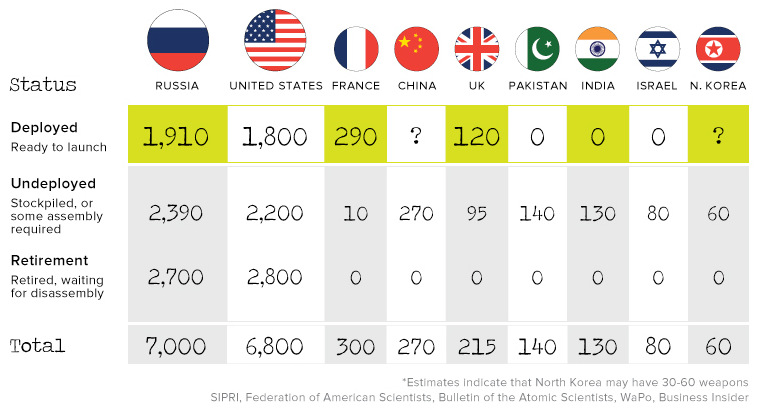

The U.S. nuclear program is comprised of a complex network of facilities and weaponry, and of course the actual warheads themselves. Let’s look at the location of warheads, how they’re deployed, and the costs associated with running and refurbishing an aging nuclear program. Let’s launch into the data.

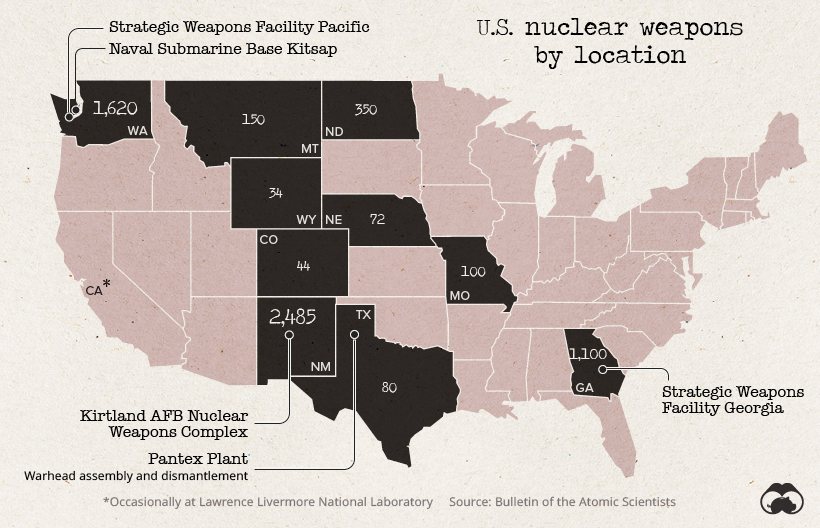

Nuclear Weapons Map

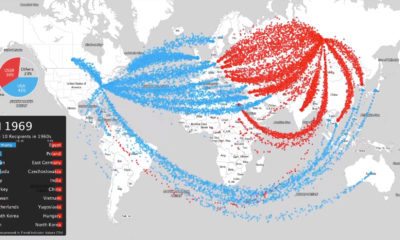

As of 2019, the U.S. Department of Defense maintained an estimated stockpile of 3,800 nuclear warheads for delivery by more than 800 ballistic missiles and aircraft. Roughly 1,300 warheads are actually deployed, while most of the remaining inventory is either held in reserve (as a hedge against “technical or geopolitical surprises”) or is destined to be dismantled. These weapons are thought to be stored across 11 U.S. states, with the vast majority residing in New Mexico, Washington, and Georgia.

Source Over 1,500 of the warheads in New Mexico are retired and are destined to be dismantled at the Pantex facility in Texas. The United States also maintains a small amount of nuclear inventory in and around Europe as well. Turkey’s Incirlik Air Base likely holds the biggest supply of warheads outside the U.S., and a few weapons are also located in storage vaults in Belgium, Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands.

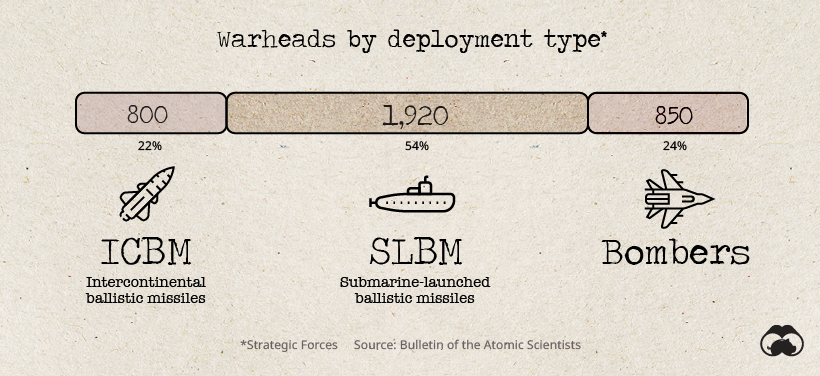

Deployment Data

Nuclear warheads, while devastatingly powerful, are nothing without a delivery mechanism. In simple terms, there are three primary methods for actually launching missiles: Silos, bombers, and submarines.

The most common deployment of nuclear weapons is under the sea. The U.S. Navy is thought to operate 14 ballistic missile submarines, with each carrying as many as 24 Trident II missiles. Missile silos are not as popular as they once were, but the U.S. Air Force still maintains 400 silo-based missiles, and another 50 are kept “warm” in the event of an emergency.

