The four biggest U.S. banks lost a combined $52 billion the day before the SVB collapse. On Friday, other banking stocks saw double-digit drops, including Signature Bank (-23%), First Republic (-15%), and Silvergate Capital (-11%).

Source: Morningstar Direct. *Represents March 9 data, trading halted on March 10.

When the dust settles, it’s hard to predict the ripple effects that will emerge from this dramatic event. For investors, the Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen announced confidence in the banking system remaining resilient, noting that regulators have the proper tools in response to the issue.

But others have seen trouble brewing as far back as 2020 (or earlier) when commercial banking assets were skyrocketing and banks were buying bonds when rates were low.