Today, China and India boast the largest populations, outpacing all others by a mile. The total populations of these two nations have been climbing for years, but India is moving at a faster clip. The big question is: When will India overtake China in population? This interactive chart by Our World in Data pulls past and projected population data from the United Nations, comparing the 300-year trajectory of China vs. India to answer this burning question.

China vs. India Population (1800-2100p)

In 1800, India’s population was at a modest 169 million. In contrast, the Chinese population was nearly double that with 322 million at the turn of the 19th century. It wasn’t until 1950 that the total populations of both countries started shooting up exponentially, and here’s where it starts to get interesting. China reached the 1 billion milestone in 1980, while India took a little longer to get there in 1997. And now, India is on target to overtake China’s total population in 2026, when both countries are expected to be at the 1.46 billion people mark. *Note: Absolute change numbers may not be exact due to rounding. Although the populations of both countries will begin contracting in the mid-21st century, India is expected to stay atop the global population leaderboard even by more moderate estimates.

China vs. India Demographics

While it appears that population growth in India is effectively mirroring that of China, there’s more to examine under the surface. What demographic trends lie behind the eventual contraction later this century? Let’s look at the two population pyramids to find out.

In China, growth has been underscored by a strict “one-child” policy, implemented in 1979. Even with the updated “two-child” policy in 2016, there’s no coming back from this decision—China is now contending with a rapidly aging population. It’s anticipated that over one-third of Chinese citizens will be 65 years old and above by 2050. Meanwhile in neighboring India, the workforce is just beginning to take off—65% of its population is currently aged 35 years and below. High rates of digital adoption are further compounding economic growth in the country, especially as the world becomes increasingly reliant on telecom and IT services.

China vs. India Economy

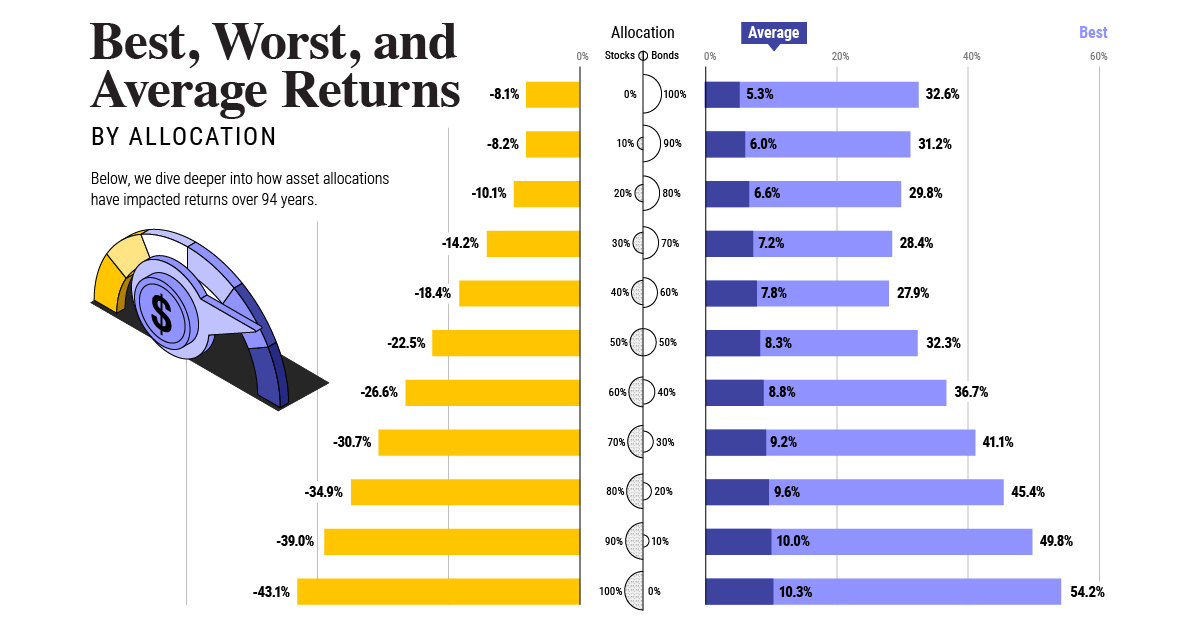

Another question this dramatic change begs is: at these rates of population change, can India’s GDP growth also surpass China’s in the next several decades? The short answer is likely a no, although both countries will still see immense GDP gains during this time. According to PwC, six of the seven largest economies in the world by 2050 will be today’s emerging markets—led by China and India in that order. While India isn’t likely to be the “next” China in terms of global GDP, it’s certainly giving it a fair fight as a potential rising superpower—and it all stems from the combined might of its growing population. on Last year, stock and bond returns tumbled after the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates at the fastest speed in 40 years. It was the first time in decades that both asset classes posted negative annual investment returns in tandem. Over four decades, this has happened 2.4% of the time across any 12-month rolling period. To look at how various stock and bond asset allocations have performed over history—and their broader correlations—the above graphic charts their best, worst, and average returns, using data from Vanguard.

How Has Asset Allocation Impacted Returns?

Based on data between 1926 and 2019, the table below looks at the spectrum of market returns of different asset allocations:

We can see that a portfolio made entirely of stocks returned 10.3% on average, the highest across all asset allocations. Of course, this came with wider return variance, hitting an annual low of -43% and a high of 54%.

A traditional 60/40 portfolio—which has lost its luster in recent years as low interest rates have led to lower bond returns—saw an average historical return of 8.8%. As interest rates have climbed in recent years, this may widen its appeal once again as bond returns may rise.

Meanwhile, a 100% bond portfolio averaged 5.3% in annual returns over the period. Bonds typically serve as a hedge against portfolio losses thanks to their typically negative historical correlation to stocks.

A Closer Look at Historical Correlations

To understand how 2022 was an outlier in terms of asset correlations we can look at the graphic below:

The last time stocks and bonds moved together in a negative direction was in 1969. At the time, inflation was accelerating and the Fed was hiking interest rates to cool rising costs. In fact, historically, when inflation surges, stocks and bonds have often moved in similar directions. Underscoring this divergence is real interest rate volatility. When real interest rates are a driving force in the market, as we have seen in the last year, it hurts both stock and bond returns. This is because higher interest rates can reduce the future cash flows of these investments. Adding another layer is the level of risk appetite among investors. When the economic outlook is uncertain and interest rate volatility is high, investors are more likely to take risk off their portfolios and demand higher returns for taking on higher risk. This can push down equity and bond prices. On the other hand, if the economic outlook is positive, investors may be willing to take on more risk, in turn potentially boosting equity prices.

Current Investment Returns in Context

Today, financial markets are seeing sharp swings as the ripple effects of higher interest rates are sinking in. For investors, historical data provides insight on long-term asset allocation trends. Over the last century, cycles of high interest rates have come and gone. Both equity and bond investment returns have been resilient for investors who stay the course.