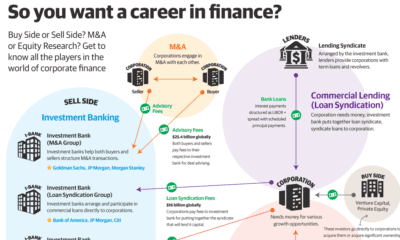

Maybe it’s because a struggling company got bought out and taken private, just as Toys “R” Us did in 2005 for $6.6 billion. Otherwise, it’s likely a mention of a major investment (or payout) that a PE firm scored through venture or growth capital. For example, after Airbnb had to postpone its original plans for a 2020 initial public offering (IPO) in light of the pandemic, the company raised more than $1 billion in PE funding to plan for a new listing later this year. Yet many people don’t fully understand the size and scope of private equity. To demonstrate the impact of PE, we break down the funds raised by the top 25 firms over the last five years.

How Private Equity Firms Operate

First, we need to differentiate between private equity and other forms of investment. A PE firm makes investments and provides financial backing to startups and non-public companies (or public companies that are being taken private). Each firm raises a PE fund by pooling capital from investors, which it then uses to carry out transactions such as leveraged buyouts, venture and growth capital, distressed investments, and mezzanine capital. Unlike other investment firms such as hedge funds, private equity firms take a direct role in managing their assets. In order to maximize value, that can mean asset stripping, lay-offs, and other significant restructuring. Traditionally, PE investments are held on a longer-term basis, with the goal of maximizing the target company’s value through an IPO, merger, recapitalization, or sale.

The List: The Most PE Funds Raised in Five Years

So which names should you know in private equity? Here are the largest 25 private equity firms by their five-year PE fundraising total over the last five years, with data on funds and investments from respective firms and Private Equity International. They include well-known private equity houses like The Blackstone Group and KKR (Kohlberg Kravis Roberts), as well as investment managers with private equity divisions like BlackRock. Most of the world’s top PE firms, including TPG Capital (which invested in Ducati Motorcycles, J. Crew, and Del Monte Foods) and Advent International (an early investor in Lululemon Athletica) are headquartered in the U.S. In fact, of the largest 25 private equity firms in the last five years, just four are headquartered in Europe (CVC, EQT, Cinven, and Permira) and one in Asia (Hillhouse). Another name that might be recognizable is Bain Capital, which was co-founded by Utah Senator and former Republican Presidential nominee Mitt Romney and found success with investments in AMC Theatres, Domino’s Pizza, and iHeartMedia.