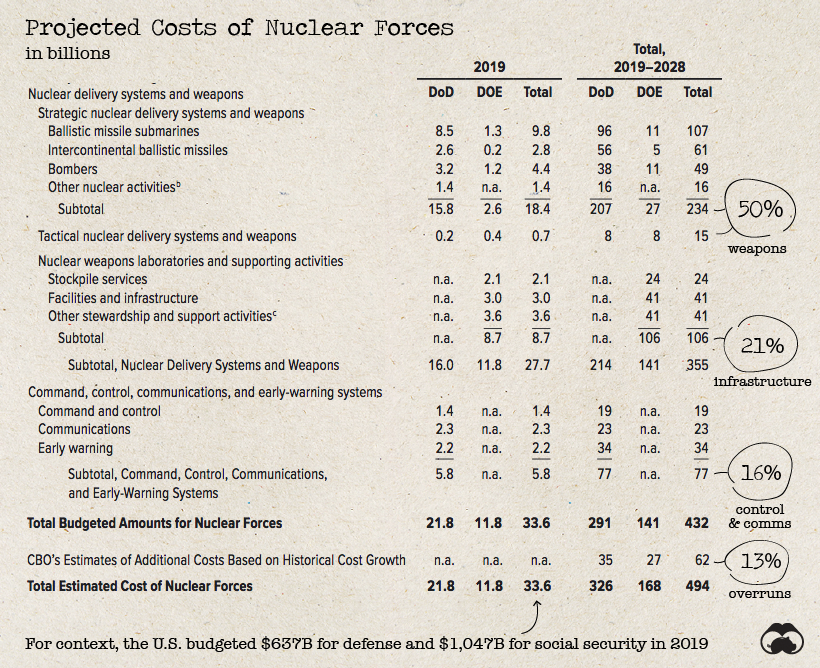

America’s Nuclear Weapons Budget

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is required to project the 10-year costs of nuclear forces every two years. Though much of the program is shrouded in secrecy, the budget below provides an overview of the costs of running America’s nuclear weapons arsenal.

Costs in the budget are split between the Department of Energy (DoE) and the Department of Defense (DoD), which handle different parts of the process. On one hand, the DoD takes care of the delivery systems for warheads. Those submarines, bombers, and missile silos spread around the country will add up to a projected $249 billion in costs over the next decade. Another large portion of the DoD budget accounts for operational aspects of the program, such as funding facilities, control, and early warning systems. On the other hand, the DoE is responsible for building and maintaining the actual warheads themselves. The U.S. stopped producing new warheads in the 1990s, but all that changed last year.

Back in the Bomb Business

Generally, we think of nuclear weapons stockpiles as a sunsetting resource, slowly being dismantled; however, since the treaty that ended the arms race collapsed in mid-2019, the flood gates may be opening once again. New warheads are reportedly rolling off the production line, and in the beginning of this year, Lockheed Martin was tapped by the U.S. Navy to manufacture low yield submarine-based nuclear missiles. The development of lower yield nuclear weapons appears to be a response to efforts by Russia to modernize their arsenal. – Nuclear Posture Review (2018) With this new weapons development, the U.S. is aiming to create “tailored response options” to any potential conflict. By eliminating the perceived advantages that adversaries may have, the U.S. is hoping to lower the likelihood of a nuclear conflict. Arms control advocates warn that new lower-yield warheads entering production will lower the threshold for a nuclear conflict. While advocates and critics of nuclear weapons debate the merits of new weapons, we appear to be entering a new era of weapons proliferation. on Both figures surpassed analyst expectations by a wide margin, and in January, the unemployment rate hit a 53-year low of 3.4%. With the recent release of February’s numbers, unemployment is now reported at a slightly higher 3.6%. A low unemployment rate is a classic sign of a strong economy. However, as this visualization shows, unemployment often reaches a cyclical low point right before a recession materializes.

Reasons for the Trend

In an interview regarding the January jobs data, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made a bold statement: While there’s nothing wrong with this assessment, the trend we’ve highlighted suggests that Yellen may need to backtrack in the near future. So why do recessions tend to begin after unemployment bottoms out?

The Economic Cycle

The economic cycle refers to the economy’s natural tendency to fluctuate between periods of growth and recession. This can be thought of similarly to the four seasons in a year. An economy expands (spring), reaches a peak (summer), begins to contract (fall), then hits a trough (winter). With this in mind, it’s reasonable to assume that a cyclical low in the unemployment rate (peak employment) is simply a sign that the economy has reached a high point.

Monetary Policy

During periods of low unemployment, employers may have a harder time finding workers. This forces them to offer higher wages, which can contribute to inflation. For context, consider the labor shortage that emerged following the COVID-19 pandemic. We can see that U.S. wage growth (represented by a three-month moving average) has climbed substantially, and has held above 6% since March 2022. The Federal Reserve, whose mandate is to ensure price stability, will take measures to prevent inflation from climbing too far. In practice, this involves raising interest rates, which makes borrowing more expensive and dampens economic activity. Companies are less likely to expand, reducing investment and cutting jobs. Consumers, on the other hand, reduce the amount of large purchases they make. Because of these reactions, some believe that aggressive rate hikes by the Fed can either cause a recession, or make them worse. This is supported by recent research, which found that since 1950, central banks have been unable to slow inflation without a recession occurring shortly after.

Politicians Clash With Economists

The Fed has raised interest rates at an unprecedented pace since March 2022 to combat high inflation. More recently, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell warned that interest rates could be raised even higher than originally expected if inflation continues above target. Senator Elizabeth Warren expressed concern that this would cost Americans their jobs, and ultimately, cause a recession. Powell remains committed to bringing down inflation, but with the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, some analysts believe there could be a pause coming in interest rate hikes. Editor’s note: just after publication of this article, it was confirmed that U.S. interest rates were hiked by 25 basis points (bps) by the Federal Reserve.