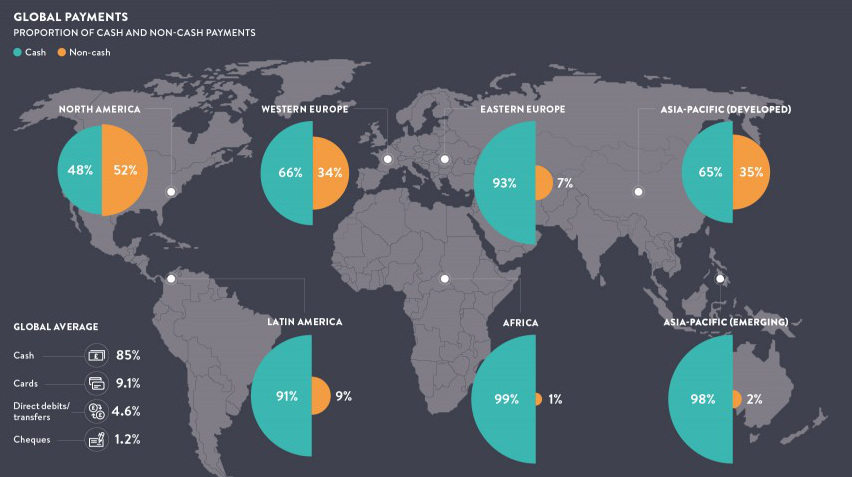

In some ways this is great news for consumers. The rise of mobile and electronic payments means faster, convenient, and more efficient purchases in most instances. New technologies are being built and improved to facilitate these transactions, and improving security is also a priority for many payment providers. However, there is also a darker side in the shift to a cashless society. Governments and central banks have a different rationale behind the elimination of cash transactions, and as a result, the so-called “war on cash” is on.

On the Path to a Cashless Society

The Federal Reserve estimates that there will be $616.9 billion in cashless transactions in 2016. That’s up from around $60 billion in 2010. Despite the magnitude of this overall shift, what is happening from country to country varies quite considerably. Consider the contradicting evidence between Sweden and Germany. In Sweden, about 59% of all consumer transactions are cashless, and hard currency makes up just 2% of the economy. Yet, across the Baltic Sea, Germans are far bigger proponents of modern cash. This should not be too surprising, considering that the German words for “debt” and “guilt” are the exact same. Within Germany, only 33% of consumer transactions are cashless, and there are only 0.06 credit cards in existence per person.

The Dark Side of Cashless

The shift to a cashless society is even gaining momentum in Germany, but it is not because of the willing adoption from the general public. According to Handelsblatt, a leading German business newspaper, a proposal to eliminate the €500 note while capping all cash transactions at €5,000 was made in February by the junior partner of the coalition government. Governments have been increasingly pushing for a cashless society. Ostensibly, by having a paper trail for all transactions, such a move would decrease crime, money laundering, and tax evasion. France’s finance minister recently stated that he would “fight against the use of cash and anonymity in the French economy” in order to prevent terrorism and other threats. Meanwhile, former Secretary of the Treasury and economist Larry Summers has called for scrapping the U.S. $100 bill – the most widely used currency note in the world.

“Smoother” Aggregate Demand?

It’s not simply an argument of the above government rationale versus that of privacy and anonymity. Perhaps the least talked-about implication of a cashless society is the way that it could potentially empower central banking to have more ammunition in “smoothing” out the way people save and spend money. By eliminating the prospect of cash savings, monetary policy options like negative interest rates would be much more effective if implemented. All money would presumably be stored under the same banking system umbrella, and even the most prudent savers could be taxed with negative rates to encourage consumer spending. While there are certainly benefits to using digital payments, our view is that going digital should be an individual consumer choice that can be based on personal benefits and drawbacks. People should have the voluntary choice of going plastic or using apps for payment, but they shouldn’t be pushed into either option unwillingly. Forced banishment of cash is a completely different thing, and we should be increasingly wary and suspicious of the real rationale behind such a scheme.

on Even while political regimes across these countries have changed over time, they’ve largely followed a few different types of governance. Today, every country can ultimately be classified into just nine broad forms of government systems. This map by Truman Du uses information from Wikipedia to map the government systems that rule the world today.

Countries By Type of Government

It’s important to note that this map charts government systems according to each country’s legal framework. Many countries have constitutions stating their de jure or legally recognized system of government, but their de facto or realized form of governance may be quite different. Here is a list of the stated government system of UN member states and observers as of January 2023: Let’s take a closer look at some of these systems.

Monarchies

Brought back into the spotlight after the death of Queen Elizabeth II of England in September 2022, this form of government has a single ruler. They carry titles from king and queen to sultan or emperor, and their government systems can be further divided into three modern types: constitutional, semi-constitutional, and absolute. A constitutional monarchy sees the monarch act as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, giving them little to no real power. For example, King Charles III is the head of 15 Commonwealth nations including Canada and Australia. However, each has their own head of government. On the other hand, a semi-constitutional monarchy lets the monarch or ruling royal family retain substantial political powers, as is the case in Jordan and Morocco. However, their monarchs still rule the country according to a democratic constitution and in concert with other institutions. Finally, an absolute monarchy is most like the monarchies of old, where the ruler has full power over governance, with modern examples including Saudi Arabia and Vatican City.

Republics

Unlike monarchies, the people hold the power in a republic government system, directly electing representatives to form government. Again, there are multiple types of modern republic governments: presidential, semi-presidential, and parliamentary. The presidential republic could be considered a direct progression from monarchies. This system has a strong and independent chief executive with extensive powers when it comes to domestic affairs and foreign policy. An example of this is the United States, where the President is both the head of state and the head of government. In a semi-presidential republic, the president is the head of state and has some executive powers that are independent of the legislature. However, the prime minister (or chancellor or equivalent title) is the head of government, responsible to the legislature along with the cabinet. Russia is a classic example of this type of government. The last type of republic system is parliamentary. In this system, the president is a figurehead, while the head of government holds real power and is validated by and accountable to the parliament. This type of system can be seen in Germany, Italy, and India and is akin to constitutional monarchies. It’s also important to point out that some parliamentary republic systems operate slightly differently. For example in South Africa, the president is both the head of state and government, but is elected directly by the legislature. This leaves them (and their ministries) potentially subject to parliamentary confidence.

One-Party State

Many of the systems above involve multiple political parties vying to rule and govern their respective countries. In a one-party state, also called a single-party state or single-party system, only one political party has the right to form government. All other political parties are either outlawed or only allowed limited participation in elections. In this system, a country’s head of state and head of government can be executive or ceremonial but political power is constitutionally linked to a single political movement. China is the most well-known example of this government system, with the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China ruling as the de facto leader since 1989.

Provisional

The final form of government is a provisional government formed as an interim or transitional government. In this system, an emergency governmental body is created to manage political transitions after the collapse of a government, or when a new state is formed. Often these evolve into fully constitutionalized systems, but sometimes they hold power for longer than expected. Some examples of countries that are considered provisional include Libya, Burkina Faso, and Chad.