Famous Private Equity Investments

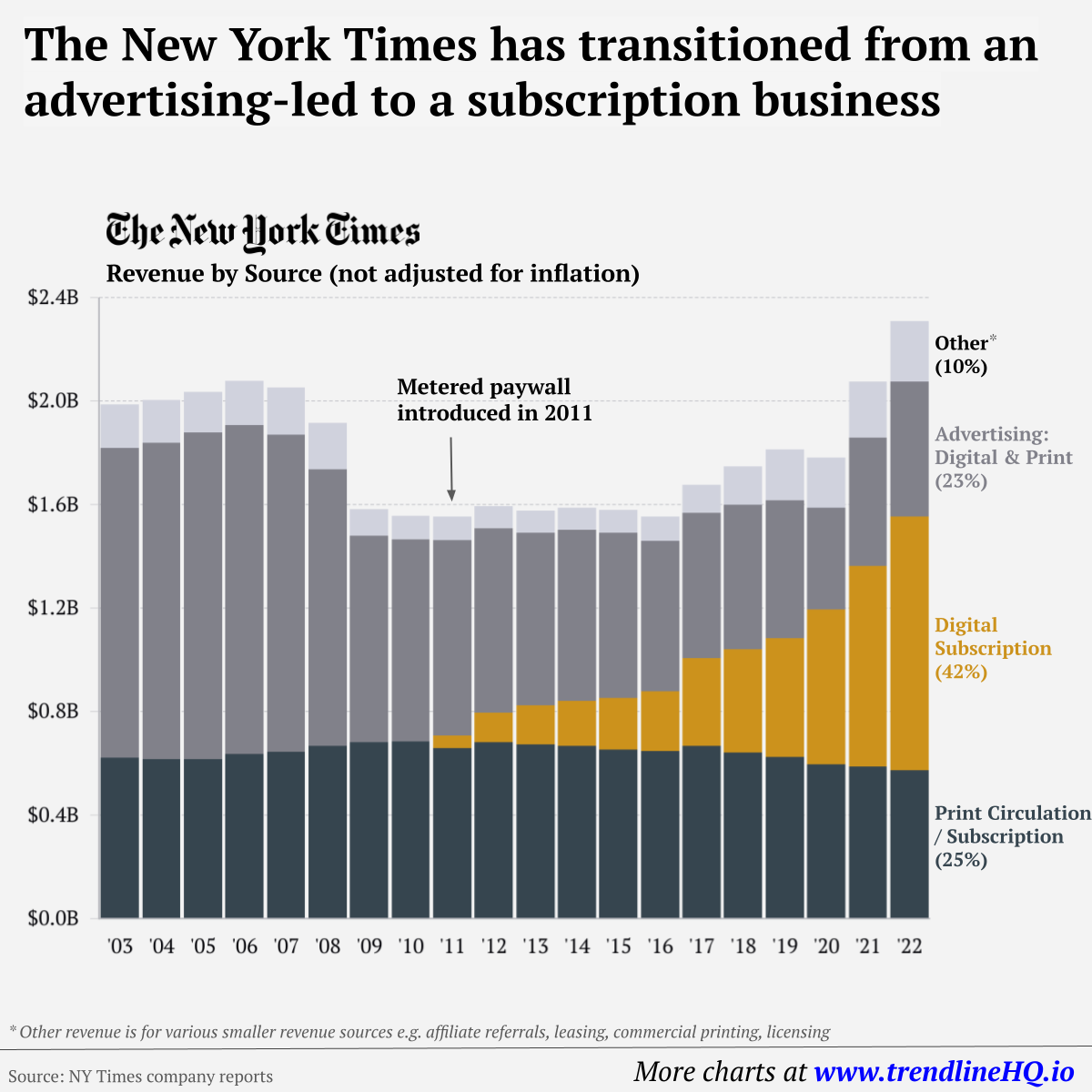

One of the most surprising things investors discover about private equity is how many large organizations have been funded through the PE world. More well-known investments include KKR’s $31.1 billion takeover of food and tobacco conglomerate RJR Nabisco in 1989, and Blackstone’s $26 billion buyout of Hilton Hotels Corporation in 2007. But other well-known companies have been funded, saved, or restructured through private equity. That list includes grocery chain Safeway, fast food chain Burger King, international racing operator Formula One Group, and hotel and casino company Caesars Entertainment (then called Harrah’s Entertainment). Many other notable investments could soon pay off for private equity. With IPOs back in season, tech companies like Airbnb and Epic Games are ripe for payouts. At the same time, restructuring companies like J. Crew and Chuck E Cheese’s always offers a chance to recapitalize. With the COVID-19 economic downturn resulting in newly distressed companies and potential takeover targets, expect the private equity world to be very active in the foreseeable future. on Similar to the the precedent set by the music industry, many news outlets have also been figuring out how to transition into a paid digital monetization model. Over the past decade or so, The New York Times (NY Times)—one of the world’s most iconic and widely read news organizations—has been transforming its revenue model to fit this trend. This chart from creator Trendline uses annual reports from the The New York Times Company to visualize how this seemingly simple transition helped the organization adapt to the digital era.

The New York Times’ Revenue Transition

The NY Times has always been one of the world’s most-widely circulated papers. Before the launch of its digital subscription model, it earned half its revenue from print and online advertisements. The rest of its income came in through circulation and other avenues including licensing, referrals, commercial printing, events, and so on. But after annual revenues dropped by more than $500 million from 2006 to 2010, something had to change. In 2011, the NY Times launched its new digital subscription model and put some of its online articles behind a paywall. It bet that consumers would be willing to pay for quality content. And while it faced a rocky start, with revenue through print circulation and advertising slowly dwindling and some consumers frustrated that once-available content was now paywalled, its income through digital subscriptions began to climb. After digital subscription revenues first launched in 2011, they totaled to $47 million of revenue in their first year. By 2022 they had climbed to $979 million and accounted for 42% of total revenue.

Why Are Readers Paying for News?

More than half of U.S. adults subscribe to the news in some format. That (perhaps surprisingly) includes around four out of 10 adults under the age of 35. One of the main reasons cited for this was the consistency of publications in covering a variety of news topics. And given the NY Times’ popularity, it’s no surprise that it recently ranked as the most popular news subscription.